In September 2014 President Hassan Rouhani’s government attempted to end the telecom monopoly by granting 3G and 4G service licenses to all providers, bringing mass access to fast mobile internet into reality, even in the most remote and economically deprived parts of the country, without the need for major capital investments in infrastructure, such as fiber optic internet.

The increased reach and speed of mobile internet sparked an interest from the authorities in the children’s use of the internet. Under pressure from conservative factions opposing internet freedoms, in 2015 the government ratified a plan drafted by the Communications Regulatory Authority (CRA) to design a SIM card for children, marking the beginning of a years-long effort by Iranian authorities to implement further restrictions on children’s access to the internet, a policy which is also part of the macro-planning for Iran’s information controls in the form of a tiered or layered access to the internet.

There are no exact figures on under-18 internet users in Iran. However, based on figures published by the Iran Statistical Center in 2017 and the Education Ministry’s Cultural Research Center in 2018 and the Attorney General’s Office in 2019, the number could be around 20 million users. In October 2021 Iran’s Statistical Center put the number of students aged 7-18 at about 15.7 million. It should be noted that according to the latest figures from inside Iran, there are more than 140 million mobile phone subscribers in Iran.

Between August 2016 and February 2022, four legislative instruments were enacted in connection with children’s use of mobile internet, one by the government and three by the Supreme Council for Cyberspace (SCC) which provided instructions to Internet Service Providers (ISP), as well as the Judiciary and security agencies.

The first resolution focused on using more typical censorship methods to block access to content deemed unsuitable for children. However, over time the authorities decided instead to focus on creating a separate network for children within the country’s domestic network known as the National Information Network (NIN).

According to policies, content accessible to children on the NIN are to be set according to: age, gender, and “physical traits such as disabilities,”. However, due to a lack of more specific or clear guidelines on how content should be sifted, so far ISPs have taken to interpreting these policies should look in practice themselves.

The implementation of policies to give restricted access to specific parts of the internet as approved by the government is part of the long-term policies of connection to giving tiered/layered access to the internet to different sections of society and the use of legal VPNs which is yet to be introduced.

The steps to “protect children” on the internet have gone as far as requiring ‘Safe Search‘ to be turned on as a default setting for children and adults on certain ISPs, enforcing the use of domestic search engines over international websites. This is yet another tactic to coerce users onto domestic online services, by directing them to use the ‘children’s internet ecosystem’ under the guise of protecting children online. Such measures are needed to help implement Iran’s internet policy to move users’ onto domestic content and services, which have not been popular with those inside Iran. In the near future, we are likely to see more measures to enforce migrations to domestic online services which run high risks for users which would be difficult to reverse.

Macro-Policies for Children’s Internet

Prior to initiating wider internet policies for children, the Communications Regulatory Authority (CRA) had taken steps to limit children’s online access. In fact, under pressure from hardliners, the government ratified specific guidelines before other institutions such as the SCC were involved.

In 2013, during Hassan Rouhani’s first term as President, hardliners raised alarm about the government’s plan to introduce faster and cheaper mobile internet access. On 21 August of the same year, Ruhollah Momen-Nasab who was the Head of Digital Media at the Ministry for Culture and Islamic Guidance during Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s Administration, said he had met with senior clerics in Qom who had expressed concern about faster internet. Days later, Momen-Nasab during a meeting of the “Revolutionary Cyberactivists” said: “3G internet amounts to a cultural chemical bomb in every mobile phone, giving enemies access to private information.” Momen-Nasab is said to be one of the main architects of the so-called “User Protection” Bill.

Eventually conservative protests led Grand Ayatollah Makkarem Shirazi, a hardliner loyal to the Islamic Republic to issue a fatwa on 25 August 2014, against using the faster internet, because it would allow “teenagers and even children to access content, movies and photos contrary to Islamic morals and beliefs.” Following on from the condemnation of higher internet speeds, on 28 April 2015, a group of MPs summoned the then ICT Minister Mahmoud Vaezi to Majles (Parliament) where he received a yellow-card warning about the issue.

Mobile Internet Regulations to Protect Children

Opposition to high internet speeds eventually reached a stage of forcing the government to act on two fronts: continue to develop 3G and 4G service, while bringing into force regulation in September 2016, known as “Mobile Internet Regulation to Protect Children and Teenagers.” This was the first step to create restrictions for children online and set up a special, limited, network for under-18 internet users, including the plan to create special SIM cards for children.

The most important aspects of the children’s SIM card include:

- For use by 3-18 year old

- Ban on the use of VPNs

- Using a specific ecosystem

- Access to only Persian language and Islamic-Shia content

- Allocating 15 percent of country’s traffic to children’s network

- Categorizing online content ‘appropriate’ to gender, age and disabilities

- More stringent punishments for illegal content

- To manage children’s content, creating a committee with representatives from a number of Ministries, Judiciary, state radio and television (IRIB), Police, the Islamic Development Organization, Shia seminary schools, the Basij, and the Supreme Council for Cyberspace (SCC).

- Mandatory ‘Safe Search’ for all users

- Ban on the use of Instagram, Google and Telegram.

Resolution on the Requirements for the National Information Network

The resolution on the ‘Requirements for the NIN’ was ratified by the SCC, the country’s top internet policymaking body, on 10 December 2016, aimed at “integrating views and guaranteeing network design coordination with upstream macro requirements” according to the resolution.

Other parts of the resolution state that ‘supporting the expansion of healthy, safe and useful virtual spaces, especially for children and families” is one of NIN’s primary objectives, The only other explanation on this topic is contained in a footnote which states: “the possibility of supporting the ranking and classification of content, services and tools for protecting children and families through white-lists etc.”

The “white-list” refers to information control tools used to restrict the internet in recent years – especially by the Information Technology Organization (ITO) – following the November 2019 internet shutdown. This “white-list” is a drastic method of internet censorship that allows for specific websites, apps and other online content to be accessed, while blocking everything else. The “black-list” method in contrast blocks specific websites, apps and other content while leaving other online content accessible.

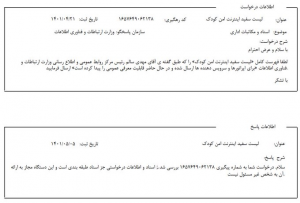

In July 2022, Amir Mojiry, an Iranian Twitter user made a ‘Freedom of Information Request’ to ask the ICT Ministry to provide details of the white- list, the response to which stated that the information was “confidential” and that “the requested document and information is confidential and we are not permitted to present it to unauthorized persons.”

[Images of Amir Mojiry’s request and the ministry’s response regarding the classified nature of the white-list’s “safe content” for children.]

National Information Network Macro[-Level] Plan and Architecture Resolution

The National Information Network Macro[-Level] Plan and Architecture’ resolution passed by the SCC on 15 September 2020 is said to be aimed at “strengthening, organizing and developing online content and user services.”

In the section on operational goals, the resolution mentions “the creation of an exclusive network” for children and teenagers and “increasing the share of useful content for the under-18 group to 15 percent of the country’s total national traffic.”

Article 6, 3.2.2 of NIN’s Macro Plan

This clause has many ambiguities:

- Considering the restrictions cited in the NIN Requirements Resolution in the form of a white-list, it can be deduced that the reference to an “exclusive network” is in fact a network limited to the white list.

- It is unclear what is meant by “secure and healthy content.” No definition has been provided

- It is unclear what is meant by 15 percent of the country’s total internet traffic. In 2017 the Iranian government allowed for domestic traffic to be charged at a lower rate compared to international traffic in violation of Net Neutrality principles. As a result, the domestic network is cheaper and faster than the external traffic. It is unclear if the 15 percent is referencing domestic traffic or international. It is unclear how the remaining 85 percent of the “total national traffic” would be accessed.

Resolution on the Protection of Children and Teenagers on the Internet

On 27 January 2022, a third resolution was passed by the SCC titled ‘Protection of Children and Teenagers on Internet’ which focused on children’s internet access.

According to the introduction, “the resolution on the Protection of Children and Teenagers on Internet has been ratified… in line with the National Information Network Macro[-Level] Plan and Architecture’ resolution with the goal of elevating the internet and protecting children and teenagers.”

The resolution is in line with previous censorship policies, this time in the name of protecting children. The definition of children was worded as “any person under 18 years of age in the territory under the Islamic Republic of Iran and who will be categorized by age within the framework of the resolution on the Fundamental Transformation of Education.”

Macro Policies

The section on macro policies has some important objectives:

- Classification of all content and services corresponding to the user’s age, gender, and physical and cultural characteristics, in order to ‘generate confidence and trust in the system,’ which would require the network’s content to go through several layers of filters and censors. Simply put, it appears that the policymakers want to generate separate content for various age groups, genders and cultural backgrounds.

- Increasing the capability of the Judiciary and the Police to effectively pursue criminals and online child sex offenders which points to judicial and security measures against content producers who break the law.

Creating ‘Safe Spaces’

One of the articles under the ‘Safe Spaces’ section summarizes the document’s overall objective:

“Creating infrastructure and basic services specifically to protect virtual environments, including ID verification, classified access, parental supervision, reporting/feedback, payment services, and regulations to encourage licensees to provide communication and information technology services to develop infrastructure and basic services, in a virtual environment to be created within six months by the ICT Ministry in cooperation with relevant institutions.”

The article points to ID verification and tiered access as two pillars of a layered internet. Creating such an environment would require a “legal VPN” program to authenticate user verification and then limit their users’ access to certain parts of the internet based on specific classifications.

A note under this clause states: “Holders of the license to provide fixed and mobile communication services must provide access and the ability to use the content and services available in these environments while implementing protected virtual environment(s) in their network.”

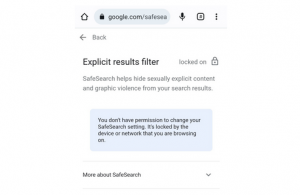

Since 12 July 2022, the state-owned Telecommunication Infrastructure Company (TIC) has been pointing all internet users in Iran to ‘Safe Search’ when trying to access Google, Bing or DuckDuckGo search engines.

Content Development and Categorized Services

This section focuses on policy methods and execution timetables. As an example, “all virtual content portals and service providers related to children and teenagers” have been required to develop their child-safe platforms within a year.

It should be noted that this plan was approved in February 2022 and, accordingly, by February 2023 all “virtual services” must be transferred to protected platforms. Already the implementation of mandatory use of SafeSearch is a sign that the plan is moving forward.

The one-year implementation goal has been explained in the section dedicated to “support and care” as well. Articles 4-11 state that:

“Requiring all platforms and online content and service providers to survey, protect data, categorize and partition content and special services for every age group from public services, and block exposure to advertisements, content and services harmful to these ages and also prevent the disclosure or unauthorized use of their information within a year.”

Authorized Institutions

According to the document, a committee would be formed under the National Center for Cyberspace (NCC) to draft operational models to manage and regulate a safe online environment for children. The committee would have representatives from Ministries of Islamic Guidance, Education, Intelligence, Labor, SAMAT (Industry, Mining and Trade), the Judiciary, state radio and television (IRIB), Police, the Islamic Propagation Organization, Shia seminaries in Qom, the Basij militia, the SCC (two reps), private sector (2 reps), a university professor chosen by the SCC Secretary, and the director of the NCC, who would be in charge of marco internet policies for children.

Mandatory ‘SafeSearch’

The dedicated children’s SIM card and other restrictions designed for children are not the only strategies employed by the Iranian authorities to control internet content under the guise of protecting the underage population.

On July 12, 2022, online users noted that their search engine requests were being automatically directed to Safe Search, which is designed for children. Initially this was happening only when trying to access Google on phones with SIM cards from the two main ISPs Hamrah-e-Avaland (MCI) and Irancell. But the auto redirect quickly spread to other search engines such as Bing and DuckDuckGo.

[Screenshot of Google’s SafeSearch mode]

A few days earlier, Communications Minister Eisa Zarepour appeared on state television to recount the virtues of ‘Safe Search’ as a tool for the protection of children on the internet and said: “Nowhere in the world have children been so exposed to such lack of protection on the internet as they have been in Iran. There are many online threats and governments have provided tools to families so that they won’t have to let go of their children in cyberspace. Safe experience, or safe search, is part of the literature created in Western countries. Even Google has a service called Safe Search and if you activate it, no matter what language is used in the search, none of the immoral content will be displayed. Public information about these services has been lacking.”

Later on July 20th, Zarepour claimed that the implementation of mandatory ‘Safe Search’ was a response to legitimate concerns: “Iranian families have been rightfully concerned about immodest and immoral content so we worked with communication operators to block access to them,” Zarepour said.

Of course he did not make it clear which authority and how such a decision was made, or what method was used to measure the level of Iranian families’ “concern” and how satisfied they are with mandatory Safe Search for children and adults alike.

Following Zarepour’s visit to Moscow on 24 July, the Russian search engine Yandex was unblocked but could only be accessed on Safe Search mode.

In other words, Iranian authorities are using tools developed by global tech companies for children to block the rest of the population access to legitimate information, a method which is unprecedented and all in the name of keeping children safe.