On 13 April this year, the Secretary to the Supreme Council for Cyberspace (SCC) Abolhassan Firouzabadi announced that a regulatory guidance for “Legal VPNs” has been finalised by the Committee for Determining Instances of Criminal Content (CDICC). He also added that the ICT Ministry will be in charge of deciding who will have access to legal VPNs. Since the text of the said regulation has not yet been made publicly available, this has raised confusion and concern among many Iranians.

This confusion is only natural, given that VPNs are most known to Iranians as circumvention tools that can bypass government filtering; the paradox of authorities implementing a hyper-restrictive filtering regime on the one hand, and legalising a market for bypassing it on the other is perplexing for many people.

However, the snippets of news that have emerged have been received with concern by Internet users inside Iran. Given the recent history of censorship and surveillance (and the CDICC’s role in implementing this) many have speculated that any new initiatives will seek to further restrict access to information, or to expand the state’s surveillance capacities.

This announcement – especially in absence of detail – may seem far-fetched, or unlikely to materialize. In this edition of Filterwatch, we will look at the historical context around the development of “Legal VPNs”, and in doing so will demonstrate that a form of “Legal VPN” distribution is already in place, and already undermining Iranians’ digital rights. This recent announcement however presents a real threat by expanding on these current practices.

We will also speculate what form these new “Legal VPNs” might take, and what these developments may mean for digital rights in the short- and long term.

We argue that Iran’s continuing work around “Legal VPNs” must be taken seriously as a core component of the state’s overarching strategy to localise the internet, and impose “layered filtering” to grant different levels of access to different social groups. These recent developments demonstrate again that new forms of information controls implemented in Iran may be challenging to detect, and could disrupt existing circumvention strategies in the medium-to-long term.

A Defeated Old Project?

The first trace of “Legal VPNs”, or state-sanctioned VPNs could be spotted in the final months of the Ahmadinejad administration. On 17 February 2013, Iran’s National Centre for Cyberspace (NCC) opened up registrations for receiving “Legal VPNs”. The online registration process was hosted at “vpn.ir”, and was open to organisations and individuals who held posts that “entitled” them to access to the state-backed

Registration was open for six days, and closed on 23 February. After this, officials announced that soon a separate registration process would begin for individuals to receive state-backed VPNs. However such a promise never fully materialised and on 16 June 2013 Mehdi Khodayi, the Head of Public Relations at the Telecommunication Infrastructure Company (TIC) announced that 70 organisations have already received their legal VPNs.

Only days later, on 22 June 2013 the then Head of the TIC, Mahmoud Khosravi announced that despite spending “millions”y, only 26 companies had registered – contradicting the earlier statistics. As a result, the TIC announced that the scheme was ending, and that “legal VPNs for individuals” would not be rolled out – the promise of opening registration to the general public never materialised. However, Iranian officials continued to insist that companies and organisations that needed to bypass internet filtering could apply for a licence, and receive permission to do so. However, since then, no attempt has been made to broaden access to these VPNs to the general public.

Current State of VPN Usage in Iran

According to Iran’s Cyber Police (FATA)’s own figures in October 2018 there were 10 to 12 millions VPN users in Iran – likely to be one of the highest percentages globally. There are three factors that have given rise to the prevalence of VPNs over the past decade:

- Firstly, the censorship of online content. Ten years of highly restrictive filtering practices – affecting a number of major social networking sites and communications apps, such as Twitter, Facebook and Telegram – has led to a huge surge in the usage of VPNs and other circumvention tools in Iran.

- Secondly, the vague legal status of VPNs. Currently, the widespread interpretation of existing law is that the use of VPNs is not unlawful – it is only their sale that is perceived to be punishable.

- The third factor is the widespread availability of VPNs and circumvention tools. Since the 2009 post-election protests, the digital rights community have produced a wide range of VPNs and anti-censorship tools, which have been made available to Iranians for free. Millions of Iranians use these tools on a daily basis to access the internet. As well as these free tools, there is a huge market of commercial VPNs which are sold in Iran, many of which are hosted inside the country.

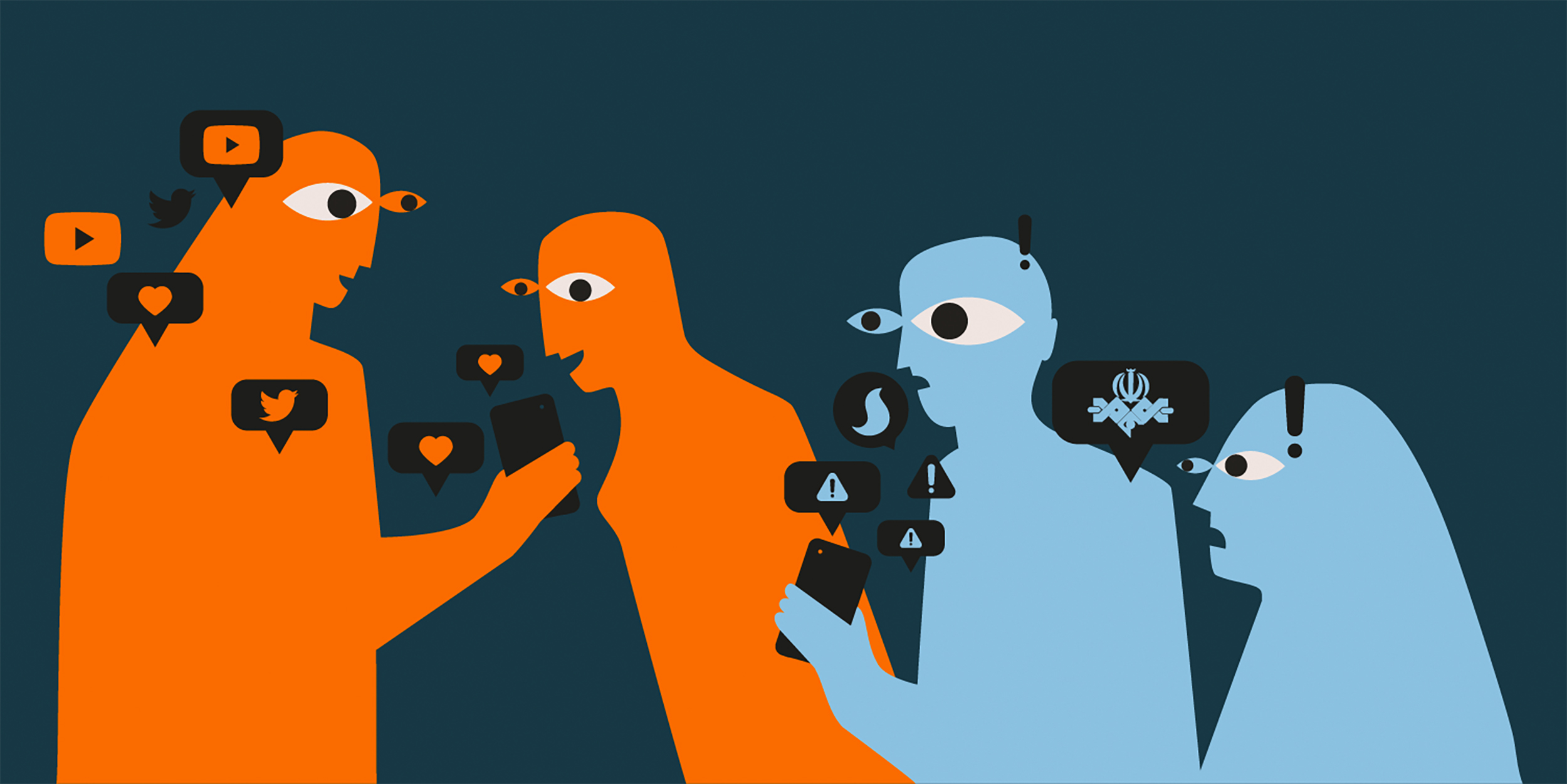

While widespread usage of VPNs is to be welcomed especially for privacy and security reasons, despite the best efforts and warnings of digital rights activists, a huge number of Iranian users still use VPNs which are bought, sold and hosted within Iran. A number of questions about their safety and security have been raised over the years, with many warning that these VPNs could have connections to the Iranian authorities and security forces.

Although the Iranian authorities have never confirmed their involvement in regulating the sale of VPNs in Iran, some recent comments in the Majles by ICT Minister Mohammad-Javad Azari Jahromi have partially confirmed suspicions that the current VPN market in Iran only exists with the tacit permission of some authorities.

In September 2019, When the Iranian Parliament questioned Azari Jahromi about the state of Iran’s Internet, he spoke about the circumvention tools “mafia” in Iran, claiming that it is “impossible” that authorities do not know who is behind the network of VPN sellers in Iran, and hinting at the lack of interventions from both FATA and the Judiciary.

Azari Jahromi is correct that the current VPN market in Iran leaves both buyers’ and sellers’ identities exposed to authorities. The CDICC even has a section on its website asking people to record the financial information (such as bank transfer details) of VPN sellers inside the country.

Although it is repeated time and time again that the sale of VPNs is illegal, these domestic vendors continue to freely sell their products using different parts of the Iranian online financial system, including prepaid cards. This practice exposes the identity of sellers and buyers to the authorities, as the information for the buyers and sellers are recorded, and financial intermediaries in Iran charge transaction fees to make the transactions possible.

Even in October 2019, Deputy ICT Minister and the Head of the TIC Hamid Fatahi stated that the ICT Ministry had submitted a list of VPN vendors to the judiciary. He also claimed that other state organisations in Iran have submitted a list of 200-300 VPN sellers to the Iranian judiciary.

As well as these commercial domestic VPNs, there are other VPNs and circumvention tools which are openly sanctioned by the authorities and are currently in use in Iran. In recent years a number of service providers in Iran have offered circumvention tools to Iranians to help them bypass US-imposed sanctions, and to access sites closed to Iranians.

In August the ISP Shatel announced that it had added a new service for its customers allowing them access to a large number of sites which – according to Shatel – do not provide services to Iranian IP addresses. According to Shatel, these sites,such as Adobe, Intel, and Oracle closed their services to Iranians, citing US-imposed sanctions.

This is not the first time that state-backed services have provided access to sanctioned websites. Shecan has been operating in Iran for some time now, offering a circumvention tool for any Iranian Internet user to help them bypass sanctions. Both Shecan and Shatel are otherwise fully in line with Iran’s filtering regime, denying access to sites filtered by the Iranian authorities. The availability of these tools tells us that there is no need for a new regulatory framework to offer VPNs to bypass sanctions.

The current approach to VPNs by the Iranian authorities is driven by two motives; firstly, financial gain, and secondly, the facilitation of surveillance and censorship practices. Exploring how Iran is currently benefiting from the VPN market and other domestic VPNs gives us an insight into why Iran may be seeking to further expand and formalise the sale of “legal VPNs”.

As the current market makes use of Iran’s online banking system, Iranian authorities benefit from every transaction. But perhaps more substantially, they benefit financially from Iran’s lack of net neutrality, which means that internet browsing via VPNs costs users significantly more than non-VPN-based activity.

Surveillance remains the most concerning motive, however. Whereas a secure VPN significantly improves the security of Iranian internet users, an unsafe VPN service can significantly increase the risk of surveillance by those who have access to the VPN’s backend. Given that Iranian officials have stated on a number of occasions that they have drawn up a list of VPN vendors inside Iran (and given that they appear to operate without any legal consequences), it is entirely possible that the state security services may have approached the VPN vendors seeking cooperation, and access to their users’ data. Even if such an arrangement has not taken place, Iranian authorities may benefit from users’ fears about domestic VPNs’ dangers, inspiring user self-censorship.

Layered Filtering and “Legal VPNs”

As noted, there are currently no public documents available describing the current proposed scheme for regulating “Legal VPNs”. However in an interview on 14 April this year, former Deputy for Cyberspace Affairs at the Public Prosecutor’s Office Javad Javidnia stated that the scheme’s goal is to provide different groups of society – such as students or journalists – with differing levels of access to currently-filtered websites. Firouzabadi’s comments from 11 November 2019 also confirms Javidnia’s recent comment: in November last year Firouzabadi said that the CDICC had been asked to set different levels of access privilege for Iranian users, and promised that Iranian operators would soon create legal domestic VPNs.

Iranian authorities are aware of the financial benefits and surveillance opportunities that regulating VPN vendors might bring. However, it can be argued that they are already enjoying a number of those benefits. In the absence of details, we can only speculate about the direction of the new scheme, the motives behind it, and the dangers it might pose to digital rights. We believe that the policies which are currently being developed by CDICC must be viewed as part of a wider plan for the implementation of “layered filtering”, a scheme supported and promoted by ICT Minister Azari Jahromi and the SCC. In the past we have written about the Layered filtering in Iran which seeks to grant different social groups in Iran different sets of privileges to bypass censorship regime.

Many Iranian policy makers have been arguing for the filtering of Instagram in Iran in recent months. It’s opponents have argued that the filtering of Telegram may lead to further growth of

VPN use in Iran. It is likely that some policy makers at the ICT Ministry, CDICC and SCC view layered filtering and the “Legal VPN” scheme as solutions to this problem.

The new “Legal VPN” framework will likely enable Iranian authorities to expand on existing schemes (such as VPNs for selected journalists), and to grant certain (selected) groups unfiltered (but highly monitored) access to the internet.

It remains unclear how long it will take Iranian authorities to introduce the “Legal VPN” scheme, if it is to materialise. The scheme must be opposed by digital rights activists and internet users inside Iran. In addition, Iranian authorities must cease their battle against VPNs provided by digital rights activists outside the country. This is particularly important given recent developments related to data security which have highlighted the fundamental insecurity of the internet and user data inside Iran.