Executive Summary

Research and polling by Filterban show that in the past year, more than 67 percent of internet users in Iran have been forced to download and use domestic messaging apps at least once. This poll, conducted from mid-to-late June 2023, reveals how the government employs various direct and indirect tactics to push citizens towards domestic platforms that are under its control.

The government has forced citizens to install domestic messaging apps by making them necessary for accessing various public services, such as health, education, and justice, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The government has effectively coerced citizens to use these messaging platforms by blocking other secure, popular, and international apps, and by offering lower rates for domestic internet bandwidth while restricting international bandwidth.

The astonishing figure of 67 percent indicates the government’s leap forward in fulfilling its goal, as laid out in the Seventh Development Plan, to dedicate more bandwidth to domestic than foreign internet traffic, with a 70:30 ratio, and to establish a national information network. Filterban has repeatedly warned, perhaps from the first indications, of the dangers of domestic messaging apps that enable the government’s digital totalitarianism, as part of its Internet Protection Plan and the creation of the national information network. This plan is the result of nearly two decades of internet policymaking by the authorities, who aim to establish a closed network, or intranet, where they can fully control the use of domestic platforms, the enforcement of surveillance and censorship policies, and the verification and regulation of users’ identities and behaviors.

Now that the government has finished building the technical infrastructure of this network, it is focusing on providing basic operational services and developing and expanding tools such as messaging apps, national email, and the like. Because of their infrastructural dependency on the government as well as the lack of robust privacy laws in Iran, these messaging apps are an ideal way for the government to surveil users’ content and communications.

The main obstacle for the national network plan has always been attracting users to the domestic platforms. Policymakers have worked to overcome this challenge with a variety of negative and positive policies: since 2018/2019, the Iranian government has actively supported the growth and variety of domestic messaging apps with financial and technical assistance.

Another prominent approach of the government to foster greater public acceptance of domestic messaging apps is widespread filtering of foreign platforms. The strategy was implemented in its entirety in the fall of 2022 when the remaining popular international platforms in Iran – Instagram and WhatsApp – were restricted in response to the countrywide uprising sparked by the death of Mahsa Jina Amini.

Alongside these new restrictions and the expansion of the digitalization of public services, we have witnessed an intensification of efforts to compel citizens to install and use domestic platforms for accessing these services. This coercion has been undertaken in various forms across a notable range: internal organizational communications of the staff of government bodies and state-governmental firms, communications of parents of school age children with school officials, access to credit and some banking services, smart police services, judicial services offices, communication of university students with educational groups, communication of retirees with pension funds, and even non-public transport services like freight shipping.

Despite this, the network growth and regular use of these messaging apps is surrounded by a cloud of uncertainty. Filterban’s polling shows that 72.8 percent of users use these apps only when necessary to complete administrative tasks, and these programs have no place in their daily communications.

On the other hand, though officials do not make exact statistics regarding users active on these messaging apps available, and details regarding the bandwidth dedicated to the traffic their traffic are classified, astonishing figures from the Ministry of Communications estimate that these apps have enjoyed a rate of user growth which has in some instances hit 900 percent in the last two years alone.

Though it seems domestic messaging apps have still not been able to replace foreign equivalents, our research shows that given all the restrictions that have been created for users – from internet speed to widespread filtering, high VPN prices, and a doubled tariff on foreign traffic – it is not unexpected that these apps may, in the near future, find a way into the day to day communications of users, even if in the past attracting such a volume of users to these platforms seemed unachievable.

This report aims to examine the unnatural growth of these messaging apps and the reasons why users do not trust them, which, above all else, are rooted in the dysfunction of these platforms, and to explain the hidden and overt motivations behind the government’s support for them.

These motivations have grounded the development of these platforms not in meeting demand, nor increasing services or developing more useful tools for users, but in the government’s insatiable appetite for extracting data and surveilling and controlling user’s content.

Collection Method

This report relies on various sources of data, such as:

- An investigation of more than 80 news items and reports from domestic media, including newspapers and news services,

- Filterban’s poll, with more than 400 respondents

- An investigation of prosecutorial documents obtained and leaked by hackers

- Local sources and field research

Research Challenges

Getting information in this field is very difficult. The security situation makes it risky and almost impossible to interview sources who use domestic messaging apps. The lack of transparency also prevents access to data such as traffic usage or active users. This makes it hard to verify unofficial statistics about these apps.

Beyond this, we lost certain details critical to this study because of their lack of importance for respondents. For instance: many participants in Filterban’s poll said they had been forced to install domestic messaging apps to receive administrative services, but they could not recall the task for which they did this, nor the app they used. A reason for this might be that most of them deleted the applications from their phones immediately after completing the administrative task.

Forcing Users to Install Domestic Messaging Apps: The How and Why

In today’s world, data has gone from being information about a topic to being a primary resource itself. Data can be likened to raw material extracted from the online activity of users. Just like petroleum, data is extracted, refined, and used in various ways. The emphasis on “various” owes to the fact that security aspects of the Iranian government’s widespread access to user data usually receive more attention than the economic consequences of its information monopoly. In any case, collecting, recording, and analyzing data requires a vast infrastructure. This is what internet policymakers in Iran have sought to create at the level of basic operational services in the NIN Plan.

This shows how important messaging platforms are for the Iranian government. Even though getting active users and growing naturally was always the hardest part of the plan, it was this key role that convinced some internet policy experts and digital rights activists to view the spread of these messaging apps as the inevitable fate of Iranian users.

Now, one year after the latest crackdown on foreign platforms, the Ministry of Communications reported a huge surge in the number of users of domestic messaging apps. According to its 20-month performance review in May/June 2023, these apps had grown by 400 to 900 percent, reaching 35 million users, in terms of monthly installation and use.

Though there are always serious doubts regarding the accuracy of these claims, Filterban’s polling shows that the government has been able to pressure citizens into installing these programs in light of its monopolistic nature and central role in their daily needs and affairs. It is crucial to evaluate the effectiveness of these measures, as this analysis could provide a more realistic and accurate perspective on potential future strategies to compel users to incorporate these apps into their daily routines.

Creating Accounts without Informing Individuals

An economic activist posted on his X (formerly Twitter) account on May 21, 2023, shortly after the Ministry of Communications had claimed huge numbers of users for domestic messaging apps, that he had discovered that two apps, Rubika and Eitaa, had created accounts for him without his consent, while he was dealing with a public service task.

Responding to the tweet, tens of other users, using their real names, confirmed that they had had similar experiences.

The creation of user accounts without people’s knowledge has precedent among domestic platforms, particularly Rubika. The marshaling of basic needs and necessary administrative communications to corral citizens into installing and disseminating these platforms is a new tactic, however.

Treatment Services

In April/May 2021, when Iran was among the 19 countries with the most coronavirus deaths and the outbreak was a national concern, the makers of Coviran Barakat, an Iranian vaccine, said that people could only sign up for the third phase of its trial through the iGap messaging app and a special phone line. The vaccine was made by a state institution under the Supreme Leader’s supervision.

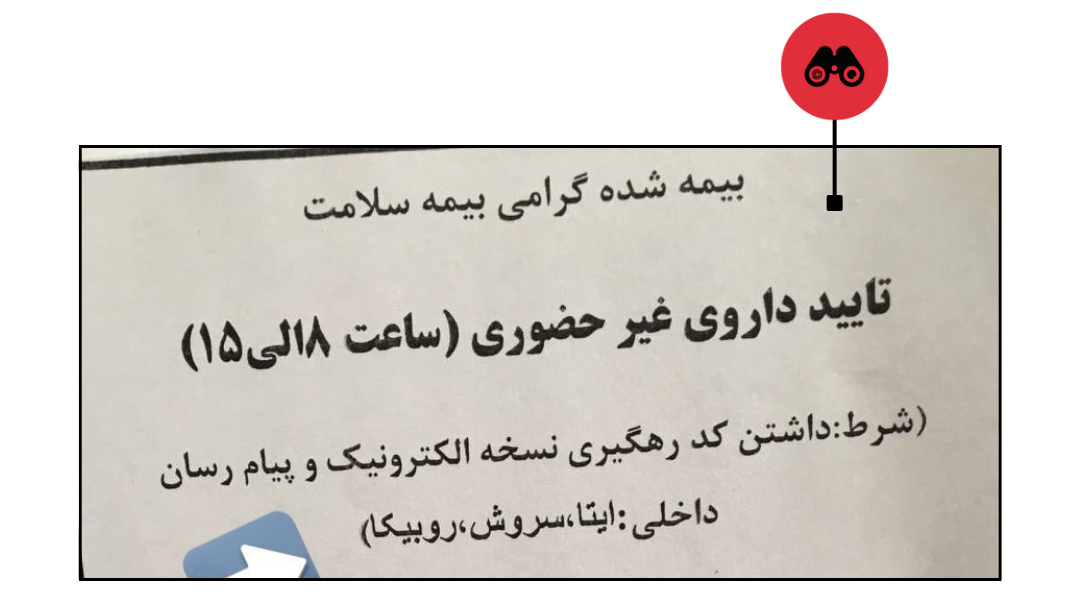

Other abuses of the health system to make people install these apps come in the form of requiring them for virtual treatment verification and some insurance companies.

Education

Filterban’s field reports confirm that use of these messaging apps in Iran’s educational system has become a norm. This includes the internal communications of educational staff, virtual groups of education officials and students’ families, news and update channels, schools and regional branches of the Ministry of Education, and virtual groups of teachers and students.

Many users in Filterban’s survey also said they had to use domestic messaging apps for education purposes, either for themselves or their children. This explains the huge increase in users for Eitaa, an app developed with funding from Qom University. According to the Communication Minister, this app grew from three million to 19 million users in just three months, from late September to late December.

The tactic is being rolled out in various ways at universities, as well. iGap and Eitaa were the two apps most named by poll respondents when they described the preconditions for registering and communicating with educational groups and professors.

Previously, iGap had acted alarmingly by forcing students of the Free Islamic University to download its application in order to receive an identity confirmation code.

Judicial Services

The electronic judicial services office is another of the service support systems conditioned on the installation of domestic messaging apps. In these offices, all online interactions and the sending and receiving of files are conducted by way of domestic messaging apps. Some users have reported that they had to use a specific app, Eitaa, for this purpose.

Despite all these arrangements, the government has not been very successful in getting active daily users for these platforms. It has also refused to share accurate statistics on users and bandwidth. The Communication Minister, Issah Zarehpour, called these numbers “minor messaging app information” and a trade secret in February/March 2023. Foreign messaging apps, on the other hand, publish these numbers every month.

Many reasons have been given for this. They include security issues and the “third tick,” an expression which refers to surveillance of user messages by a third party. In other words, people think that their messages and data are not safe from the security forces, and they do not trust domestic messaging apps. This is why they have a negative view of them.

The other issue, however, is that foreign messaging apps like WhatsApp and Telegram enjoy great popularity in Iran and enjoy a considerable superiority over domestic versions in terms of quality and features. The other side of the story is the dysfunction and poor quality of domestic messaging apps.

Dysfunction

Why do Iranian users not choose to use domestic apps voluntarily? Apart from mistrust, security issues, and privacy concerns, which are the main worries of users (and will be discussed later in this report), the poor performance of these apps may be another reason why they are not popular. Here are some examples of these problems.

Lack of Active Users

One of the main reasons why domestic messaging apps do not work well is that they have few users. There are many domestic messaging apps, but most of them are not chosen by users willingly. This means that there are not enough users on each platform. This prevents these apps from growing naturally and makes their millions of downloads meaningless.

Even in a hypothetical scenario where a network manages to stabilize itself within the country, it is difficult to imagine it expanding outside Iran’s borders. This raises an important question: why should Iranian users settle for messaging apps that isolate them from the rest of the world?

Predictably, these conditions have meant that most businesses have not adopted these platforms. Despite coordinated efforts and motives to encourage businesses to take up domestic platforms, statistics from the private sector show the futility of such policies. Aba’i Nayeb, head of Iran’s Commission on Technical Building Services and Room Engineering has referred to an issue of foreign entrepreneurs not having a general understanding of domestic messaging apps, which imposes limitations on economic activities. Additionally, efforts to force users to use domestic messaging apps are not only ineffective, but also give rise to a negative attitude among them.

Internet police officials have been trying to fix this weak point for a while, but they chose thea wrong solution as usual: enabling communication between domestic messaging apps. This feature made users even more suspicious, because of the lack of security protocols and infrastructural problems, especially in data center capacities.

Censorship

Censorship and internet surveillance are considered significant challenges for internet users in Iran. Using various tools, the government of Iran has always tried to increase its control over the internet and has shown a security response to users who publish content not aligned with its values in this space.

In recent years, particularly the last year, the government has worked to increase its command in the field of content production on social media by restricting foreign platforms, developing domestic platforms in unnatural ways, and forcing citizens to use domestic messaging apps with both punitive and incentivizing policies, and so has acted to head off information and opinions which it considers threatening to its moral and cultural existence by using authentication and identification of users as a means of pressure.

The scope of this “threatening content” has widened every day, and the cyberspace desired by the government tends more to homogenization every day. This government has exploited the inevitable interconnectedness of the online and real-world spaces to the benefit of applying its moral and intellectual framework in the private lives of citizens and has turned cyberspace into a powerful tool to enforce its rulings concerning them.

Domestic Platforms and the Hijab and Chastity Plan

In the most recent example of this approach, per Article 43 of the “Bill for the Support of the Family through Promoting the Culture of Chastity and the Hijab,” which was approved for a three-month trial period by the Majles on September 20, 2023, domestic platforms must block any content that promotes or advertises nudity, and they cannot publish any material that shows non-compliance with hijab or other dress codes.

All domestic platforms are, therefore, compelled to delete content with such subject matter in less than 12 hours after publication. This by itself might be confirmation of the strategic nature of domestic platforms, led by messaging apps, in advancing the political and cultural goals of the ruling system.

Complete and Total Access to Citizens’ Data

The extent of the access that police and judicial institutions have to the infrastructure and data of these platforms is clear from the fact that the bill also states that if a platform fails to censor the offending content, the relevant authorities will intervene and delete it within 24 hours.

In this context, Minister of Communications Issah Zarehpour told state news agency reporters in February/March 2022 that surveillance institutions were not permitted to access data, and that such access would only be possible with a special verdict of judges directly selected by the head of the judiciary, or in special cases authorized by the judiciary head.

However, these “special” cases that justify surveillance and censorship, which the Ministry of Communications and the government’s cultural supporters often compare to the content rules of international apps (such as those against pornographic or discriminatory content), have bare rigid, with constant red lines drawn around the most private of personal matters such as dress style and undesirable emojis, and even, as you will read below, economic issues like currency value and even criticism of internet speed.

By investigating the laws surrounding censorship and the process of their implementation, we can also begin to understand the fundamental motivations of internet policymakers’ persistent requests for international platforms to have a representative office within Iran as one of the preconditions of removing filters and authorizing their activity.

The Scope of Deletion and Censorship: Even You, Dear Friend

The scope of content deletion and censorship on domestic messaging apps is even greater than what has been discussed and has repeatedly struck even regime insiders.

On May 8, 2023, the Syria News Telegram Channel, which covers news regarding Iran’s role in Syria and the paramilitary “Shrine Defenders,” announced in a post that its account on the domestic messaging app Eitaa had received a “self-deprecation” warning for publishing a post criticizing internet speed.

Numerous instances of content censorship and deletion have been reported on Eitaa. This is the same messaging app which Morteza Agha Tehrani, head of the Majles’ Cultural Commission, said had been launched by five seminary students.

One instance was the deletion of the account of Mehdi Nasiri, the former manager of Keyhan, who said that he had been booted from the app on allegation of “norm violation and publishing inappropriate content.”

In another notable case, a report by the Principlist outlet Mashregh News made news after being deemed a violation simply for reporting currency values on its Eitaa channel.

It should be noted that this mitigation has occurred with content produced by individuals and groups in the circles closest to the state and forces aligned with the government. It is perhaps for just this reason that followers of the Syria News page, after repeatedly expressing their surprise at the censorship, wrote: “When they treat the Syria News channel, which is 100 percent at the service of the country, this way, God help the others.” This comment demonstrates the full range of dangers associated with publishing content on domestic platforms.

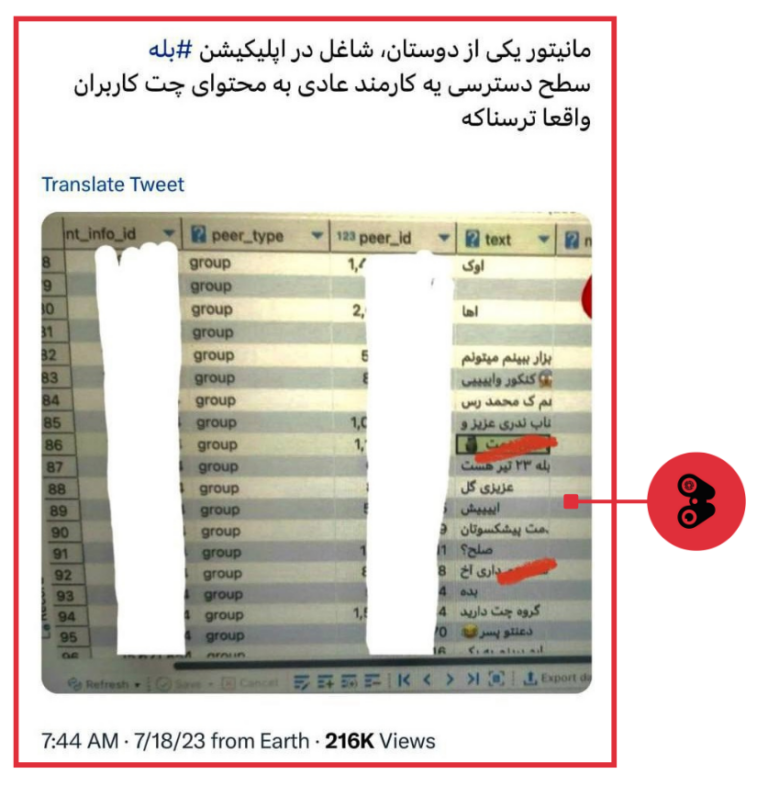

“Yes,” We Do Surveillance

In mid-July 2023, a Twitter user published an image of the monitoring page of a friend employed by the application Bale (“Yes” in Persian) and expressed surprise and regret at the level of the application’s employees’ access to user data.

This image shows that one users’ expletives in a group chat were targeted for deletion. It provoked many reactions and sparked new conversations about privacy violations on these platforms.

This development was followed by a response from Bale’s public relations. They stated in an announcement that the image pertained to a monitoring program meant to protect security and prevent fraud.

At any rate, this explanation was not convincing, and many digital rights experts and activists deemed it a justification for widespread censorship on Bale.

Rubika: Content Management with Censorship

Rubika, which debuted as a multipurpose application in 2015/2016, has become the Iranian domestic messaging app with the most users by receiving significant support and investment from the two main operators in the country, Hamrah-e Aval and IranCell. But this success has also come at a high price for the users’ freedom of expression.

In a June/July 2020 conversation with High Cyberspace Council member Rasoul Jalili, Rubika advisor Mohammad Rashidi indicated that the messaging app monitored 34 million pieces of content a day. “We must provide conditions where people can have confidence and use our platform, after that we can bring about behavior on a gentle slope, moderate their behavior, produce content, and change the culture” he explained.

These words indicate that Rubika and other domestic messaging apps supported by the government are acting to create a controlled and censored space. Using smart algorithms and surveillance teams, these messaging apps identify and eliminate “inappropriate” content based on the moral regime of the ruling faction. These are actions that clearly violate the freedom of speech and privacy of users.