On February 19, 2024, the Supreme Council of Cyberspace published the resolution “Exploring Solutions to Increase the Share of Domestic Traffic and Counteract Anti-Censorship Tools.”(alternative link) One of the most controversial parts of this resolution was clause 6, which prohibited the use of VPNs. However, given the legal drafting rules and the principle of legality in crimes and punishments, this prohibition does not equate to the criminalization of VPN use. Moreover, the Supreme Council of Cyberspace, as a policy-making body, does not have the authority to legislate or define crimes.

The Supreme Council of Cyberspace approved the resolution on November 14, 2023, after it had received the endorsement of the Leader of the Islamic Republic a month prior. However, as soon as it was publicly released, it received significant backlash from media outlets, Iranian users, and legal experts. This resolution explicitly banned the use of VPNs and anti-censorship tools for the first time.

A report from the Parliamentary Commission of Industries and Mines revealed that roughly 64% of Iranian users utilize VPNs to bypass widespread filtering in Iran. The Regulatory Authority for Radio Communications also reported that the number of internet users surpassed 116 million in the winter of 2023. Therefore, due to the filtering of platforms, messengers, and many international websites, millions of Iranian users have no choice but to use VPNs for access to everyday online services. This has caused concerns among the public about the criminalization of using tools that are essential for their daily lives.

Despite the swift reactions that followed the publication of this resolution, there is still a legal debate on whether the wording used in this resolution regarding the prohibition of VPN and anti-censorship tool use means that their use is criminalized? Furthermore, do the resolutions of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace, as a policy-making body, have the legal authority to define crimes and set punishments?

This brief note attempts to answer this question and other significant queries that have arisen in recent days regarding the VPN filtering resolution.

Has the use of VPNs been criminalized?

The law defines behaviors that “should not” be performed to maintain order and security in society, thereby criminalizing them. But these dos and don’ts are not explicitly stated. For example, the law does not state that damaging others’ property is prohibited. Instead, it states, “Anyone who damages another’s property will be sentenced to imprisonment from six months to three years.”

The severity of the prohibition determines the punishment. If the prohibition is severe, the offender will face criminal penalties such as fines and imprisonment. However, if the prohibition is not severe, the punishment will be administrative actions like losing a business license.

Accordingly, clause 6 of the resolution “Exploring Solutions to Increase the Share of Domestic Traffic and Counteract Anti-Censorship Tools” merely declares the use of VPNs prohibited without mentioning any enforcement guarantees or punishments. As such, legally, prohibition alone does not imply that the use of VPNs and anti-censorship tools is criminalized.

Was the use of VPNs not criminalized in Iran before?

According to Article 2 of the Islamic Penal Code, only behaviors for which a punishment is specified in the law can be considered crimes. In Iran, the production, sale, and use of tools for circumventing filtering have not been defined as crimes in the law.

However, there are two articles in the Cyber Crimes Law that proponents of judicial action against the distribution and use of VPNs refer to. Given the explicit text of these articles, these interpretations are incorrect. These two articles are:

Article 729 (alternative link) of the Islamic Penal Code considers unauthorized access to computer or telecommunications systems or data that are protected by security measures a crime. However, this article pertains to accessing sites that are protected by security measures to prevent the general public from accessing their information. Unauthorized access to information on such sites is considered a crime. This does not apply to accessing public websites that all users can access without a password and which have been filtered by the government for any reason.

Article 753 (alternative link) of the Islamic Penal Code criminalizes the production, publication, distribution, making available, or trading of data, software, or any type of electronic tool that is solely intended for committing a cybercrime. Accessing filtered sites, platforms, and applications is not a cybercrime that would make the production and distribution of tools to circumvent filtering subject to this article.

The Legal Affairs Department of the Judiciary has also stated in advisory opinions issued in 2013 and 2022 that referencing these articles does not justify criminalizing the preparation, sale, and use of VPNs and anti-censorship tools.

Despite the lack of a legal basis for action against the sale and use of these tools, there have always been groups within various government sectors who have advocated for severe and criminal action against the production and distribution of VPNs.

In 2019, then-Minister of Communications, Mohammad Javad Azari Jahromi was repeatedly summoned to Parliament to explain why his department had not taken action against VPNs and anti-censorship tools. In response to the MPs, he stated that since the sale of anti-censorship tools is not a crime according to the law, VPN sellers are not punished. At that time, Jahromi mentioned that VPN sellers use legal banking platforms in the country and that it is a trillion-rial industry. This raises the question, how could a business of this magnitude, operating within the country’s banking system, continue its activities without having powerful backers behind the scenes?

However, what Jahromi overlooked was that when the sale of anti-censorship tools is not a crime, the Judiciary, even if it accesses the related financial and banking channels, cannot prosecute them.

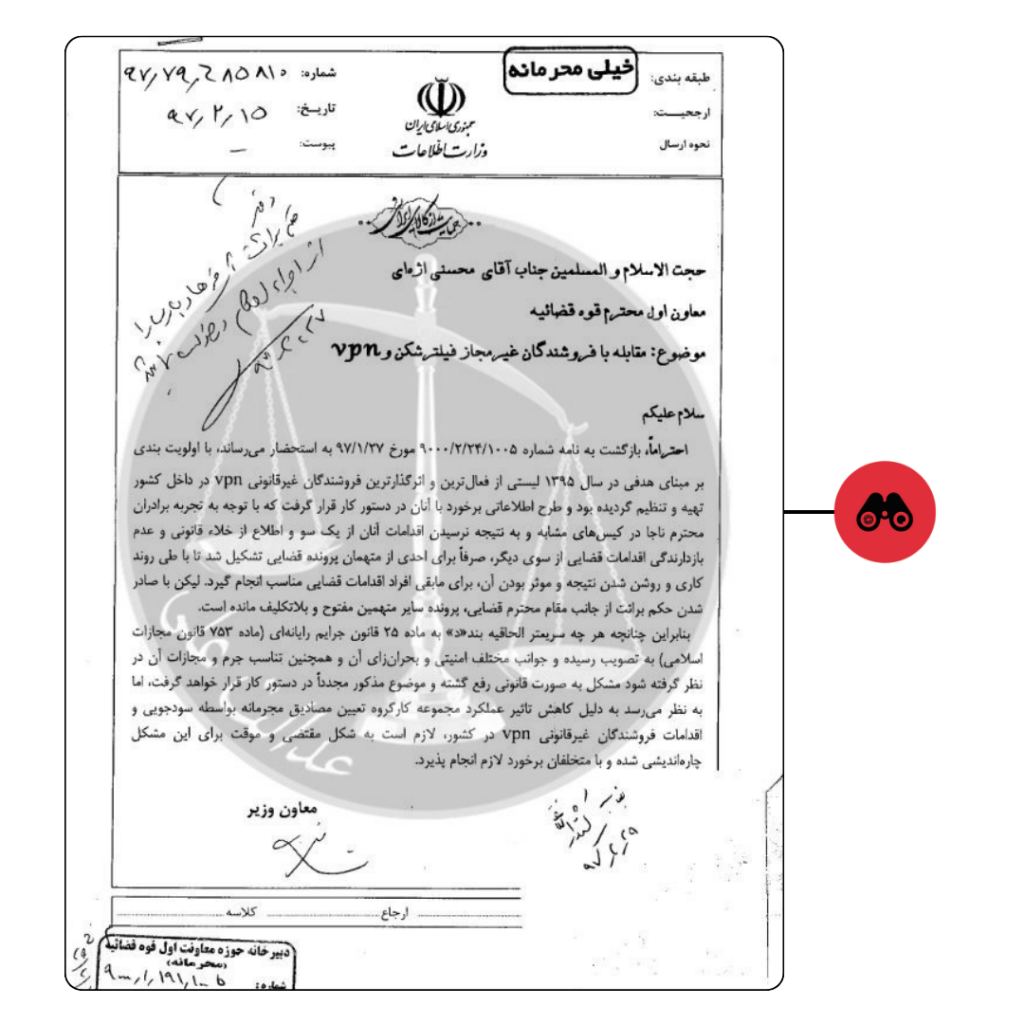

A hacker group called Justice of Ali (Edalate Ali) leaked a secret letter that the Ministry of Intelligence sent to the Judiciary in 2017. The letter said that they had gathered a list of the most powerful and active VPN sellers. But because of a legal loophole, they could not take any serious legal steps against them, and they were acquitted of charges.

The intelligence official requested in this letter that a clause be added to Article 753 of the Islamic Penal Code as soon as possible to rectify this legal loophole, allowing for criminal action against the sale and use of VPNs. He also suggested that a temporary solution be considered for dealing with VPN sellers until the problem could be resolved legally.

Filterban cannot independently verify the authenticity of this letter.

The Minister of Communications talked about the efforts to address the legal loophole make the use and sale of anti-censorship tools illegal in 2022. Isa Zarepour, the current Minister of Communications, said in a media interview on October 19, 2022 that using and selling anti-censorship tools are unauthorized, and efforts are underway to quickly criminalize the use of such tools.

Can the Supreme Council of Cyberspace define new crimes?

As mentioned above, for an illegal and prohibited act to be considered a crime, it must have a designated punishment. Merely prohibiting an act does not make it a crime unless it is accompanied by a punishment. But, if we consider the drafting of this resolution as part of the government’s official efforts to criminalize the use of anti-censorship tools and VPNs, can the Supreme Council of Cyberspace legislate?

According to Article 58 of the Constitution, the power to legislate should belong to the Parliament. However, in practice, it has been observed that resolutions from various non-elected bodies have acquired the force of law; bodies such as the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution, the Expediency Discernment Council, the Supreme National Security Council, and the Supreme Council of Cyberspace.

The problem is that a law that the Parliament passed on May 20, 2023, says that even if the Supreme Council of Cyberspace makes a resolution that goes against the Constitution, no one can challenge it in the Administrative Justice Court and annul it. The resolutions of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace cannot be disputed and they look more like laws than policies in practice. This reminds us of the Protection Bill that failed to pass parliament. In the Protection Plan, the Parliament was supposed to give its power to make laws in cyberspace to the Supreme Council of Cyberspace.

Reactions to the news of the ban on the use of anti-censorship tools

Parallel to efforts for legal and judicial action against the distribution and use of VPNs, in practice, the government blocks tools for circumventing filtering, and active VPNs are taken down one after another. For instance, reports indicate that during the Woman, Life, Freedom protests in October 2022, access to all VPNs and anti-censorship tools within Iran became almost impossible.

In a confidential letter leaked from the hacking of the prosecutor’s office by a group called Ops Iran Anonymous, the complete, effective, and continuous blocking of all unauthorized VPNs, anti-censorship tools, and filtering circumvention devices was mentioned as one of the executive solutions and proposals for organizing cyberspace.

Despite all these pressures and restrictions, Iranian users rely on and utilize VPNs for their daily online activities.

The digital marketing agency “Yektanet“, as one of the largest online advertising platforms in Iran, published a report on “Iran Digital Marketing 2022” that includes statistics on the use of VPNs by Iranian users. According to this report, 80 percent of people across various age groups used VPNs in 2022, and the annual turnover of VPN buying and selling in Iran for that year was approximately 25 to 30 trillion Iranian Rials. Based on a report by the Parliament’s Industry and Mines Commission published in August 2023, the share of anonymous bandwidth in the international network has quintupled in one year. Anonymous traffic refers to traffic that the filtering system is unable to identify the protocol of.

Due to the high volume of use and the large number of users, when news of the ban on the use of VPNs was published, it generated widespread reactions in society and on social networks, and some officials were forced to respond. For example, on February 21, Minister of Communications Zarepour, in response to the publication of a decree by the Supreme Council of Cyberspace to the media, stated that the criminalization of using VPNs has not yet been communicated to us. Bahadori Jahromi, the government spokesperson, also said in a TV program that the ban on the use of VPNs applies to government agencies, not the public.

Despite the backlash, the government and other state bodies are determined to limit the use and access of VPNs, and they have shown it by a decree from the Supreme Council of Cyberspace. But we don’t know what the government will do next to limit VPNs, and what tools and documents they will use.