Iran — like just about everywhere else in the world — has seen the inexorable (and some might say inexplicable) rise of a class of Instagram ‘influencers’. These stars of online media have found themselves with tens or even hundreds of thousands of devoted followers, along with a massive level of social and cultural influence.

Influencers have developed their own subcultures around food, music, film and comedy, with others broadcasting politically and socially-minded content. However despite their expansive, and often devoted follower bases, most big influencers remain relatively unknown to the wider public.

So last month was a strange time, with mainstream Iranian news programmes starting to show interest in the recent posts of Iran’s top influencers. In particular, a number of apolitical female influencers started to post videos and pictures of themselves in ‘good hijab’ — conservative varieties of hijab that could likely pass the tests of even the most conservative producer on state TV broadcaster IRIB.

This only made its way into the headlines when a Tehran-based Instagram ` and food blogger made a public statement about her decision to wear ‘good hijab’, deleting her old posts. She said: “I have been asked join the project to ‘sanitise’ cyberspace, and I have enthusiastically accepted the call.” According to IranWire, representatives from FATA have been contacting Instagram influencers and warned them that they had a week to remove hijab-free content, and that they risked ‘losing their profiles’ if they failed to comply.

Since then a number of reports have surfaced claiming that Instagram influencers had been summoned by Iran’s Cyber Police (FATA) and warned to change their appearance, which was deemed not to be in compliance with the requirements of Iran’s dress restrictions. FATA itself has yet to comment on these reports.

In this issue of Filterwatch we take stock of FATA’s continued influence over discuss how these methods may become more and more common in the coming years, with FATA’s far-reaching ‘social policing’ ambitions representing a serious and often-ignored threat to digital rights in Iran.

Looking Back: A Brief History of FATA

2009–11 // Origins

In February 2009 Iran’s former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s cabinet approved a strategic document dedicated to national security and crime online, which laid the foundation of what we now know as Iran’s Cyber Police, or FATA.

The document makes it clear that coordination of national security policy is to be led by the government — specifically the Interior Ministry and the Intelligence Ministry. For the following two years, Iran’s Police Force started implementing cyber-policing into its operational scope, and on 23 January 2011 FATA was founded as an independent force within the Iranian Police Force. FATA is currently headed by Seyyed Kamal Hadianfar, who has been in his position since 2011.

2012 // The Case of Sattar Beheshti

While many assumed that FATA played an active role in crackdown on protesters and political activists during the events following the disputed 2009 presidential election, it was the death of the Iranian blogger Sattar Beheshti in November 2012 that led to widespread national and international recognition of the role that FATA played in violating human rights in Iran.

Sattar Beheshti was a young Iranian blogger who was arrested by FATA on 30 October for writing blog posts critical of the government, and died in police custody several days later. His family and human rights organisations have been adamant that he was subject to torture and mistreatment in custody, and that these abuses were responsible for his death. A public outcry led to a parliamentary investigation into the matter. The National Security Committee-led investigation was widely condemned for basic inaccuracies about the incident, though it did condemn FATA for its role in Beheshti’s death. On 26 November Mehdi Davatgari — one of the MPs involved in the investigation — called for the Chief of FATA Seyyed Kamal Hadianfar to be replaced.

However, the investigation ultimately did little to damage FATA’s position in the long run. Although the Beheshti incident resulted in FATA being subjected to new EU and US sanctions, FATA continued to exert its power as the key implementer of Iranian cyber policing.

2018–19 // FATA Today

Eight years on, FATA is an established force in the Iranian security landscape. Since the death of Sattar Beheshti, it has generally managed to avoid significant levels of international scrutiny. Yet despite managing to avoid the spotlight, FATA continues to exert a powerful effect on the country’s online media ecology.

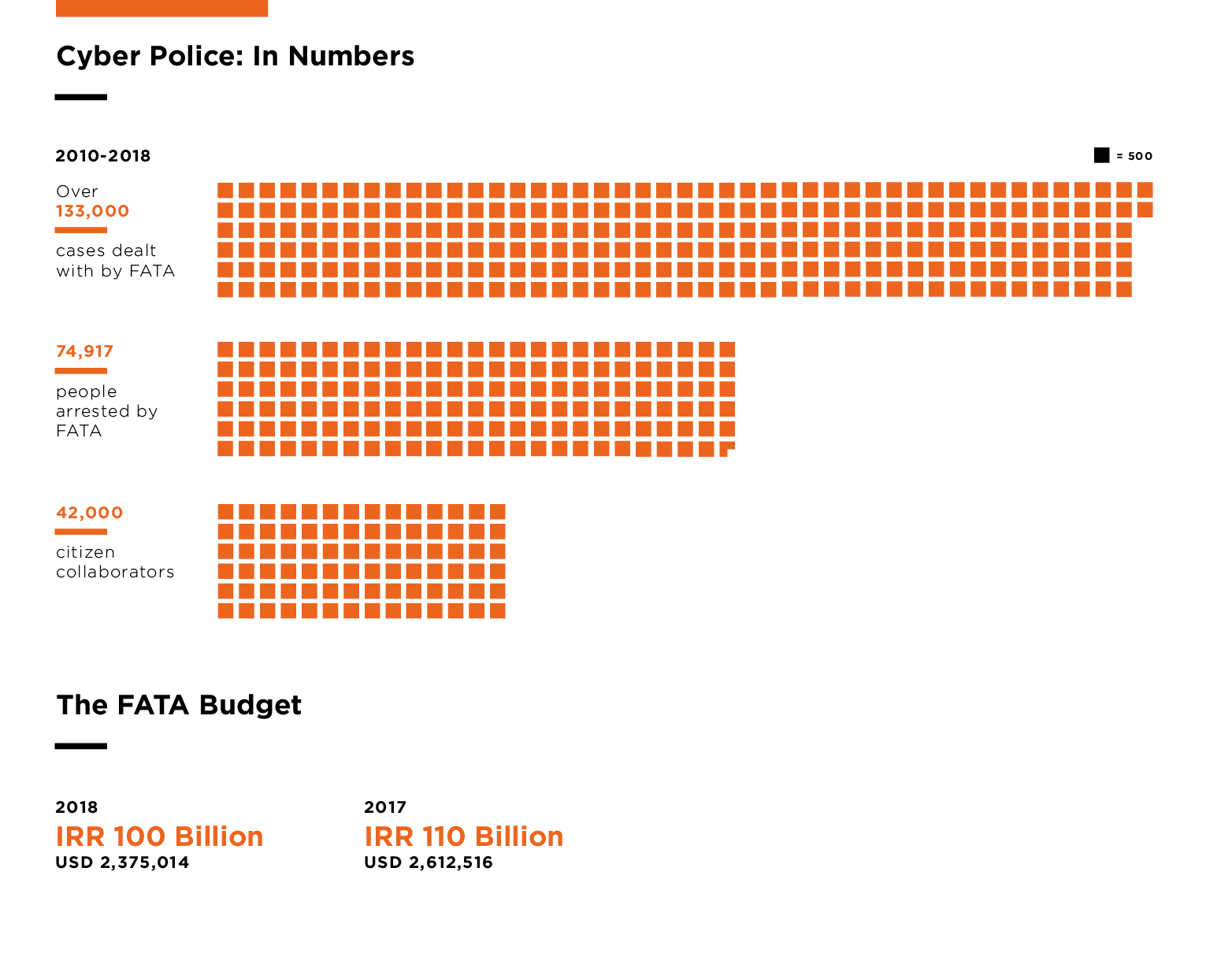

On October 10 2018, FATA Chief Seyyed Kamal Hadiyanfar announced that in the last eight years, FATA has been involved in more than 133,000 legal cases, making nearly 75,000 arrests. While cases such as that of Sattar Beheshti’s, and of a young Iranian woman detained in July 2018 on the basis of her dance videos received widespread attention, there has been next-to-no media scrutiny of this huge number of arrests.

FATA and the Rise of Peer Surveillance

‘Every Citizen a Police Officer’ // The Growth of Peer Surveillance

FATA’s lack of transparency has meant that very little information is available about what happens to Iranian internet users arrested by FATA, the level of legal assistance available to them, and any requirements for sharing their data with the organisation.

This lack of transparency also means that today we have little information about how investigations are carried out by FATA. In light of Iran’s established policy of discouraging the use of encrypted services, one can assume that a level of technical surveillance is involved in the security forces’ (including FATA’s) monitoring and investigation of Iranians’ online activities. However, the security services aren’t wholly reliant on technical surveillance; recent comments by FATA’s Deputy of Social Affairs Colonel Ramin Pashayi on 19 December confirmed the integration of widespread peer surveillance into online law enforcement.

In his interview, Pashayi boasts about the recruitment of 42,000 civilian volunteers since March 2014. In this alarming Interview, Pashayi stated that FATA’s approach to policing was one of ‘society-based policing’, with the aspiration of creating a culture of ‘every citizen a police officer’. In practice, this amounts to create an environment for participatory, peer-led surveillance of online communities.

According to Pashayi, volunteers can sign up to work with FATA through their website. He added that at present, volunteers take part in a range of activities including monitoring online spaces, content production and content promotion.

FATA’s large-scale volunteering drive shouldn’t be taken to imply that it’s strapped for cash — the body still enjoys substantial financial support from central government. FATA’s share of the national budget for the current Iranian year (2018/19) is 100bn IRR (2.38bn USD), with a rise to 110bn IRR (2.6bn USD) projected in the latest draft of the proposed budget for 2019/20.

The World Stage // Ongoing International Cyber Policing Partnerships

It also must be noted that despite the sanctions, and the outcry which followed the death of Sattar Beheshti, FATA today is far from isolated. On a number of occasions they have boasted about their international collaboration and partnerships with global online law enforcement agencies. Even on 4 September 2013, only months after new sanctions were imposed, the Chief of FATA boasted about the agency’s system of information exchanges with 132 national police forces.

On its website FATA boasts about its membership of “No More Ransom”, an initiative of the Netherlands’ National High Tech Crime Unit, Europol’s European Cybercrime Centre and the digital security service provider McAfee. The initiative’s stated aim is to help victims of ransomware retrieve their encrypted data without having to pay ransom money to criminals.

Iran’s involvement in this programme raises questions about the extent to which the international community is willing to cast a blind eye to FATA’s past human rights abuses. Although we would not advocate for FATA’s expulsion from programmes such as this, we would question whether the normalisation of FATA might leave the door open for them to participate in other cooperative programs that could boost their capacities to surveil citizens and crack down on political dissent.

In May 2018 the Chief of FATA Brigadier General Seyed Kamal Hadiyanfar met with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Iran Country Representative, Alexander Fedulov. The meeting took place on the margins of the opening session of the 6th EURASIA Working Group Meeting on Cybercrime for Heads of Units, which took place in Tehran.

Understanding the Dangers

FATA Poses Unique Risks to Digital Rights

Perhaps one reason FATA doesn’t get the attention it deserves as a violator of citizens’ rights is the attention given to Iran’s so-called ‘Cyber Army’, and groups allegedly close to — or backed by — Iran’s Revolutionary Guard (IRGC). While those groups have targeted high-profile activists or foreign entities, FATA’s victims are often ordinary Iranians without access to national and international media coverage, or without the will to publicise their treatment at the hand of FATA.

We should also stress that a substantial proportion of individuals arrested by FATA would be considered criminals under most legal systems — among those detained are online fraudsters, blackmailers, and purveyors of child pornography. However in the absence of any meaningful transparency on the part of FATA, and the organisation’s previous track record, serious concerns remain that significant numbers of people are detained under illegitimate or trumped-up charges.

The neglect of FATA’s record is so great that the only organisation that has loudly boasted about the numbers arrested by FATA, their volunteer base, and their social reach is FATA itself. This self-advertising is emblematic of the role FATA is seeking to play in Iran’s evolving regime of information controls.

As we discussed in our previous reports, Iran appears to rely less and less frequently on the blunt instrument of mass filtering, and more so on other methods in shaping access to information in Iran. We have previously outlined challenges such as the erosion of net neutrality as a tool of information controls, but the ‘society-based policing’ model we have outlined here (or to call it what it is — ‘participatory’ or peer surveillance) should be viewed as a new tool in Iran’s arsenal. FATA’s boasts about its reach should be seen in this light as a means to talk up the reach and effectiveness of its surveillance efforts.

The fact that famous influencers have changed their behaviour based on FATA’s interventions, and that they have publicly advertised doing so as the result of ‘a state-backed initiative’ must be viewed as victory for FATA and other implementers of social policing in Iran.

In the same way that forced TV confessions are designed to create fear among activists and campaigners, FATA’s boasts about the massive number of arrests they have made, their ability to monitor social media at a large scale, and their successful transformation of the behaviour of Instagram influencers all constitute components of a concerted public campaign designed to sow fear among Iranian internet users.

The Risks of Peer Surveillance for Marginalised Communities

There is also another significant cause for concern in studying FATA’s policing methods and rhetoric. Relying on volunteer informants and manual monitoring is likely to entrap users in smaller virtual communities or less populated urban and rural areas. Two groups that for different reasons may even be more vulnerable to policing and legal system that does not grant sufficient legal rights to those detained or accused of crimes.

Smaller virtual communities such as the LGBTQ community — which uses the internet in Iran for peer support and community-building — face particular risks under the policing model being championed by FATA. In our recent report Breaking the Silence we documented how the LGBTQ community already faces entrapment and online harassment, in some cases from individuals claiming to represent FATA. Ongoing ambiguities around FATA’s level of engagement against the LGBTQ community has created an atmosphere of fear among many LGBTQ internet users.

It is in this environment that slogans such as “every citizen a police officer” are designed to evoke a culture of peer spying that cannot easily be countered through conventional digital security practices. In this sense, the strategy is designed to shatter any illusions that users in Iran can enjoy a level of immunity on online life that is not afforded to them offline

Similarly the peer surveillance methods are likely to lead to greater criminalisation of internet use among those living in smaller town and village. In the exact same way that is much harder for one to have a private offline life in a village than in a large city, small town users that post ‘problematic’ content on their community Telegram channel may also find themselves much more vulnerable to peer surveillance then those living in larger towns and cities.

The prospect of further surveillance of already marginalised communities should be a serious cause for concern for anyone interested in human rights in Iran. These examples are also communities for which barriers exist relating to political sensitivities, and a lack of sophisticated social and legal support structures in the event that individuals are detained by FATA.

Introducing FATAwatch

Given the serious threat that FATA poses to citizens’ online freedoms, we believe there is a real need for further scrutiny of their actions. The fact that we heard next to no details about the process by which the 75,000 people were identified and arrested, their treatment once detained, and their legal rights in detention demonstrates that there is an urgent need for greater transparency and fundamental reforms in the operations of FATA. Sadly all evidence points to a continuation of the agency’s heavy-handed approach and regime of secrecy in its mobilisation of its new force of citizen volunteers.

Iran’s lawmakers cannot claim to be concerned about digital rights, access to information, and policing justice if they do not immediately raise concerns about the ongoing behaviour of FATA. Sadly, the issue has failed to receive any meaningful attention from even the self-described reformist lawmakers in the Iranian Parliament.

Given this ongoing lack of scrutiny, we at Small Media have decided to launch a new quarterly report investigating the data that is publicly available about FATA, and aiming to cast new light on the agency’s secretive operations.

FATAwatch will be published four times a year, and will provide raw data and analysis about arrests made by FATA, the agency’s public campaigns, and their continued impact on digital rights in Iran.