The everyday experience of the internet in Iran is restricted through platform and content filtering, throttling, surveillance, and the monitoring of online behaviors. While these are common and long-running forms of information control and censorship, an increase in the use of Internet shutdowns by state authorities is rapidly becoming a major source of anxiety for Iranian internet users.

Iran experienced its first nationwide Internet shutdown during protests against fuel price increases in November 2019, when government authorities imposed a near total internet shutdown for at least a week to provide cover for a violent crackdown against protestors. While we have not observed any nationwide shutdowns in Iran since then, this is due to a shift in information control tactics, rather than a lifting of restrictions.

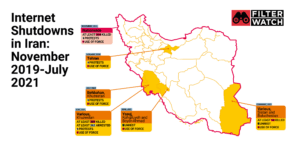

In fact, we have seen a steady increase in the number of internet shutdowns implemented at the local level, in order to contain protests, and limit information emerging about other forms of unrest. Since November 2019, there have been at least five instances of localised Internet shutdowns across Iran, with the most recent imposed in July 2021 following the outbreak of protests about water shortages in Khuzestan province.

So what is changing about Iran’s information controls strategy, and what role are internet shutdowns playing in it? In this piece, Filterwatch looks at the growing trend of localised internet shutdowns in Iran, and some of their common features. Based on a number of case studies, we’ll argue that these types of shutdowns – though perhaps not as dramatic as nationwide blackouts – can be just as deadly, and dangerous. We will also explore how changes in the decision-making processes behind shutdowns could risk further normalising them, and making local shutdowns more and more frequent.

What is an Internet Shutdown?

Internet shutdowns take a number of forms, and so it can be tricky to pin down exactly what we mean when we talk about shutdowns. The anti-shutdowns #KeepItOn campaign defines an internet shutdown as “an intentional disruption of internet or electronic communications, rendering them inaccessible or effectively unusable, for a specific population or within a location, often to exert control over the flow of information.” Such disruptions could encompass targeted throttling or “slowdowns”, local outages, or nationwide internet blackouts – all of which we have seen in operation in Iran.

According to Clement Voule, UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and Association, Internet shutdowns are “a growing global phenomenon,” being imposed by an increasing number of governments during mass demonstrations, which have “increased in length, scale, and sophistication.”

Internet shutdowns violate people’s rights to freedom of expression and assembly, and critically undermine press freedoms by restricting the free flow of information, often during periods of crisis. Internet shutdowns are often deployed by authoritarian governments during politically sensitive periods, such as during protests or elections, in order to create information blackouts and disrupt efforts to organise protests and demonstrations, and to cover up heavy handed crackdown of protests. Internet shutdowns are a global challenge, but their implementation and impacts in Iran have been particularly corrosive to the fundamental rights of Iranians.

Internet Shutdowns in Iran

As mentioned, Internet shutdowns can be implemented in a number of different ways. This includes nationwide shutdowns, localised shutdowns covering a specific geographical area, or disruptions to communication and social media platforms. These disruptions and disconnections can impact either mobile or fixed-line connections, or both.

So far, in Iran, we have observed several variations of shutdowns being used, including one nationwide shutdown in November 2019, and at least five local Internet shutdowns since, implemented across a number of different provinces to date, which are detailed below.

On 15 November 2019 a sudden announcement of fuel price increases sparked protests which quickly spread across the country. By 16 November, Internet connectivity began to drop in a number of provinces, starting first in regions showing signs of unrest. Eventually, access to the global Internet was restricted across the entire country, affecting both mobile and fixed internet connections. Small streams of connectivity remained in place, likely for use by government services.

Reports from local news stated that some universities, banks, and hospitals remained online for at least part of the the duration of the nationwide shutdown. Significantly, as the shutdown went on, observers noted that domestic services hosted via the National Information Network (NIN) remained available for some of the duration of the shutdown. This included Iranian ride-hailing apps, messaging apps, and shopping platforms (although connectivity was reported to be somewhat patchy). This led to one Iranian news outlet calling the Internet shutdown a “relatively successful experiment for Iran’s ‘National Internet’.”

During the shutdown, protestors were met by a violent crackdown from state security forces. According to a September 2020 report by Amnesty International, more than 7,000 people were arrested in connection with the protests, and at least 304 people were killed by security forces, although the true figure could be even higher. Of the reported figures, more than 220 killings took place within 48 hours of the internet shutdown on 16 November, according to Amnesty International.

A week later, as the protests died down, Internet connectivity was restored incrementally across the country. But in some areas where protests and civil unrest continued – such as in Sistan and Baluchestan – the shutdown continued for longer, which authorities attributed to “security issues.” The fact that both the shutdown and the reconnection took place incrementally evidenced that there was no central “kill switch”. Instead, ISPs were ordered to cut users’ access to the internet, which was implemented by each ISP individually.

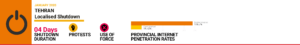

Following the tragic shooting down of Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752 by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) – killing all 176 people on board – a number of protests and demonstrations took place in Iran. On 11 January Filterwatch observed significant levels of packet droppage on WhatsApp, one of the few international platforms that is not blocked in Iran.

Following the disruptions to WhatsApp, at around 17:20 local time on 12 January, MCI and Irancell services were disrupted — mainly around Azadi Square and other areas that saw significant numbers of protestors on the streets. Based on data collected from three different data centers across Iran, MCI was completely disconnected from the global internet. The next day on 13 January, mobile data services remained suspended in some parts of Tehran, including continued disruptions around Azadi Square, where some demonstrations were taking place. On 14 January Filterwatch observed a total shutdown lasting around 15 minutes starting at 17:19 local time in Tehran.

On July 16, in response to a protest in the city of Behbahan in Khuzestan Province, Iranian security forces fired tear gas to disperse protesters. The protest started at around 8pm local time on 16 July. Around 45 minutes later, users in the neighborhoods where protests took place found that their mobile internet connections had been cut off. Users in this region are highly dependent on mobile internet services for access: according to Iran’s Communication Regulatory Authority (CRA) mobile internet penetration rates in the province sit at 105.97%, compared to fixed broadband rates of 7.97%.

Unfortunately, no network measurement tools were able to show any sign of this shutdown. Filterwatch was able to confirm this shutdown through field research, and through information provided by a third-party technology company.

Internet connectivity was restored by midnight, after the protest had concluded. Based on reports from sources based in Behbahan, the internet was fully functional for users located just 2km away from the protest site at the time of the protest. Iranian officials did not acknowledge the localised internet shutdown in Behbahan.

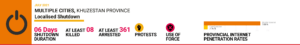

In February 2021, reports emerged of clashes between IRGC forces and fuel traders in the city of Saravan, in Sistan and Baluchestan province near the border with Pakistan. According to information received by the Baloch Activists Campaign (BAC), IRGC forces opened fire on fuel traders during ongoing clashes. The incident sparked protests in the city of Saravan, where protestors were reportedly met with tear gas, and a number of people were arrested.

By 24 February protests in Saravan escalated, and reports emerged of authorities using force against protestors. At the same time mobile internet connections were severely disrupted and eventually cut off entirely on Iran’s major mobile operators, including the Mobile Telecommunication Company of Iran (MCI), Irancell, and Rightel. These shutdowns were observed in the cities of Zahedan, Khash, Saravan, Iranshahr, and Zabol. Mobile internet connectivity continued to be disrupted until at least 26 February (despite some sporadic reports of connectivity) while fixed broadband connections appeared to be unaffected. However, given that, according to CRA statistics, 95% of the population rely on mobile networks for internet access, the disruption of mobile internet in practice had the effect of imposing a total internet shutdown across much of the province.

According to a statement by Amnesty International published in March 2021 at least 10 people were documented as being killed during the clashes, and dozens more were injured or arrested, though actual figures could be higher.

On June 20, mobile data was cut off for almost the entire day via Irancell and MCI in Yasuj, the provincial capital of Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province. The localised shutdown was in response to a clash between two local tribes in relation to the results of local city council elections. The internet was partially restored on June 21 at around 16:00 local time, and by June 22 it had been fully restored.

According to local sources, the Tamoradi and Tirtaji tribes, which both had candidates standing in the city council election, clashed in the streets to protest the election results in support of their own candidate. As a result, police opened fire on protesters, wounding a number of people.

Just like we saw in the last localised mobile internet shutdown in Sistan and Baluchestan, no network measurement tools were able to identify this shutdown as it took place.

On the evening of 15 July, reports emerged of protests breaking out in a number of cities across the southwestern Province of Khuzestan, with footage of the protests circulating on social media the next day. The protests were sparked by a severe water crisis which has prevented many of the province’s inhabitants from being able to reliably access clean drinking water or access to water for agricultural purposes.

On 18 July, intermittent disruptions to mobile internet access in Khuzestan province were confirmed. As noted earlier, according to the CRA, mobile internet penetration rates in the province sit at 105.97%, compared to fixed broadband penetration rates of 7.97%. As a result, disruptions to mobile internet services have the effect of imposing a near-total internet shutdown in the province. The disruptions were imposed specifically on those areas experiencing protests and unrest, and for varying periods of time to allow security forces to disperse gathering crowds.

The Internet shutdown continued until at least 23 July. In some areas, domestic services were available via the NIN. Specific platforms, such as WhatsApp also experienced traffic throttling, causing significant delays in users’ ability to send images and videos.

As protests continued in Khuzestan, they also spread to other parts of the country, accompanied with further internet disruptions. At least eight people were killed during this period of unrest, according to a statement from Amnesty International on 23 July 2021. The Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA) also reported that at least 361 people were arrested according to a statement on 5 August 2021, though actual figures may be much higher.

Who Orders the Internet Shutdowns in Iran?

As the November 2019 shutdown went on, one question was continually raised: “who ordered the Internet shutdown?” At the time, we lacked real clarity on this – many of the key decisions were taken behind closed doors, and were shrouded in secrecy. It was not until the third day of the internet shutdown that then-ICT Minister, Mohammad-Javad Azari Jahromi acknowledged the shutdowns, and denied any responsibility for the decision by his ministry, claiming that he himself “did not have access to the internet.”

Later in November Jahromi stated that the internet shutdown was ordered by the National Security Council (NSC) (Persian: شورای امنیت کشور or شاک ) which ordered the ISPs to disconnect users from the Internet.The body is headed by the Interior Minister, and its membership includes representatives from the ICT Ministry, Ministry of Intelligence, the IRGC, and the Armed Forces, among others.

In the aftermath of the November shutdown, in December 2019 Jahromi announced working on a bill to formalise and codify the internet shutdown process in Iran. However, according to a source close to the ICT Ministry who spoke to Filterwatch on the condition of anonymity, this bill was never introduced in the Majles due to pushback from security agencies, and the NSC. Instead, the bill became a top-secret resolution of the NSC.

According to Filterwatch’s sources, the resolution sets out the process for ordering and implementing internet shutdowns in Iran. This may have been initiated following the November 2019 protests, when Iranian authorities envisioned more frequent impositions of internet shutdowns in order to repress and silence protests. Based on information passed on to Filterwatch, province-level internet shutdowns can be requested by governors, for approval by the Interior Minister (who also serves as the chair of the NSC). If a request is submitted for internet shutdowns in multiple provinces at the same time, then the President is required to approve the order.

According to Filterwatch’s source, the recent internet shutdown in Sistan and Baluchestan appears to have been the first time that internet shutdowns were implemented in accordance with this resolution. It remains unclear whether or not this process was followed for implementing the more recent internet disruptions in Khuzestan.

Why are Localised Internet Shutdowns on the Rise?

The November 2019 nationwide shutdown represents a dark landmark in the history of Iran’s internet. Although it remains the only national shutdown implemented in the country to date, it offered a clear demonstration of Iran’s capacities to restrict access to the global Internet, while maintaining core domestic services and infrastructure. Since then, the increasing trend towards frequent, highly localised internet shutdowns is a worrying development that has posed challenges for anyone working to document and advocate against such disruptions – they are harder to spot, time-limited, and are so far more frequently imposed in marginalised, underdeveloped parts of the country.

All of the localised shutdowns since November 2019 were implemented following protests and social unrest, and they have all been accompanied by violent crackdowns from the authorities, resulting in deaths, injuries, and arrests. Another commonality between these shutdowns is the fact that – apart from the January 2020 incident in Tehran – they have been implemented in some of Iran’s most deprived and chronically neglected regions.

So far this included the southeastern province of Sistan and Baluchestan, which experienced a shutdown in February 2021, and endured a longer shutdown in November 2019 compared to the rest of the country, has the highest unemployment rate in Iran, and the majority of its population live below the poverty line. The province’s troubles have been exacerbated by a lack of vaccines and the additional strain of the COVID-19 pandemic on its massively under-resourced healthcare services. Sistan and Baluchestan is also home to numerous ethnic and religious minority groups who suffer serious discrimination and human rights abuses at the hands of the government, and are regularly prosecuted on the basis of their religion and ethnicity.

Similarly to Sistan and Baluchestan, Khuzestan province is also a deprived region in Iran. Despite being at the heart of Iran’s sprawling oil sector, holding around 80% of the country’s on-shore reserves, its population does not reap any of its rewards. Unemployment and poverty are a major problem in the province. Khuzestan has also been suffering from long term water shortages. While climate change contributes to these challenges, some experts believe that the province’s water crises can be attributed to government policy failures and mismanagement. Khuzestan is also home to ethnic Arab populations, who also face systematic discrimination and high levels of economic exclusion.

As the centre of some of the protests highlighted above, the social and economic conditions in these regions allow for localised internet shutdowns to be an effective intervention allowing for Iranian authorities to more swiftly crush protests. This process, which is becoming increasingly efficient with the expansion of the NIN, the furthering of Iran’s internet localisation plans, and the formalisation of shutdown processes, means that state authorities are now more able to impose internet shutdowns without notice and whenever it deems them necessary.

Human Rights and Localised Blackouts

Localised shutdowns are desirable for authorities compared to nationwide shutdowns as they are both cheaper, and easier to implement than larger-scale disruptions. They can also be highly effective in disrupting mobilisation – especially as most Iranians rely on mobile internet for internet connectivity, which further simplifies the process of imposing short-term shutdowns by only requiring the disconnection of mobile ISPs, sparing other fixed line infrastructure. Localised shutdowns also limit damage to businesses, as they can carry out their operations as normal in parts of the country not affected by the disruptions.

Despite their limited geographical reach, localised internet shutdowns can be as deadly as national ones. They seriously disrupt the flow of information, which is used to cover up human rights violations, such as the brutal use of force by state authorities against protestors. Another critical challenge of local shutdowns is the fact that they often cannot be as easily detected by network measurement tools. This means that reporting on these events relies heavily on on-the-ground reports from local sources. In the case of shorter shutdowns, information may not emerge until after the internet has been reconnected, as we saw in Yasuj in June 2021. This is extremely concerning, as such incidents could feasibly go unnoticed by observers, media organisations, and the international community.

Additionally, with the progress of the NIN, Iran could potentially maintain Internet shutdowns for longer, limiting costs, and forcing users to rely on domestic services. The domestic services that would remain online have limited security and privacy measures compared to their international counterparts, and are more susceptible to state surveillance, therefore putting users at great risk during periods of high political sensitivity.

Protests are very likely to continue to be a common feature of life in Iran, and so, on the current evidence, we can expect localised internet shutdowns to become more and more frequent as well. The formalisation of Iran’s internet shutdown decision-making processes confirms that the state perceives shutdowns as another tool in its arsenal of information controls: a challenge that should be a cause for major alarm for civil society, activists, and human rights defenders focusing on Iran.

The Future of Internet Shutdowns in Iran

As Iranian authorities are becoming less discrete about the imposition of routine internet shutdowns in Iran, domestic opposition to the localisation programme is growing. Following eight years of the Rouhani administration and its heavy investments in the NIN, the general public now rightly views that programme as nothing more than a long term measure to control the flow of information in Iran, which seeks to impose further restrictions on freedom of expressions and access to information online.

Iranian authorities must immediately cease the manipulation and restriction of internet connections in Iran and without delay and recognise the social and political rights of Iranians to access the global internet safely, securely, and without restriction, and to exercise their fundamental rights to freedom of expression and assembly.

Until Iranian state authorities recognise these fundamental rights, it is crucial that digital rights advocates, and those defending the rights of Iranians online and offline continue to monitor and document such shutdown events, and that they continue to challenge the further localisation of Iran’s internet.