Against a backdrop of a historically low voter turnout at 42.6%, the conservative and principalists secured a massive majority in the Majles (Iran’s Parliament) during this February’s parliamentary elections.

It has now been a few months since the 11th Parliament began its term. With political alliances consolidating, and the parliament deciding its agenda and setting priorities for the coming term, there has been much speculation on the views of the new parliament on the state of Iran’s internet, form the filtering of Instagram, to new bills being introduced, and criticisms towards the “management of cyberspace” in the country.

The speculations have made headlines in recent weeks and months, but how much power does Iran’s parliament really have in controlling the internet? In this edition of Filterwatch, we examine the extent and the limitation of the parliament’s power in shaping internet policy in the country.

What Does the Majles Look Like Now?

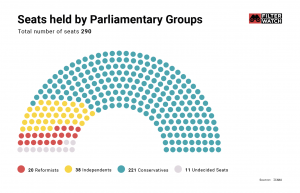

It is difficult to assign precise affiliations for Iranian politicians as there are no formal party memberships in the traditional political party sense. As such, different sources may report different figures for each faction. There are a total of 290 seats in Majles, which are filled by representatives from the country’s 31 provinces. The capital city of Tehran elects the highest number of MPs, with 30 representatives in total.

Conservatives – including hardliners – won an estimated 221 out of 290 seats, including all 30 seats in Tehran, giving them a clear majority. By comparison, Reformists only managed to gain around 16 seats, a significant reduction from the 121 seats they held in the previous Parliament. A second round of run-off elections will be held in 10 constituencies this September, in cases where no candidate was able to clear the minimum 20% vote threshold for election.

The Internet and the Majles: (How) Does it Change Things?

The composition of the parliament has opened up streams of speculation and debate about how it will shape the political trends in the country. While an important consideration for digital rights activists, the influence of parliament should be considered in view of the extent of its powers, and the power and political organisation in Iran, in order to gain a clearer view of what can be expected during this parliamentary term.

The main powers of Iran’s parliament are concentrated around passing legislation and approving the country’s budget, as well as confirming appointments or impeaching ministers. Additionally, parliament has the power to call on the government to answer specific questions which the government is required to answer.

However, in practice the authority of parliament is restricted through a number of measures. It is a considerably weaker branch of government compared to the executive and unelected bodies which are under the control of the Supreme Leader. In terms of its legislative powers, it is at the mercy of the Guardian Council, which is made up of 12 members, six members appointed directly by the Supreme Leader, and the other six are jurists appointed by the judiciary – also under the control of the Supreme Leader- and approved by the Majles. The Guardian Council can veto laws passed by parliament through its mandate to confirm the law’s “compatibility” with the constitution and Islam. Parliament also cannot investigate unelected bodies, unless by permission of the Supreme Leader.

Therefore just a few options are open to parliament to make itself more visible. Given its conservative majority against a centrist president in power, it is likely that the parliament will be using some of its authority to challenge the executive, especially as we get closer to Iran’s presidential election next year. This approach extends to internet policy and practices, as we will see in the upcoming sections.

Similar to past parliaments, the current parliament also lacks any meaningful powers to change the course of Iran’s internet policy and governance which has spent years in development and is under the control of the Supreme Leader. As we will see in the upcoming sections, the Majles has already used its more public voice to make clear criticisms and disagreement over the “management” of the country’s internet, which in itself is not especially surprising, nor does it amount to immediate changes in government. It does however create the opportunity for the Rouhani administration to frame itself as ‘defenders of a free internet’ as we get closer to the next presidential election, despite no real change in direction between the two parliaments.

Evenstill, some new faces have been elected into powerful positions in parliament, along with MPs taking up a number of roles in Iran’s various internet policy related institutions is worthy of consideration. We will look at where these changes in parliament will appear what their potential impact, if any, will be.

Despite the parliament’s limited powers, the Parliamentary Speaker can have a consequential role. This time, longtime Rouhani rival, Baqer Qalibaf, a veteran and former Mayor of Tehran, won a seat as an MP for Tehran, securing more votes than any of the capital’s other 34 MPs, which comes after his three time defeat in the past presidential elections. Subsequently, he was elected to the position of Parliamentary Speaker for a one year term, with 230 out of 290 votes from MPs. He succeeds Ali Larijani, a Rouhani ally, marking a significant moment where two out of the three branches of government – with the judiciary being headed by the conservative cleric Ebrahim Raisi – are now controlled by Rouhani’s challengers. It is also the first time a military general fills the role of Parliamentary Speaker.

The Speaker can utilise some of its powers to influence the parliament’s agenda and legislative order and to impeach Rouhani’s ministers. This can certainly impact the introduction of more legislation, of course subject to the approval of the Guardian Council, or the removal of Rouhani picked ministers.

Parliamentary Sessions and Challenges to the Government

This was evident when ICT Minister Mohmmad-Javad Azari Jahromi was summoned to parliament for a public session this June, where he spent much of his time defending the ICT Ministry from criticism from Ghalibaf and MPs over its performance. As reports on the public session emerged, it seemed that much of the focus of the session was around MP’s questioning Jahromi over the state of the National Information Network (NIN), the use of Instagram inside the country – one of the few remaining mainstream social media platforms not filtered inside the country – which raised concerns about the prospects of it being filtered in the near future, as well as a lack of support for domestic messaging apps.

Prior to the public session, Hossein-Ali Haji-Deligani, conservative MP and member of the Parliamentary Leadership Board tweeted on 12 June that Jahromi’s performance has been “weak” and that MPs have been considering “impeaching” the ICT Minister, to be followed up by motion after new parliamentary commissions had been formed. There have been similar talks also about a number of other ministers being impeached. More critical here is the fact that Jahromi’s “data protection”’ bill, which appears to have now even weaker prospects of passing should it make it to parliament.

Since the tweet, it has been reported that the motion is currently seeking MP signatures in parliament. However, the motion is yet to meet the required signature figures and has not been passed onto the Parliamentary Leadership Board.

The harsh public sessions are not a new occurrence . The ICT Minister was subject to a formal warning from Majles during the previous reformist-majority parliament, but there is still a long way between these sessions and gathering enough votes for impeachment proceedings. The question of more platforms being filtered is ever present in Iran, and tighter controls over foreign social media apps and reduction in anonymity and privacy in online spaces are not unlikely as Iran forges ahead with its internet localisation agenda.

There are a number of parliamentary commissions which are responsible for managing different aspects of ICT-related legislation, including the National Security Commission, the Industry and Mines Parliamentary Commission, and the Parliamentary Cultural Commission, among others. The commissions are noteworthy as they introduce and review pieces of legislation.

The Parliamentary Research Centre (PRC) has so far published a set of suggested priorities for the Industry and Mines Parliamentary Commission, which include the implementation of “eGovernment” systems, and the passage of data protection legislation. A draft Data Protection and Online Privacy Bill was under consideration in the previous parliament, but has not yet been passed.

Parliamentary Cultural Commission and the “Managing Social Messaging Apps Bill”

The “Managing Social Messaging Apps Bill”, which is now referred to as “Protection of User’s Rights Online and Managing Social Messaging Apps Bill”, has already been identified as posing significant dangers to digital rights in Iran has been making headlines once again as it was reportedly placed on the Parliamentary Cultural Commission’s agenda. The bill, which was in fact introduced by the Cyber faction of the previous Reformist majority parliament two years ago. It was under review by the previous Cultural Commission following its return from the PRC, however, the review was not completed before the 10th parliament ended its term.

The new version combines the recommendations from the PRC but contains almost all of its controversial articles which includes handing over control over internet gateways to the Armed Forces without any limits, as well creating an “Oversight Board” which will manage the operation of both foreign and domestic messaging apps in the country. Messaging apps that do not “comply” with the country’s rules and regulations cannot operate in the country which could mean giving powers of platform filtering to this new board.

The bill also contains some new articles not included in previous drafts. It defines the unauthorised production, publication and distribution of VPNs and circumvention tools as a crime. The article is in line with our previous analysis on “Layered Filtering” and state of legal VPNs in the country.

Despite the bill’s name change, very little here is dedicated to meaningful data protection, meaning that data protection will also onlexist y in name, and it will need to be addressed.

The bill will still need to be reviewed by the commission and to go through a parliamentary vote before it is passed onto the Guardian Council. If passed, this bill is the first major internet related bill since the Computer Crimes Law in 2008. Despite its extremely restrictive proposals on the operation of messaging apps in the country and the promotion of domestic apps, the credit should go to the previous reformis parliament and not the current one.

Policy Making Changes

The new parliament also brings changes to the membership of the Supreme Leader mandated Supreme Council for Cyberspace (SCC), the country’s top internet policy making body.

The SCC is made up of ten members appointed by the Supreme Leader, and 17 “legal members”, which includes the heads of the three branches of government, which means Ghalibaf is now a member of the SCC by virtue of his position as Speaker. The other parliamentary member is the head of the Parliamentary Cultural Commission, which is Tehran MP Morteza Aghatehrani. Additionally, Reza Taghipour, who was appointed to the SCC by the Supreme Leader, gained a seat as an MP for Tehan during the parliamentary elections and is also a member of the Mines and Industry Commission. Given that Taghipour was a member of the SCC first, he may attempt to amplify SCC’s policies in Majles, however in terms of the makeup of the SCC this does not change the dynamics of the council as the Supreme Leader’s appointments and government members outnumber the parliamentary members still.

The SCC carries out the vision of the Supreme Leader for Iran’s internet, which is focused on localisation through the completion of the National Information Network (NIN) and wields a large amount of influence with its resolutions, which guides legislation and the workings of relevant ministries (such as the ICT Ministry). The direction is highly unlikely to change with the arrival of the new members. However, since the beginning of the year, SCC meetings have only been held twice at most, instead of every six weeks as it is required to do. The lack of meetings have been a cause for criticism from MPs, who have according to Taghpour, proposed new legislation which will address the “involvement of Parliament in completing the NIN”.

There will also be membership changes to the Committee for Determining Instances of Criminal Content (CDICC), which officially holds the responsibility of deciding on the filtering online content, which is important to consider when it comes to the question can parliament filter platforms and services. The CDICC is made up of 12 members, who are supposed to meet every 15 days, two of which a representatives from Majles, namely:

“An expert in ICT, chosen by the Parliamentary Mines and Industry Commission and a member of the Parliamentary Judicial and Legal Commission (confirmed by Parliament)”

According to the Computer Crimes Law (CLL), the decision of the Committee is passed by a majority vote, which is quorum with seven members present. As we can see, government representatives outnumber the parliamentary appointments, therefore, without agreement from other CIDCC members, parliamentary representatives cannot enforce their choice.

However, in recent months there has been disputes and claims from the ICT Ministry that meetings have been taking place without a quorum. Therefore it is worth bearing in mind that the Judiciary – under the control of another Rouhani rival, Ebrahim Raisi – wields much more power in making filtering decisions than the CIDICC, as we saw in the case of the filtering of Telegram. While it is not entirely unlikely that more platforms will be filtered as part of the the National Information Network (NIN), it is worth remembering the procedures and the involvement of the various government organisations in the process.

What Can We Do Now?

As we have seen, the role of Majles overall is quite limited, regardless of its ideological leanings and affiliations, and the same goes for influencing internet policy. As a result is is difficult to expect many dramatic changes from this parliament compared to the last, and as we already mentioned, some of the controversial measures such as the “Managing Social Messaging Apps” is in fact the legacy of the pervious Majles, making it hard to say that the conservative majority will be any more harmful to Iran’s internet that the past reformist ones.

What we can expect are a number of more disruptive rhetoric and motions that will amplify the criticisms of President Rouhnai’s supporters in government in a bid to appear as though parliament is exerting more control and power. However, the moves are unlikely to change the fundamentals of internet localisation that has been ongoing for years in the country. Given this assessment, it remains an important factor in deterring further damage done by the Iranian authorities. Although the new parliament is unlikely to deliver significant legislative changes in the short-term, they may succeed in obscuring the debate inside Iran by framing Rouhani’s Administration as defenders of liberal internet and digital rights. In light of this it is imperative for digital rights advocates to maintain a focus on fighting forced Internet localisation and new methods of information control such as layered filtering.