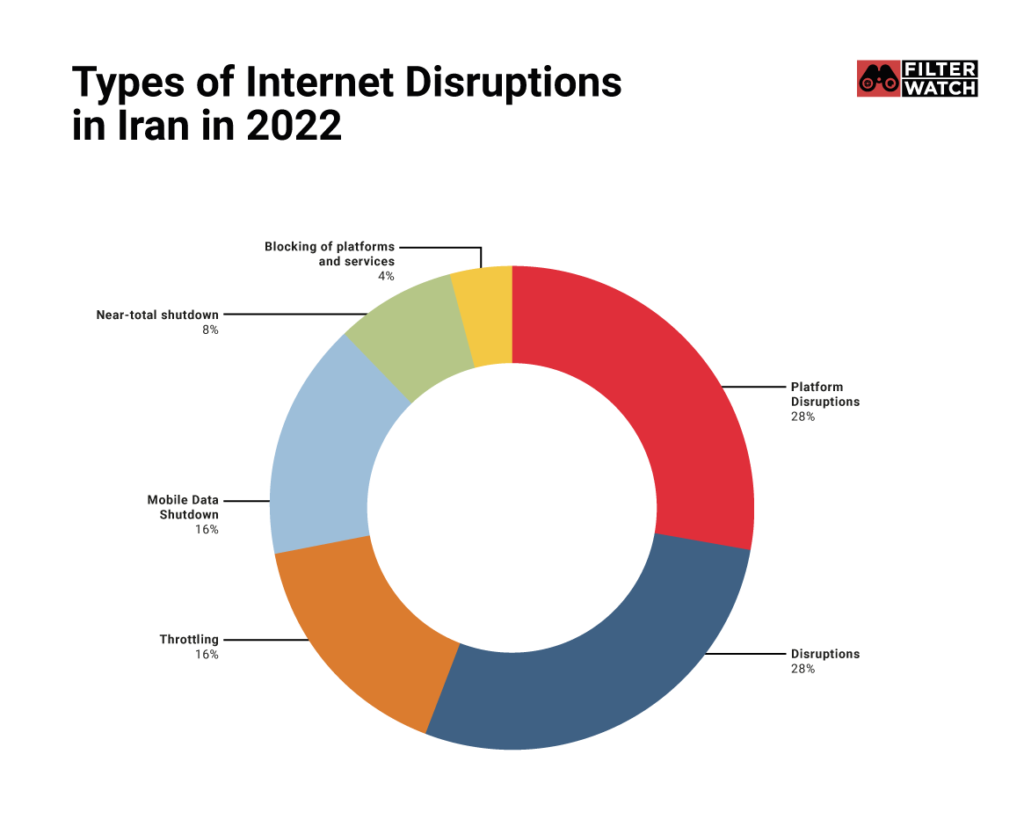

In 2022, Iranians experienced waves of internet shutdowns, disruptions, throttling and of course the blocking of various platforms and websites. Owing largely to the intensity and frequency of protests since September 2022 following the tragic death of Mahsa Jhina Amini, during at least four out of the 12 months in 2022, Iran’s mobile data was shut down either at provincial or national level, and more than 20 social media platforms, communication tools, games, and search engines were blocked this year.

Taking into account the different types of internet disruptions including mobile data shutdowns, total shutdowns,and disruptions to social media traffic such as Instagram, it can be easily said that 2022 marked the darkest year in the history of Iran’s internet, where digital rights were systematically violated through tougher information controls.

Taking into account the different types of internet disruptions including mobile data shutdowns, total shutdowns,and disruptions to social media traffic such as Instagram, it can be easily said that 2022 marked the darkest year in the history of Iran’s internet, where digital rights were systematically violated through tougher information controls.

How Did These Shutdowns Happen?

Direct Orders from the Authorities

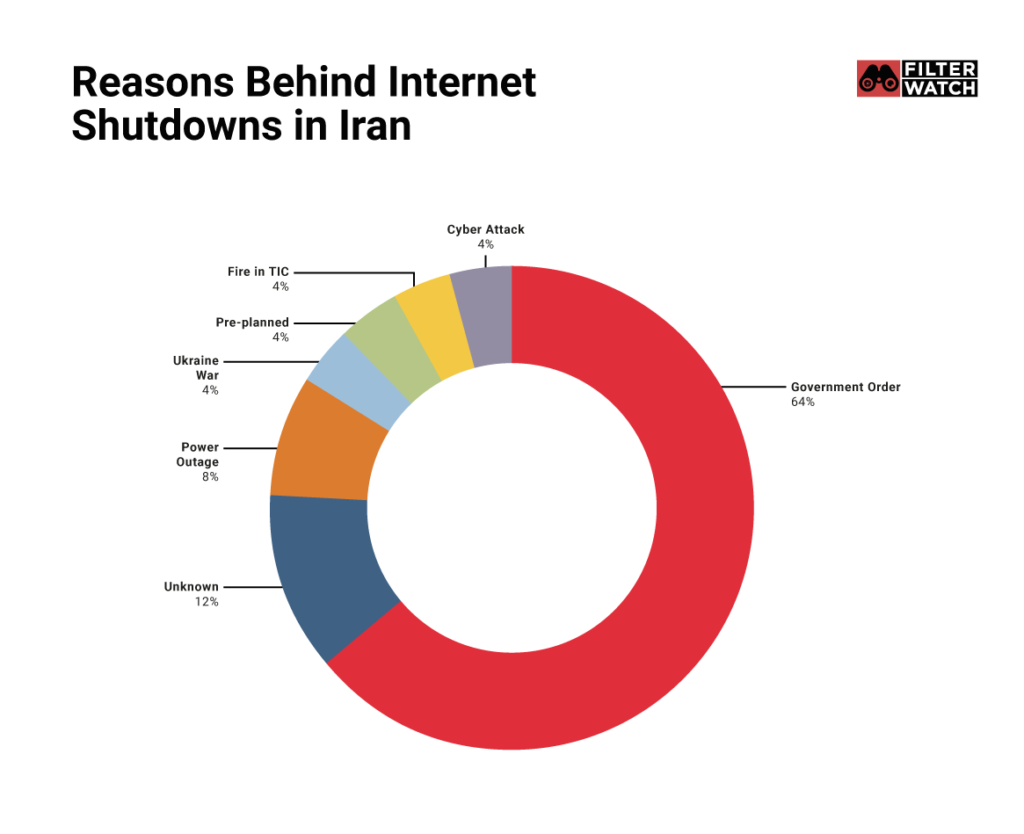

A breakdown of the variety of internet restrictions using publically available data and information shared with us as documented in Filterwatch’s monthly Network Monitor reports published throughout 2022 shows that around over 60% of all the restrictions were implemented following orders from Iranian authorities, this includes the shutdown in province of Khuzestan in May and the nationwide shutdowns in September which continued for three months.

It has been well documented that orders are almost always given during protests or politically sensitive times and excused by “security reasons” as government forces unleash violence and use of force on protestors. With this year’s intense wave of protests especially since the death of Mahsa Jhina Amini in September, it is not surprising that internet shutdowns reached new highs. It is worth noting however that we have not yet seen a nationwide internet shutdown since November 2019, with the government instead relying on localized strategic shutdowns instead. One of the reasons behind this could be related to the high costs of internet shutdowns, however, localized shutdowns are much more difficult to detect by those monitoring Iran’s internet.

There is limited information available about how internet shutdowns are ordered in Iran. In November 2019, during the nationwide internet shutdown following the fuel price protests, the then ICT Minister Mohammad-Javad Azari Jahromi stated that the internet shutdown was ordered by the National Security Council (NSC) (Persian: شورای امنیت کشور or شاک ). The body is headed by the Interior Minister, and its membership includes representatives from the ICT Ministry, Ministry of Intelligence, the IRGC, and the Armed Forces, among others.

In the aftermath of the November shutdown, in December 2019 Jahromi announced working on a bill to formalize and codify the internet shutdown process in Iran. However, according to a source close to the ICT Ministry who spoke to Filterwatch on the condition of anonymity, this bill was never introduced in the Majles due to pushback from security agencies, and the NSC. Instead, the bill became a top-secret resolution of the NSC.

According to Filterwatch’s sources, the resolution sets out the process for ordering and implementing internet shutdowns in Iran. This may have been initiated following the November 2019 protests, when Iranian authorities envisioned more frequent impositions of internet shutdowns in order to repress and silence protests. Based on information passed on to Filterwatch, province-level internet shutdowns can be requested by governors, for approval by the Interior Minister (who also serves as the chair of the NSC). If a request is submitted for internet shutdowns in multiple provinces at the same time, then the President is required to approve the order.

Accidents and Mismanagement

In 2022 power outages caused at least two disruptions, and a fire at the Telecommunication Infrastructure Company’s Large Capacity Tandem (LCT) building was the cause of another disruption. The LCT building is responsible for distributing the internet among Iran’s internet providers and other companies. Earlier this year, electrical issues led to a fire in the very same building.

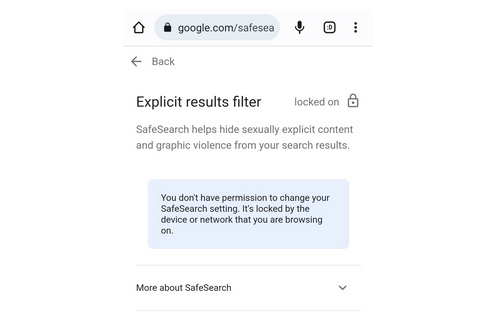

Enforcing the SafeSearch Function on Search Engines

In an aggressive move by Iranian officials in July, the activation of the SafeSearch function was enforced on all search engines, including Google, DuckDuckGo, Bing and Yandex. SafeSearch is a feature designed, in part, for children that excludes explicit content.

Since much of the content related to protests is considered violence content, this is a method of taking advantage of big tech products to impose censorship on Iranians.

Since much of the content related to protests is considered violence content, this is a method of taking advantage of big tech products to impose censorship on Iranians.

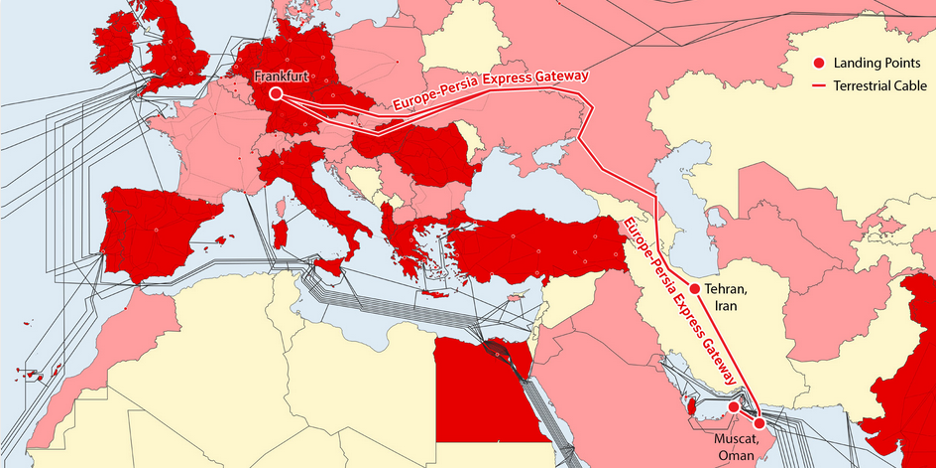

The Impact of the Russia-Ukraine War

In March Iran experienced nationwide internet disruptions due to the loss of 400G of bandwidth through the Europe-Persia Express Gateway (EPEG). EPEG is a high capacity fiber optic cable system which provides additional connectivity between Europe and the Middle East. This fiber optic cable has up to 3.2Tbit/s capacity and with a total length of approximately 10,000 km, EPEG offers route diversity by starting in Frankfurt, Germany and passing through Eastern Europe (including Ukraine), Russia, Azerbaijan, Iran and the Persian Gulf to Barka, Sultanate of Oman.

The disruption, which lasted a little more than 4 hours, can be attributed to a cut in connection with the EPEG cable that passes through Ukraine. Iran’s ICT Minister confirmed the disruption on his Instagram account and, according to the TIC website, this issue was resolved after he issued an order to find alternative routing.

Unknown Causes

Due to lack of transparency from the Iranian government regarding the reasons behind internet shutdowns and disruptions, we have not been able to identify the causes behind 12% of network issues in 2022.

Policies Contributing to the Rise in Internet Shutdowns

What the data from 2022 is telling us to expect is that in 2023, the internet and digital rights will continue to deteriorate in Iran, not only because of the technical enforcement of internet shutdowns and the blocking of content and platforms, but also because of policies that have created an environment that allow for these actions.

These policies are now coming into force with greater ease with Ebrahim Raisi as President and Eisa Zarepour as ICT Minister and others such as Rasool Jalili together at the Supreme Council of Cyberspace (SCC). Jalili and Zarepour have also worked together at the Clean Cyberspace Developers Association (فضای مجازی پاک), which is often referred to by the acronym FMP. The organization was founded by a group of hardliner policy makers which claims that its activities are mainly focused on Internet policy in Iran that support “the values and ideals of the Islamic Revolution.”

This was evidenced by the return of the so-called “User protection” Bill – which aims to achieve the opposite for those inside Iran -returned to the Majles (parliament) which is now almost entirely controlled by hardliners. The Bill has faced much resistance from civil society and the internet freedom community in Iran with more than a million people signing a petition in opposition to the Bill and more than n 40 startups and technology companies also released a statement voicing the same.

As a result of pushback from civil society, the Bill did not pass. However, Filterwatch research shows that different parts of the Bill were instead divided between different government bodies for execution and without public approval to avoid attention and scrutiny For example, three articles of the Bill were passed as a SCC resolution earlier this year. The articles now contained in the resolution relate to the role of the Supreme Regulatory Commission which is given a broad mandate to deal with any regulatory matter in the online space.

Iran’s repressive internet policies are not just limited to adults. In May, the SCC, chaired by the President, Ebrahim Raisi, approved a resolution named “The Strategic Committee for the Protection of Children and Teenagers” which approved the broad policies of Internet access for children.

The year concluded in Iran with two major internet shutdowns amid ongoing protests and demonstrations since September 2022, as well as the aggressive blocking of almost all channels and platforms for communication.