Over the past month, Iran’s digital landscape has been plagued by widespread internet disruptions, blocking of WhatsApp voice and video calls, and GPS malfunctions.

At the same time, authorities arrested managers of the Rasmio platform and seized its database, shut down the online petition site Karzar, and barred the founder of the Divar app from taking the company public. Together, these moves send a clear signal: Iran’s digital space is increasingly controlled by security forces.

Even the controversial “Bill to Combat False Content in Cyberspace,” which was withdrawn under public pressure, demonstrated the government’s persistent efforts to expand its control over cyberspace through new legislative measures.

Together, these events paint a worrying picture of digital governance in Iran. The current path—a combination of legal restrictions, structural discrimination in access, and forced localization—reflects the government’s belief that these measures can keep Iran “safe” and independent of the international internet during future crises like the recent “12-Day War.”

Key Findings:

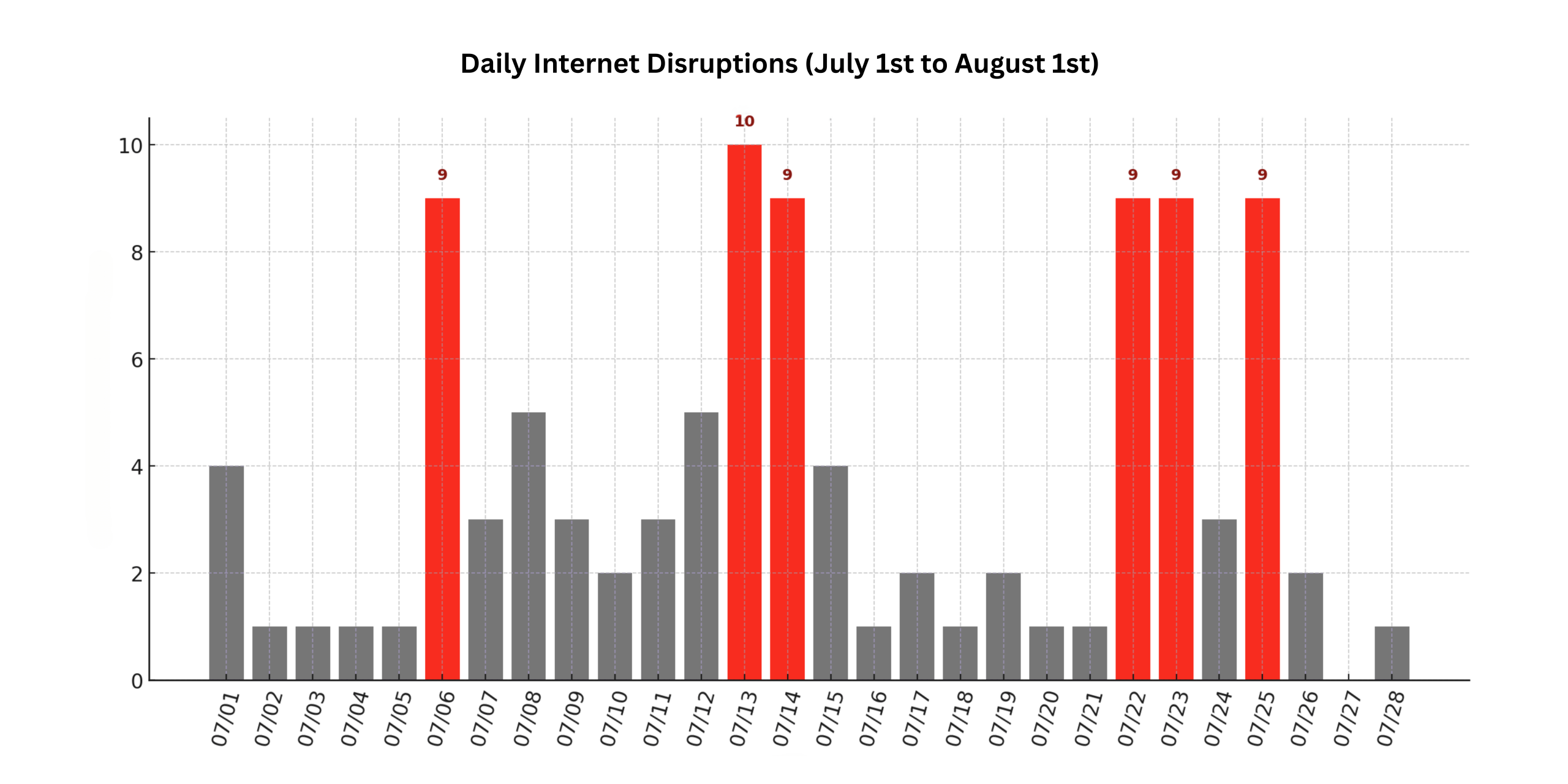

- Widespread Disruptions: At least 102 significant disruptions to Iran’s internet network were recorded in July and early August 2025.

- GPS and Geopolitical Shifts: Ongoing GPS disruptions are driving high-level policy discussions about migrating to China’s Baidu satellite navigation system.

- Persistent Security Flaws: Despite significant resource allocation, 51% of executive agencies report continued security vulnerabilities and the need for network security upgrades.

- Security’s Grip on the Economy: Security agencies are playing an increasingly direct role in managing the digital economy, influencing which startups can enter the stock market.

- Intensified Crackdown on Startups: Security-driven actions against startups and digital activists serve as a stark warning to the entire digital ecosystem.

- Failed Censorship Bill: While a government bill to restrict freedom of expression online was not passed, concerns remain that its provisions are being implemented unofficially.

- Expanding Digital Discrimination: The policy of a “tiered internet” and digital discrimination is being expanded through new regulations and “localization” plans.

- Widespread Disruptions: At least 102 significant disruptions to Iran’s internet network were recorded in July and early August 2025.

Review of Internet Access and Network Infrastructure in Iran

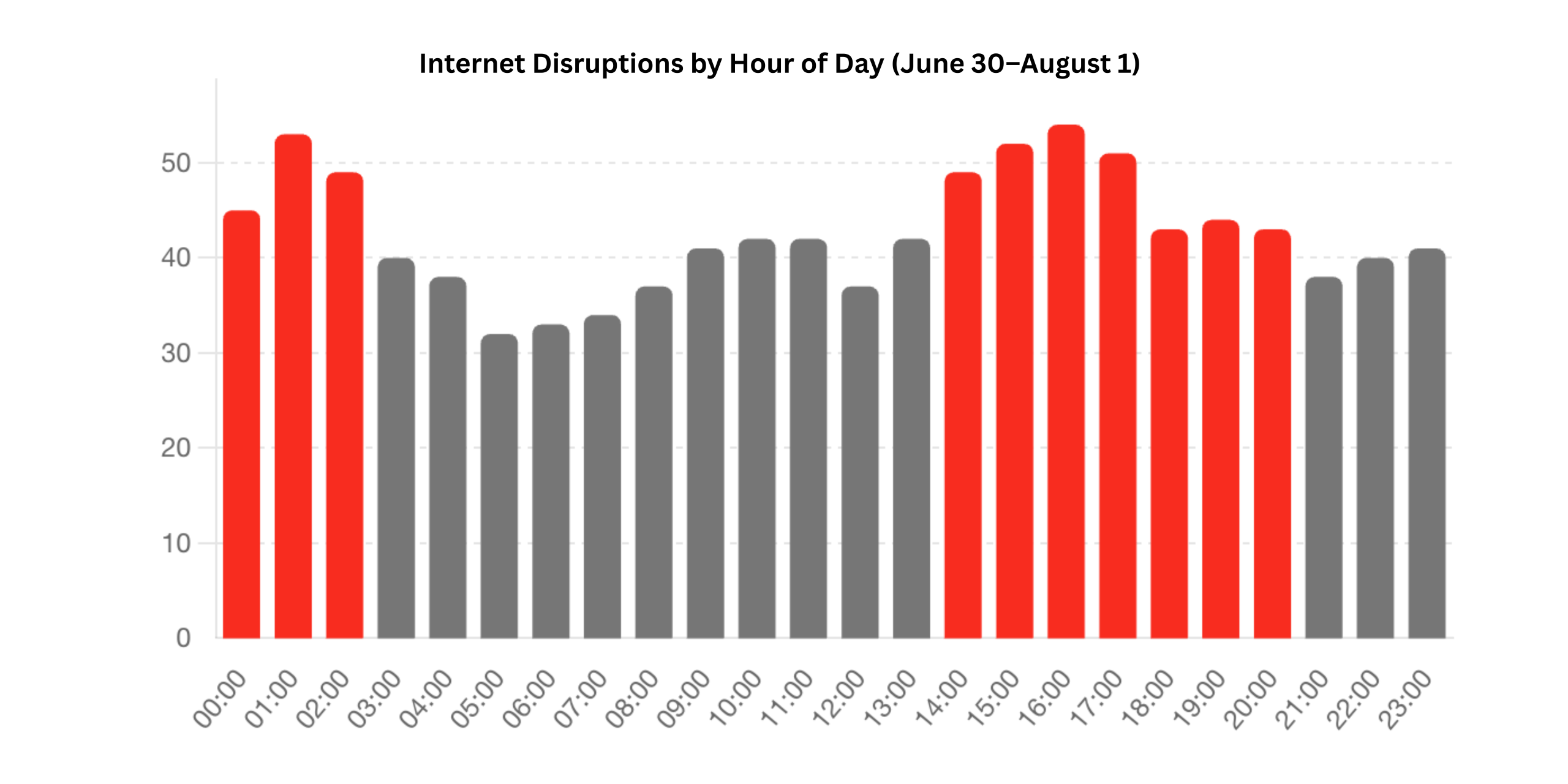

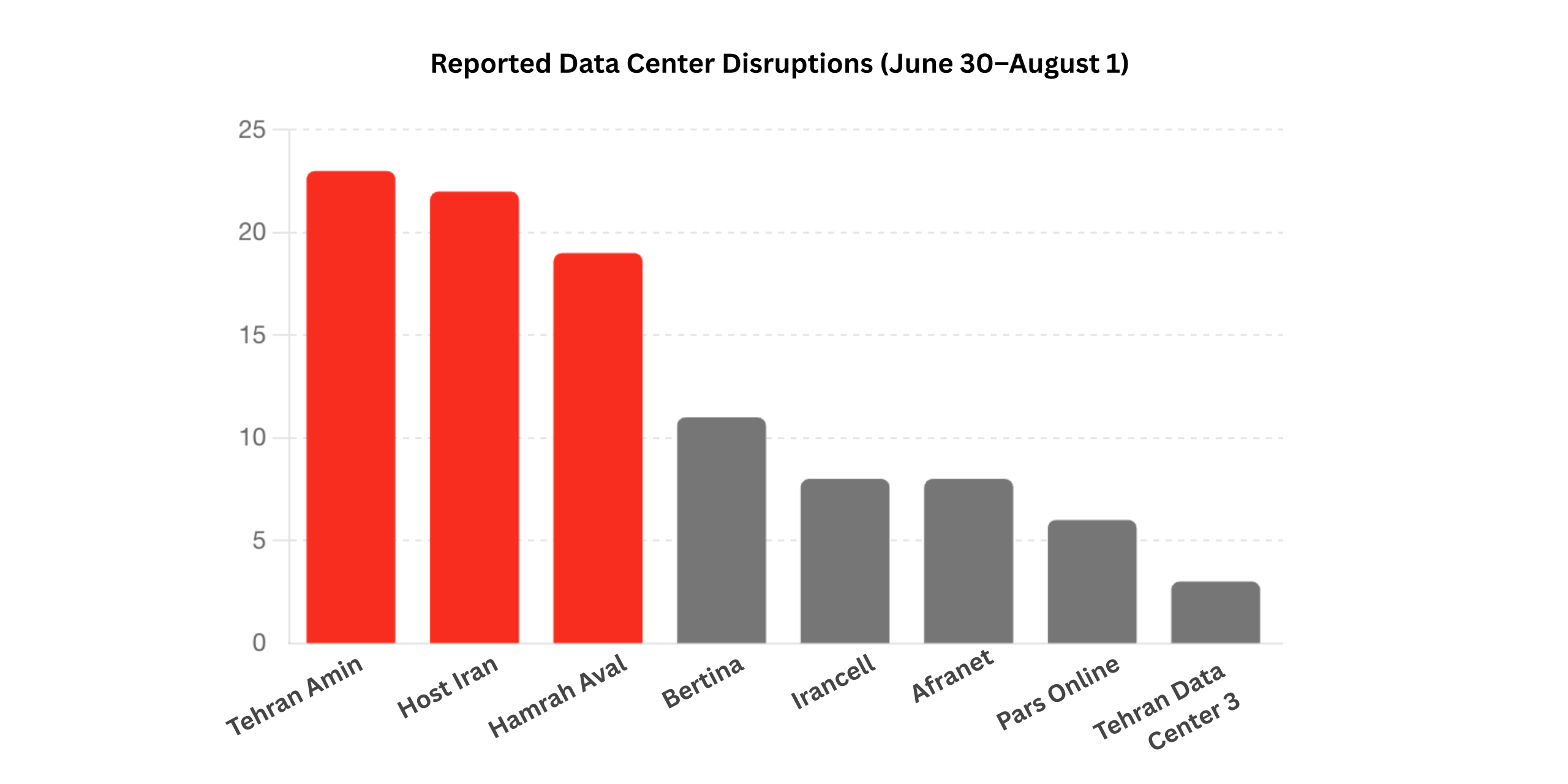

Over the past month, monitoring tools recorded at least 102 significant internet disruptions in Iran. A large number of these were linked to data centers, with two incidents being particularly widespread.

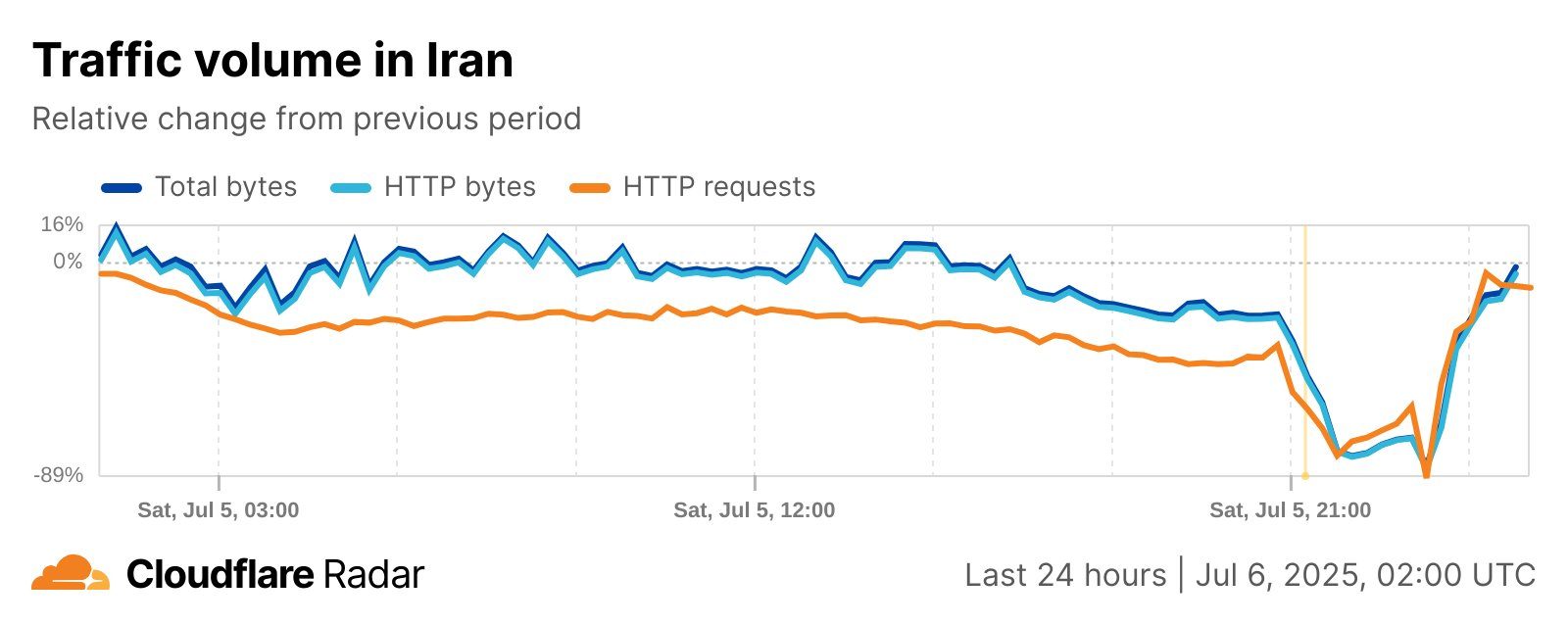

On July 6, Iran experienced a nationwide internet outage from 12:30 AM to 3:30 AM local time. Reports initially came from cities like Dezful and quickly spread to Tehran, central cities, Shiraz, and Rasht. Data centers belonging to Hamrah-e Avval, Afranet, HostIran, Pars Online, and Bertina all experienced severe disruptions during this time. Cloudflare also confirmed an 80% decrease in Iranian internet traffic.

On July 12, the internet was disrupted from 3:30 PM to 5:30 PM local time. According to the internet monitoring website IODA, the BGP index dropped sharply during this period. Behzad Akbari, CEO of the Telecommunication Infrastructure Company, attributed the outage to a widespread fiber optic cable cut outside the country. Extensive disruptions were also recorded on the ArvanCloud radar for data centers like Irancell and HostIran.

In addition to these two major events, the most frequent disruptions were reported on July 4, 5, 13, 14, and 16.

Most of the disruptions occurred between 1:00 AM and 3:00 AM, and again between 3:00 PM and 6:00 PM.

The three data centers with the most reported disruptions were Tehran-Amin, HostIran, and Hamrah-e Avval.

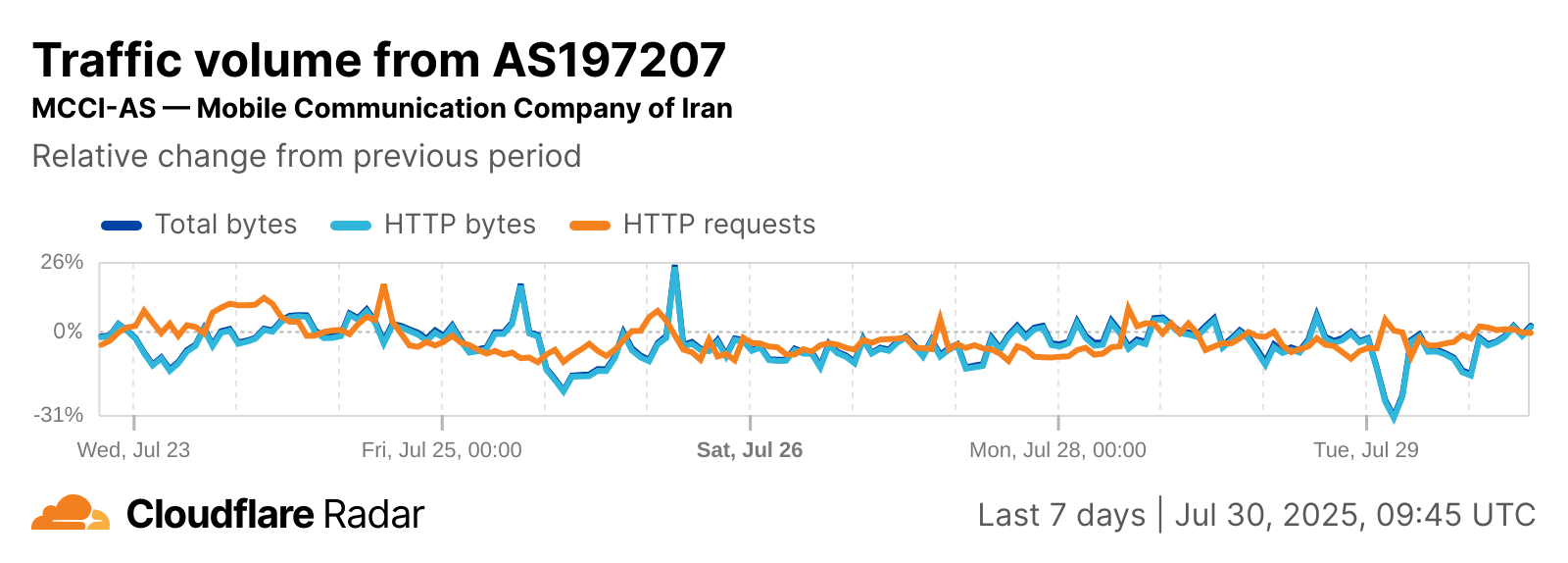

From July 28 to July 30, social media users reported severe, hours-long disruptions to Hamrah-e Avval mobile internet access across various parts of Tehran. Although the company did not respond to these reports, data from Cloudflare confirmed a noticeable drop in HTTP indicators during this period.

- Widespread GPS Disruptions Spark Discussion of Costly Migration to China’s Baidu System

Continued widespread GPS disruptions, even after the recent ceasefire, have intensified the debate about replacing it with China’s Baidu satellite system.

The CEO of Neshan, a navigation platform, described such a migration as “costly.” He noted that because the decision-making authority for this issue is unclear, there is no timeline for when the disruptions might be resolved.

Ehsan Chitsaz, the Deputy Minister of Communications, attributed the “political nature of the disruptions” to the U.S. Department of Defense’s control over GPS. On July 23, he announced that the protocols for implementing Baidu were being finalized.

- Continued Crisis in Fiber Optic Development

A report released by the Iranian Parliament’s Research Center on July 19 revealed a persistent crisis in fiber optic expansion. Despite promises to connect 4 million households annually to fiber optics, only 74,000 actual connections were made during the first nine months of the Seventh Development Plan.

This significant lag, combined with a lack of coordination among operators and weak regulatory oversight, signals a continued crisis in the development of high-speed fixed internet. As a result, digital discrimination for users in different parts of the country is likely to worsen.

- Network Security Weaknesses in Government Agencies

On July 22nd, during a joint meeting between the Vice Presidency for Science and the Ministry of Communications, Hossein Afshin announced that 51% of executive agencies require network security upgrades.

This statement comes despite a massive allocation of 5 trillion tomans to this sector during the “12-Day War.” The ineffectiveness of current cybersecurity policies means that half of the nation’s critical and governmental infrastructure, along with citizens’ personal data, remains vulnerable.

- Google Ads Filtered: A Lifeline Cut for Digital Businesses

During the “12-Day War,” Google Ads was filtered in Iran under the pretext of “countering enemy advertisements” and remains blocked. This action has cut off a vital customer source for thousands of businesses, drastically increasing their customer acquisition costs. A letter from the E-Commerce Association to the Minister of Communications requesting the lifting of this restriction has so far gone unanswered.

- Widespread Disruptions to .ir Domains

On July 14, users reported widespread disruptions in accessing websites with the .ir domain. The Irnic registry, which is responsible for these domains, went offline from approximately 11:00 AM to 12:00 PM.

In an official statement, Irnic attributed the outage to a “system error” in its nameserver (NS) update system.

- Smart TV Disruptions: A Sign of Tech Restrictions

On July 29, users of Snowa and Daewoo smart televisions reported major disruptions with their devices. The Entekhab Group, the parent company, attributed the issue to “incoordination in communication platforms.”

However, it is widely suspected that the cause was the blocking of foreign services, similar to past experiences with Android phones and cloud services. This incident highlights the extreme vulnerability of Iran’s infrastructure to sanctions. The policy of isolation and “localization,” rather than international cooperation, continues to threaten public access to essential updates and digital security.

Review of Internet Policies

A Direct Blow to the Digital Ecosystem

Last month marked a turning point in the escalation of security and regulatory crackdowns on Iranian startups and online businesses.

On July 1, the website Rasmio was taken offline. Rasmio is a business-relationship analytics platform that collects and processes official data from multiple sources, making it easily accessible to the public, businesses, and organizations. On July 7, its managers were arrested and their databases were seized. The incident was sparked by a controversial video on social media that claimed platforms like Rasmio could be used by foreign spy agencies to identify nuclear scientists. This was despite Rasmio’s role being to aggregate publicly available data from official sources. While Rasmio resumed its operations on July 28, the incident sent an alarming message to the startup ecosystem: in the absence of transparent laws, sudden security decisions can completely halt a platform’s activities.

A short time later, on July 15, the online petition platform Karzar was abruptly shut down. The timing of this event, coinciding with the CEO Hamed Bidi’s explicit criticism of internet outages and filtering, fueled speculation of judicial or security pressure.

Even domestic platforms with official licenses were not spared. On July 22, a shutdown order was issued for Aparat Sport, a platform with over 2.5 million users and a license from the Ministry of Culture. This occurred at the same time that officials were speaking about the “necessity of supporting domestic platforms.” The CEO of SabaIdea’s reaction confirmed that the government’s policies are primarily for selection and control.

This trend culminated on July 27th when Hesam Armandehi, the founder of Divar, withdrew his application for the startup’s stock market entry. His decision came after the IRGC Intelligence Organization officially disqualified him. A formal letter from the Tehran Stock Exchange emphasized that Divar’s entry would be contingent on Armandehi’s absence from the board of directors.

In response, the Tehran E-Commerce Association issued a statement protesting the direct involvement of a security agency in the evaluation process. Divar is the latest victim of a pattern that has previously affected companies like Tap30, Digikala, and Cafebazaar.

Policy-Making and “Localization” Plans: A New Framework for Cyberspace

The past month was marked by a series of new initiatives and approvals that signal the government’s serious intent to control and “localize” cyberspace.

Controversial Legislation and Its Aftermath

The judiciary recently proposed a “Bill to Combat the Publication of False News Content in Cyberspace,” which passed an initial stage on June 29 and was sent to parliament on July 21. This bill, which included severe punishments and extensive restrictions, would have required the Ministry of Culture to establish a system to register information on all platforms and publishers, subjecting their activities to greater government scrutiny.

It also would have allowed courts to suspend media accounts, block new user sign-ups, and cut off advertising revenue. Parliament’s own research office warned it would simply add more criminal laws. Although the bill was withdrawn on July 30, many fear its rules could still be enforced unofficially—just as has happened with previous internet control laws.

New Regulations and Committees

- On July 15, the “Regulation for Facilitating the Activities of Digital Economy Businesses” was approved. This regulation grants extensive authority to a special committee, composed of representatives from the three branches of government and security agencies, to “remove obstacles” for digital businesses. Key concerns about this regulation include its lack of transparency (the full text has not been published), the risk of perpetuating discriminatory “tiered internet” policies, and the committee’s broad security powers.

- On July 22, the head of the Information Technology Organization announced that all government services would now be offered exclusively through domestic messaging apps via the “Ghasidak” service. This plan, along with projects like “G-nef” for aggregating location data, enables unprecedented government surveillance. There are no guarantees for user privacy, and data has repeatedly been used as a tool for repression.

- On July 24th, the head of the National Cyberspace Center announced that the “Content Revenue Sharing Document” was in its final stages. Under this document, a portion of operators’ revenue would be transferred to funds overseen by the National Cyberspace Center to be allocated to domestic, pro-government content creators. The VOD Association and many digital platforms believe this plan will lead to corruption and rent-seeking, and it could also result in another increase in internet prices.

The Push for Localization

- The CEO of the Telecommunication Infrastructure Company’s comment on July 15th—that 70-80% of imported servers are “unsafe”—is another sign of the renewed emphasis on “localization” in the IT and communications sector. This claim was met with a sharp reaction from industry activists, who warned that such an approach would lead to increased costs and equipment shortages.

- The push to localize equipment began some time ago with the domestic production of mobile phones and a native operating system. According to a report sent by Abdolnaser Azadbakht, Director General of Equipment at the Ministry of Industry, Mine and Trade, to the head of the Iran Mobile Association on July 26th, mobile phone imports decreased by 12.5% in the last Iranian year, while domestic mobile production grew by 139%.

The implementation of restrictive import policies and the allocation of extra quotas for parts to domestic manufacturers show that the “localization” policy, as emphasized by the Minister of Communications, is being rapidly executed.