Iranian women’s privacy and freedom have been increasingly violated through the government’s use of technology, especially after the Women, Life, Freedom movement. The government has a long history of using technology to spy on Iranian citizens, such as SIAM, facial recognition, e-government services, surveillance tools developed by the prosecutor’s office, and the Nazar mobile phone application.

The Iranian government is not only using technical tools, but also implementing policies to spy on Iranians, with women bearing the brunt of these measures. One of these policies is the “People’s Lifestyle Assessment System”, which was approved in the “Seventh Development Plan” bill. This system aims to track the every move of Iranian citizens.

Against this backdrop, FilterWatch has obtained an Android application called Nazer, which the national police force of Iran (formally known as the Law Enforcement Command of the Islamic Republic of Iran, or FARAJA based on its Farsi acronym) uses to report people and their vehicles who violate the hijab law. Nazer is a Persian word that means “supervisor” or “overseer”.Our research shows that the app can only report vehicles with improper hijab for now. But static analysis of its code reveals with potential future updates, the app could also be used to report people for protesting, drinking alcohol, cruising around in vehicles, and other things the government deems criminal.

In its current state, Nazer is a suite of software that covers various aspects of public and private life, and relies on the participation of “spontaneous public forces”, or vetted volunteers who act as hijab enforcers and use the Nazer app to report offenders.

This report examines the history, features, and implications of Nazer. It argues that it is a digital tool for repression and surveillance, as it lets police officers or their approved volunteers make decisions without any independent judicial oversight, thereby violating international human rights law on access to a fair trial.

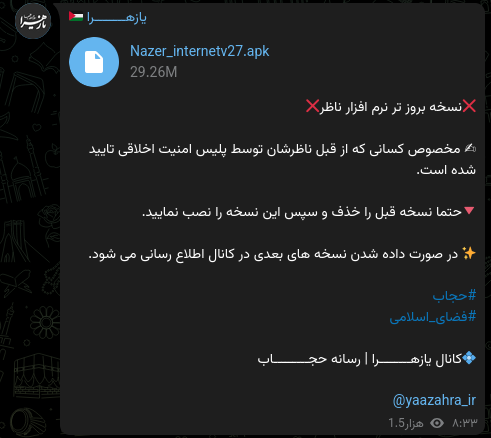

The Nazer system is not available on any app stores or public websites, making it difficult to access and analyze by independent researchers and journalists. However, we were able to find the application on the police website as well as on a channel on Eitaa, which is a domestic messenger app. The channel is named Ya Zahra and belongs to someone named Mohammad Yousefi.

According to the information on the channel, Ya Zahra is the media arm of the Hijab Strategic Council, a semi-official body that promotes and defends the compulsory hijab law in Iran.

Based on our technical analysis of the app, even though this application has been publicly accessible on Eitaa, any potential user and their device must be approved by FARAJA before use it.

The Nazer app also contains a PDF manual embedded into the app, named nazer.pdf. According to the data extracted from the metadata of this file, this file was created on 2021:05:10 16:51:07+04:30 (Afghanistan Time Zone) on Microsoft Word by someone named Nazanin Zarezadeh.

According to the information in this manual, the entire purpose of this app is to report those who are not wearing a proper hijab. However, there is no definition of proper hijab in the manual.

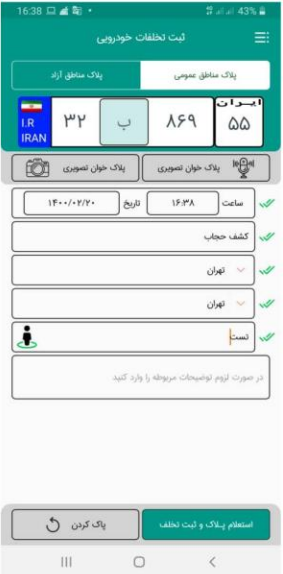

This app depends on the operator who enters data on it. In other words, if an authorized user observes a women’s hijab and deems it improper, they can enter information such as license plate number, time and date, city, vehicle model, and address. Of note, there is no facial recognition technology in the app nor is it designed to take pictures of faces. The only picture taking option in the app is taking a picture of the license plate number.

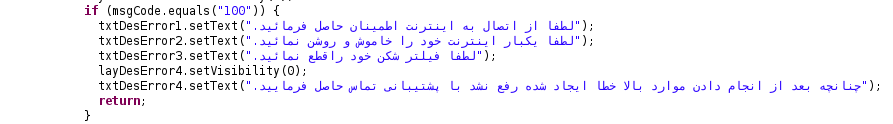

The Nazer app only works on the National Information Network (NIN), a state-controlled intranet that aims to isolate the domestic internet from the global network. The app detects if a VPN is on, and asks the user to turn it off. This shows FARAJA expects their officers to run the app on their personal devices and also suggests that the police are aware that their officers are using VPNs to bypass internet censorship and access blocked websites.

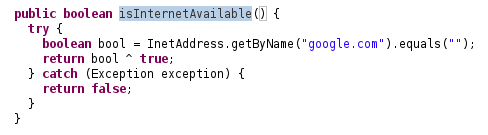

The app also checks whether it has access to Google.com or not, to test whether the internet is available or not. This means that if Google.com is disrupted for whatever reason, such as technical issues or even internet shutdown, then the app will not work.

The Nazer app uses two APIs to perform its functions. The first API is https://nazer.police.ir/nazer/napi, which is used for license plate inquiry.

The second API is https://api.neshan.org/v1/, which is used for searching addresses in the app. This API is provided by Neshan, a domestic map and navigation service that claims to be the most accurate and up-to-date map of Iran. This is a public service, and like Google Map, anyone can register and request for API.

The Nazer app also has a support ticketing system, in which a user can submit a question and a support team will provide an answer. Here are some of the questions and answers that we found in the app:

Q1: How do we report on motorcycles?

A1: So far we do not support motorcycles reporting.

Q2: Apart from NAJA (police) personnel, do other organizations have this software?

A2: Yes.

Q3: Walking dogs and noise pollution have also increased. Is it possible to register these violations?

A3: No, only hijab violations are registered.

The Nazer app also has a hidden feature, that could potentially be unlocked in future updates, which would allow its authorized users to report other types of violations, such as:

- Public rioting or disturbances, which is usually referring to protesters by security services

- Bad hijab or removing hijab

- Drinking alcohol and driving while intoxicated

- Harassment of women

- Noise pollution

- Eating or drinking in public during Ramadan

- Cruising the city streets (an activity known as dor, dor in Iran)

- Behavior contrary to public decency

This feature is not operational yet. However, it indicates that the Nazer system has a broader scope and agenda than just hijab enforcement, and that it can be used to monitor and report any behavior that the government deems undesirable or unlawful in future.

History of the Nazer Project

The Nazer project was first rumored in May 2019, when some citizens received a text message from FARAJA, indicating that they had committed a “crime of unveiling” in their vehicle and that they had to visit the local police within a specified period for investigation. This sparked public outrage and confusion, as many people claimed that they had received incorrect messages, and that the Nazer project, which the designers claimed was necessary to “strengthen the family foundation”, had actually caused familial problems and disputes. The judiciary’s spokesperson at the time acknowledged these issues, highlighting the system’s initial challenges and public pushback.

However, despite the public backlash and criticism, the Nazer project did not stop. On the contrary, current evidence shows that after the outbreak of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement last year, the scope of the Nazer project has expanded.

The first evidence to support the expansion of the Nazer project is a directive from the Amr-e Be Maroof (commanding right and forbidding wrong) headquarters, a religious and moral authority that oversees the hijab enforcement, issued in late February 2023 to some institutions and organizations. This directive asked interested employees to coordinate with FARAJA and use its software if they wished to participate in the Nazer project. This directive indicates that each of the “spontaneous public forces” must request collaboration from FARAJA, which can be interpreted as a request for permission.