In 2017, when Filterwatch first wrote about the progress of eGovernment in Iran, the Rouhani administration was preparing to unveil its eGovernment project, under the then-ICT Minister Mahmoud Vaezi. Now, almost four years and an ICT Minister later, we look at how, despite the slow progress of this ambitious project, it has taken some major strides, and in doing so, it has revealed a number of serious threats to the fundamental rights of Iranian citizens.

The origins of Iran’s eGovernment ambitions date back at least two decades, to the Khatami administration, which introduced the concept of eGovernment under the ‘The Development and Usage of ICT Technology in Iran’ national plan (commonly known by its Persian-language acronym TAKFA). However, following the 2005 election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, TAKFA and its targets were abandoned.

Despite TAKFA’s dissolution, eGovernment planning was not forgotten, and lived on within the Fifth and Sixth five-year National Development Plans. The Sixth Development Plan, which is set to conclude in the next Iranian calendar year (March 2020 – March 2021) included a number of targets, including the reduction of citizens’ physical attendance at government institutions by at least 12.5% annually. It also added the target of improving Iran’s global eGovernment ranking by 30 places (though it does not specify which ranking system this refers to), and mandated a minimum 7.5% annual increase in online trade.

Before we try to assess Iran’s progress on implementation, and the project’s implications for citizens’ rights online, let’s take a moment to clarify exactly what we mean by ‘eGovernment’, and to see whether Iran’s conception of it is in line with international standards.

Defining eGovernment

The United Nations defines eGovernment as:

“The use of ICTs to more effectively and efficiently deliver government services to citizens and businesses. It is the application of ICT in government operations, achieving public ends by digital means. The underlying principle of e-government, supported by an effective e-governance institutional framework, is to improve the internal workings of the public sector by reducing financial costs and transaction times so as to better integrate work flows and processes and enable effective resource utilization across the various public sector agencies aiming for sustainable solutions”.

The definition provided by Iranian officials and organisations is generally in line with these international definitions in terms of defining the programme’s objectives, however, the often intrusive implementation of eGovernment services is out of alignment in terms of its consideration for human rights standards. Problems arise through the state’s centralised management of access to services via mandatory biometric national ID cards, which contain large amounts of information for each citizen. Offline, the requirement to present national ID numbers in order to access government and public services is largely mandatory, and this carries over to accessing eGovernment services. While promoted by the government, and eGovernment’s advocates as a means to “reduce corruption, increase transparency, and accessibility,” it can also be used for restricting public access to government portals and essential services such as access to education or health care, as well as creating new means for surveillance and control.

eGovernment Revival Under Rouhani

With President Rouhani receiving criticism from conservative and hardliner opponents for his government’s lack of progress in implementing eGovernment during his first term (as well as scrutiny from Iran’s Supreme Leader), the pressure was on to deliver practical advances following his May 2017 re-election. Shortly after, the then ICT Minister Mahmoud Vaezi attended the unveiling of the ‘First Phase of eGovernment and Mobile Government’ in August 2017. During this ceremony, Vaezi announced the opening of a data centre dedicated to hosting eGovernment services, with a second set to open the following day. He also announced that 51 government organisations had launched 440 eGovernment services, (although he offered no further details about the nature of these services). Vaezi added that a second phase was to launch the following February with more eGovernment services to be announced then.

However, the second phase never materialised, as days later on 20 August 2017 Mohammad-Javad Azari Jahromi was installed as Rouhani’s new ICT Minister. Jahromi placed the eGovernment targets as set out by the Sixth Development Plan within his ICT Ministry’s agenda. However, it wasn’t until a year after Jahromi’s arrival that the ICT Ministry’s plans for eGovernment became more clear.

In May 2018 a number of national media outlets reported that the Cabinet had issued a list of ‘23 eGovernment Priority Projects’ to various executive organisations for implementation. The list cited the establishment of smart IDs, electronic signatures, an electronic tax and insurance system, and a comprehensive electronic health system, alongside other core eGovernment projects such as establishing a ‘Mobile eGovernment’ system.

Little was reported about the planning and progress of eGovernment following the Cabinet announcement. The ICT Ministry’s annual report published in August 2019 – focusing on Jahromi’s second year in office – made little mention of eGovernment achievements, focusing instead on domestic digital services. The biggest announcement was the claim that ‘over 450 million transactions’ had been conducted via eGovernment services in the previous year.

Despite this relative quiet, the fuel price protests and the subsequent internet shutdown of November 2019 demonstrated why eGovernment has progressively moved higher and higher up the government agenda: government services will need to be connected to the National Information Network (or NIN) in order to fully implement Iran’s localisation plans, and to ensure that essential services can remain online even in the event of an Internet shutdown. During the November shutdown, reports from inside the country claimed that some essential and government services such as hospitals and universities remained connected to the internet via the NIN. Nonetheless, the shutdown caused significant disruptions to the country.

Shortly after, in January 2020, a meeting of the Executive Council for Information Technology (ECIT) – one of the only Internet policy related councils that wasn’t abolished after the creation of the Supreme Council for Cyberspace (SCC) – was chaired by President Rouhani himself, marking the first time in 12 years that a sitting president chaired a meeting. In February, it was revealed that the Cabinet granted oversight of eGovernment to the ECIT, which was to periodically report to Majles (parliament), the SCC, and the Cabinet. The Council was also in charge of ensuring the streamlined exchange of data between various executive organizations. Since then, the Council has been meeting regularly with Rouhani as chair.

Where are We Now

Iran’s eGovernment services have significantly expanded since the start of the Rouhani administration. Various other strands of Iran’s ICT policies, such as the expansion of NIN infrastructure, and the outbreak of COVID-19 have also contributed towards eGovernment’s growth. Since 2016, Iran has moved from being ranked 106th by the UN’s eGovernment Index to 89th in 2020.

Like in many other countries, the COVID-19 pandemic has intensified the use of online tools and systems, especially an increased reliance on eGovernment services in order to keep the country functioning while limiting in-person contact. The Majles temporarily moved online, and more government services focused on developing their online capacities in order to reduce in-person contacts. Some court hearings attempted to move online due to pandemic, via a system provided by the Mobile Telecommunication Company of Iran (TCI). Digital solutions have also been considered in relation to containing the pandemic itself, with discussions held around the possibility of implementing a system linking positive COVID-19 results to citizen’s national IDs. COVID-positive citizens would be blocked from being able to purchase train, bus and plane tickets, and their movements would be restricted.

However, information from officials about the progress of eGovernment implementation remains patchy and inconsistent. In December 2020, ICT Minister Jahromi boasted that ‘around 80% of eGovernment services have been launched’. His claim comes after Rasht MP Jabar Kouchaki, stated in an interview in September 2020 that Jahromi’s report to the Parliamentary Budget Commission was ‘vague’ and ‘did not mention progress in relation to the Sixth Development Plan’.

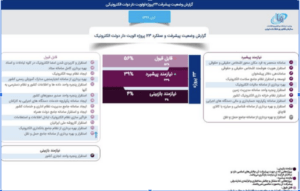

Infographic on eGovernment progress from E-Monitor

Prior to these statements, the ICT Ministry launched a new website in August 2020, designed to report progress on the 23 priority eGovernment projects, assigning them scores ranging from ‘acceptable’, to ‘in need of review’, and ‘in need of progress’. In November, it was confirmed that the website was hacked and defaced, after which the hackers attempted to sell the data scraped from the website online. Deputy ICT Minister Amir Nazemi claimed that the website did not contain confidential information.

The ECIT had also been experiencing tension during its meetings after the supervisory MP to the Council made comments on the priority of its agenda items. She stated that she had not been invited to any further meetings. The Secretary to the ECIT cited a lack of sufficient space for COVID-19-compliant social distancing as the reason for not inviting the MP to further meetings.

Meanwhile, the rollout of ‘smart’ biometric ID cards – which will act as the ‘keys’ to accessing Government services – has also come under scrutiny for delays, with the conclusion of their rollout now five years behind schedule (originally slated to run from 2012 to 2015). In November 2020 the Parliamentary Research Centre reported that out of the 62.5 million people eligible to receive their ID, 58 million had registered, and 48 million had actually received their cards. The report also stated that digital signature and authentication services have not been launched. The National Organisation for Civil Registration (NOCR) cited budgetary constraints and limitations caused by international sanctions for the slow rollout.

Despite these challenges, Iran’s eGovernment services have continued to slowly expand, and the government’s attention to the programme has grown. Iran’s draft budget for the next Iranian calendar year (March 2021 – March 2022) has dedicated 5,000,000,000,000 IRR (an estimated 118,750,740 USD) to eGovernment services via the ICT Ministry. The draft budget also allocated funds for the issuing of further national ID cards via the National Organisation for Civil Registration, but according to tech magazine Peivast, the funds allocated to ID rollout only makes up 0.5% of the organisation’s budget.

Worrying Trends and Emerging Threats

eGovernment schemes – if implemented correctly – can be hugely beneficial to citizens by making services more accessible, and public institutions more transparent. However, the Iranian government’s implementation poses major risks to citizens’ rights. As the project progresses, our understanding of these dangers is becoming ever more clear. Here are some of our concerns:

Limiting Access to Services and Expanding the Digital Divide: One of the most worrying threats presented by the national ID system is the exclusion of marginalised groups from receiving ID cards. One particularly stark example is that of Iran’s Baha’i religious minority community being denied national ID cards, a threat that has the potential to be extended to other minorities, including vulnerable refugees.

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Iranian NGO HAMI reported that Afghan refugee children (who lack national ID cards) were not able to access the new online learning platform Shaad. Shaad was the only state-sanctioned remote-learning service in operation during the closure of schools. Though according to Iran’s Education Ministry the issue has now been resolved, it is clear that the consequences – whether intentional or not – were significant for marginalised children.

Additionally, many parts of the country still suffer from chronic underinvestment in internet infrastructure, and while segments of the population will be unable to afford smart devices or internet services. Such digital divides can see lower income and otherwise marginalised populations simply left behind.

As more and more services go online, and the requirement for presenting a national ID card for identity verification becomes more common (or even mandatory) this can also exclude entire sections of society from having a legal identity. This could result in some citizens’ inability to obtain a passport, to access social services, and – as healthcare and health insurance provisions move online – potentially even to access essential health services. This is not unheard of elsewhere; glitches in India’s biometric welfare system, Aadhaar, and lack of access to ID cards has been described as the cause of death by starvation for some of India’s poorest citizens.

Facilitating ‘Layered Filtering’ Policies: In August 2019, the SCC passed a resolution titled: ‘Valid Identity Systems in Cyberspace’ which called for each individual to have a ‘valid ID’ for conducting online activities, which should be connected to an individual’s legal identity. While the details of how such a system will be implemented have not been revealed, it is very feasible that national IDs will play an important role in this system, by serving as the basis for an online ID system attached to national ID numbers. This ID system could help realise the government’s long-term ambitions for “layered filtering”, in which different levels of Internet access would be assigned to Iranian users via their IDs, based on their individual profile, status, and personal records.

Surveillance and Control: The integration of national ID cards into eGovernment services provides the state with large amounts of data on citizens. The centralisation of control over this data can leave it open to being misused for surveillance purposes. As in the case of linking COVID-19 positive cases to citizens, we can see that national IDs can be weaponised to restrict citizen’s ability to travel and access services, based on the government’s policies. This can even be true for private sector services, if they require ID verification via national ID cards.

This is particularly concerning as the planning and implementation has revealed little to no information on how the data is being kept secure, and how, as the data being shared with multiple organisations is being protected from misuse or unauthorised access. As we have seen, these systems are also prone to cyberattacks and the data they contain makes them more vulnerable. The lack of data protection laws in Iran, as well as a lack of focus and clarity around how citizen’s data is being collected, processed, and stored in a secure manner to prevent unauthorised access and data misuse for the purposes of surveillance currently poses a major threat to Iranian citizens.

The Way Forward

The pace of implementing eGovernment in Iran may have been sluggish, and may not have advanced to the level of other systems in place internationally, but nonetheless progress has been made in expanding its services over the last three years of Rouhani’s administration. This should not mean that Iran’s eGovernment plans should be dismissed or ignored, rather, it should be an area of focus for internet freedom activists and should be closely monitored and scrutinised.

Well-functioning, secure, and privacy-respecting eGovernment systems can deliver real benefits to citizens, in terms of service accessibility and transparency. However, its implementation in Iran should not come at a cost to Iranian citizens’ fundamental rights. Based on the Iranian government’s track record of pervasive surveillance and repression of free expression, the rollout of biometric smart ID cards and eGovernment services threatens to create yet another system of control which pose further threats to the human rights of Iranian citizens. Therefore, Iranian authorities must commit to improving privacy and security standards for their citizens by introducing robust data protection laws in line with international standards. Such measures are crucial in order to help prevent the misuse of personal and private data, and to provide an enabling environment for eGovernment systems to be implemented in a way that truly benefits all citizens – including those existing on the country’s social and economic margins.