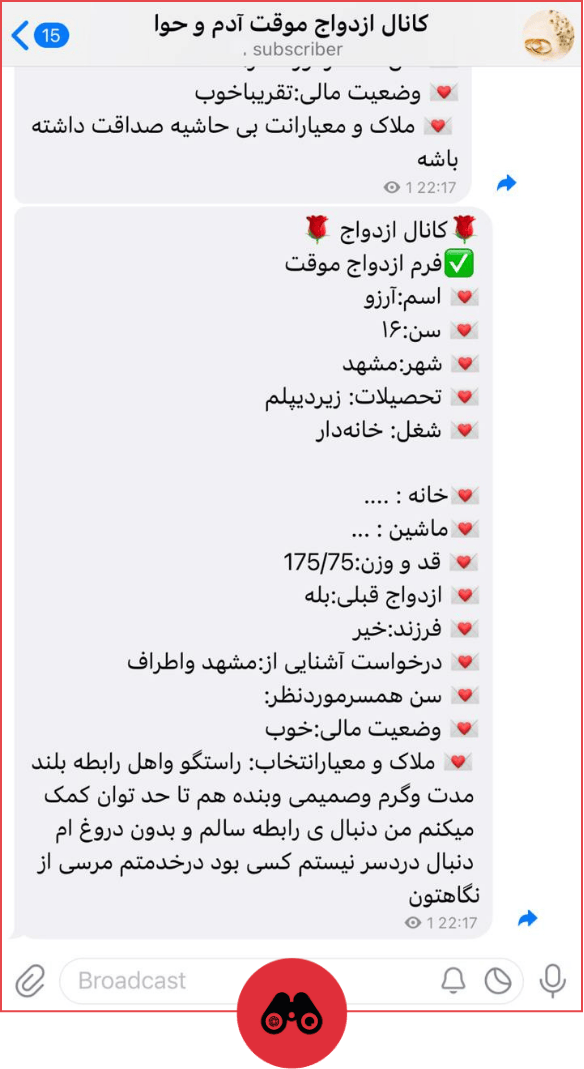

“Spouse-finding” platforms have become a breeding ground for promoting child marriage. Platforms like “Adam va Hava” (i.e., Adam and Eve) and certain channels active on messaging apps like Eitaa and Telegram have long been publishing profiles of applicants under 18, and even under 13 years old. This is a significant shift, as most of these platforms previously required users to be at least 18 years old to create a profile.

It appears that the age restriction for applicants has been removed on at least some of these platforms. For instance, investigations by Filterwatch reveal that nearly 17% of the profiles published on the “Adam va Hava” spouse-finding platform in the last six months belong to individuals under 18 years old.

Child Marriage Advertisements Proliferate on “Spouse-Finding” Platforms

Under the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), every individual is considered a child until they reach the age of 18. Articles 19 and 24 of this very convention obligate governments to protect children from abuse, including early marriage.

Global frameworks for children’s rights include provisions specifically aimed at protecting children online. These include initiatives like “Making the Internet Child-Friendly” and “Blocking Websites with Immoral and Inappropriate Content for Children.” These measures aim to secure the best interests of the child, a concept that has achieved global consensus under the “Parental Control” addendum to the International Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The Islamic Republic of Iran, however, has acceded to the Convention on the Rights of the Child with reservations. According to Article 1401 of the Civil Code, “the marriage of a girl before reaching the full age of 13 solar years and a boy before reaching the full age of 15 solar years is contingent upon the permission of the guardian, provided the expediency [of the marriage] is determined by a competent court.”

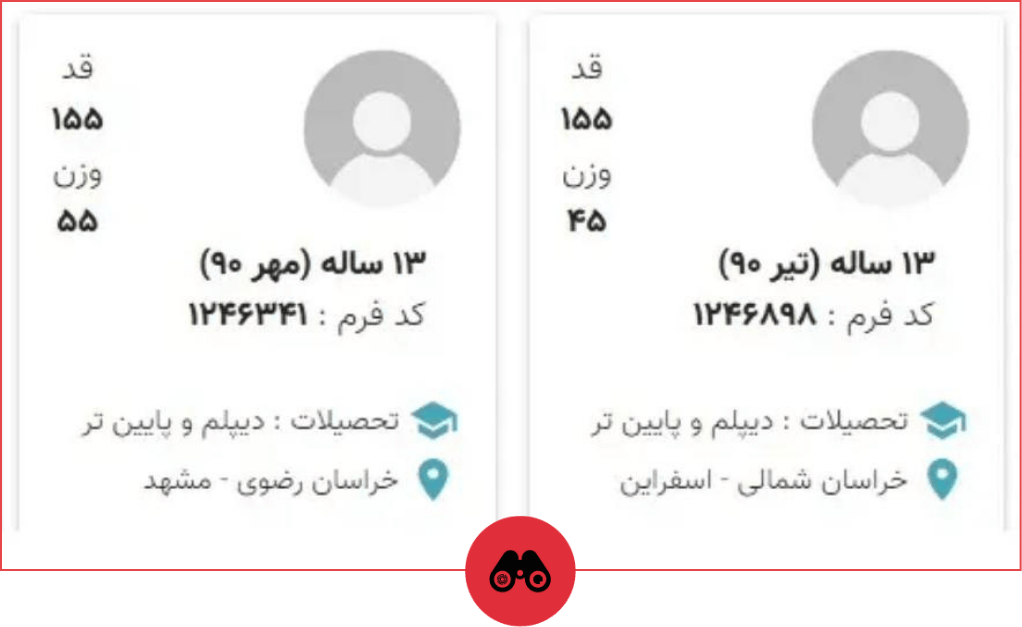

Despite this, the “Adam va Hava” spouse-finding platform publishes profiles attributed to girls as young as 13 years old or even younger.

These platforms also require users to fill out forms with questions that can be considered ideological interrogations. These include inquiries about political leanings, such as the degree of belief in the concept of Velayat-e Faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist). Questions are also posed regarding adherence to religious tenets like prayer, fasting, and commitment to Islamic hijab.

All users on these platforms, regardless of age, must answer all questions related to their political and religious beliefs to register.

Behind the Scenes: Child Marriage Promotion on “Spouse-Finding” Platforms

Some findings by Filterwatch indicate that not all profiles related to child applicants on these platforms are genuine. Certain profiles published on platforms like Adam va Hava or some Eitaa channels are created by their “administrators” to “promote an Islamic-Iranian lifestyle” and lower the age of marriage.

“Maryam Sadri”, who worked as a “facilitator” at the “Adam va Hava Center for Facilitating and Targeting Marriage through Authentic and Traditional Methods” until a few weeks ago, explained to Filterwatch regarding the promotion of child marriage on this platform:

“Many of the posts published on the Adam va Hava website or in Eitaa channels are created by the staff of these platforms or the administrators of these channels to boost the number of visitors with an optimal age for marriage.”

According to Maryam Sadri, starting in July 2023, by direct order of Hossein Asghari, the director of the Adam va Hava Platform, the publication of profiles for individuals under 18 was put on the agenda, framed as “Islamic marriage and an Islamic-Iranian lifestyle.”

Sadri added that subsequently, not only were profiles of children under 18 accepted and published, but even those of girls as young as 13, which is the legal age of marriage for girls in Iran. She further stated that despite internal opposition within the organization, marriage facilitators were instructed to fabricate profiles with these specifications to promote “timely marriage” and artificially inflate the numbers of users in the 15-17 and 13-15 age groups.

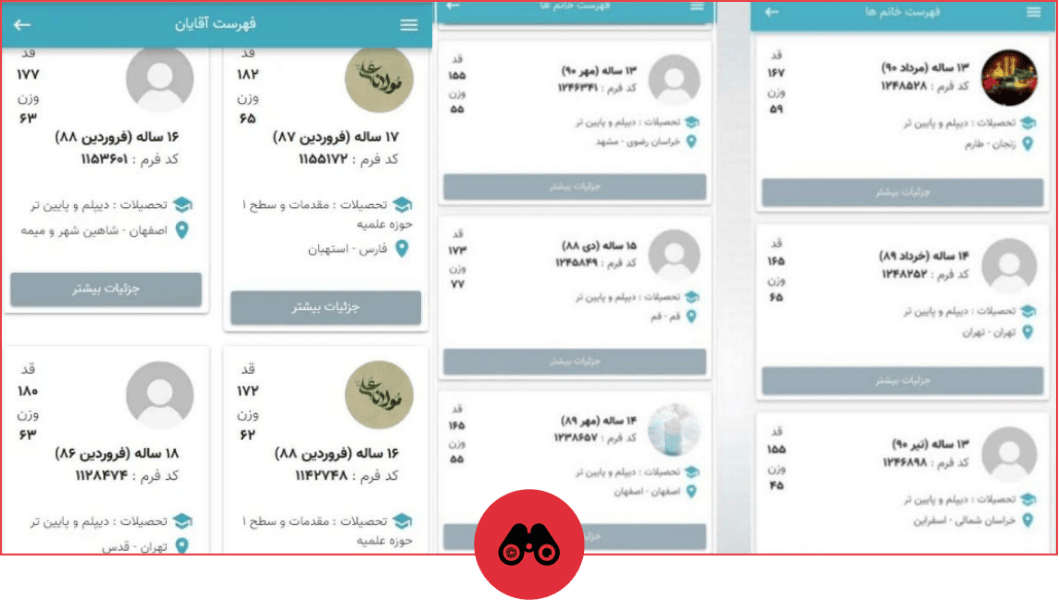

Filterwatch’s investigation reveals concerning statistics regarding underage profiles on these platforms:

- Nearly 17% of published profiles belong to girls under 18 years old.

- The majority of these profiles originate from the cities of Isfahan, Tehran, Razavi Khorasan, Ardabil, Ilam, and South Khorasan.

- Among the registered users, there are also 13 boys under 18 years old: five from Mashhad, two each from Isfahan and Tehran, and one each from Yazd, Borujerd, and Shiraz.

- Approximately 1% of the profiles are for girls aged 13 or 14, with one case as young as 11 years old. Most of these profiles are from Mashhad, Isfahan, Esfarayen, Zanjan, Tarom, and Tehran.

- For users under 18, their educational status is typically listed as “drop-out” or, in some cases, “student.”

It’s important to note that the exact percentage of these profiles created by genuine users versus those fabricated by the platform administrators remains unclear.

“Mohammad Hossein Asghari”, the executive director of the Adam va Hava platform, has addressed the issue of underage users on his platform in an interview with Fars News Agency.

Asghari stated, “The Adam va Hava Platform does not make independent religious rulings; rather, it implements Article 37 of the Youth and Population Law, which sets the legal age of marriage for girls at 13 and for boys at 14. Therefore, we cannot legally prevent girls and boys under the legal age of marriage from completing the forms.”

He further claimed that “all cases involving individuals below the legal age for marriage (15 for boys and 13 for girls) are registered with the knowledge and by the families of these individuals. No form is registered before Adam va Hava staff have spoken with the families, informed them, and verified their eligibility.”

Presenting “Islamic-Sexual” Content Under the Guise of Education

“Spouse-finding” platforms are also providing sexual content, without any warning, under the guise of “educational programs” to all users, including children.

“Spouse-finding” platforms also include sections labeled as “training,” “workshops,” and “lectures” that explicitly address sexual matters, albeit adapted to Islamic values. For example, the Adam va Hava platform features a section called “Dream Bedroom,” while the Hamdam platform (Hamdam is another spouse-finding platform) has a section titled “Intimacy During Engagement.”

Access to these sections is granted to all users, including children who haven’t even registered a profile for spouse-finding on the platform, after paying significant fees.

The access to sexual content by children on these “spouse-finding” platforms stands in stark contrast to the claims made by the Supreme Council of Cyberspace in 2021. At that time, one of the stated justifications for approving the “Document for the Protection of Children and Adolescents in Cyberspace” was precisely to prevent children’s access to sexual content. This very document, which imposes special restrictions on children’s internet access, emphasizes the “classification of all content and services commensurate with age, gender, and physical and cultural characteristics.”

The Islamic Republic has consistently maintained a firm stance against sexual education for children, to the extent that this was one of the reasons for the Supreme Leader’s opposition to UNESCO’s 2030 Agenda.

Yet, under the shadow of these “spouse-finding” platforms, sexual content is being made available to children.

The situation is even more complex on domestic messaging applications like Eitaa, where even the minimal oversight present on other platforms is absent. On Eitaa, there are channels dedicated to temporary marriage (Sigheh), polygamy, and channels containing explicit sexual content.

This proliferation of unrestricted content stands in stark contradiction to recent initiatives aimed at protecting children online. Following the launch of a “children’s internet,” several child-specific SIM cards were introduced to the market, ostensibly to shield children from inappropriate internet content. These include RighTel’s Child SIM card, Hamrah-e Aval’s Anarestan SIM card, and Irancell’s Simba Child and Adolescent service. The common thread among all these child SIM cards is that they disconnect subscribers under eighteen from the general internet network, limiting their access to a specific list of services and content under the pretext of “protecting children’s rights.”

Proponents of internet restrictions, under the banners of “cyberspace purification,” “filtering,” and providing “child internet,” have sought to prevent children’s free access to the internet. These actions, however, directly contradict Article 13 of the International Convention on the Rights of the Child, which explicitly emphasizes “the child’s right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds.”

Therefore, these measures are not only in contradiction with Article 13 but also violate children’s rights by implementing encouraging policies that steer children towards marriage.

Policymaking Serving the Violation of Children’s Rights

Online marriage promotion gained a more official footing in Iran starting in 2021, following the promulgation of the “Youth and Family Population Law.”

Concurrently, the Islamic Republic’s strategic document on cyberspace and the explanatory document for the requirements of the National Information Network fueled the promotion of “early marriage” online. These documents emphasized an Islamic-Iranian identity and lifestyle, with family-centricity as a fundamental value governing the country’s cyberspace strategy. As a direct result of these laws and documents, numerous “spouse-finding” platforms were launched across Iran.

The first online dating blogs and websites emerged in Iran in the late 2000s, including platforms such as “Mercy.com” and “Intelligent Matchmaking System.” However, Tebyan became the first official and licensed “spouse-finding” platform, established in 2015 with the approval of the Ministry of Sports and Youth and Iran’s Cyber Police (FATA). Subsequently, other institutions like Hamdam were gradually founded. Since 2021, and following the promulgation of the Youth and Population Law, there has been a significant increase in the number of these platforms, all operating under the “officially licensed” designation.

Notably, Article 37 of the Youth and Population Law obligates the Ministry of Sports and Youth to issue licenses for “centers active in spouse selection” in cooperation with the Islamic Propagation Organization.

Concurrently, Clause (b) of Article 28 of the same law explicitly prohibits commercial and outdoor advertising in media, including “cyberspace platforms” and “online networks,” that promotes small families (two children or fewer) or singleness. Conversely, advertisers who showcase large families (three children or more) are offered incentives, such as increased airtime.

The subsequent clause of Article 28 assigns the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance the responsibility for monitoring content published online related to “timely marriage” and procreation. Under this law, the Ministry of Culture and Guidance, in cooperation with the National Cyberspace Center, must oversee media and artistic content related to population policies in cyberspace. These two clauses of Article 28 of the Youth and Population Law effectively mean that the Ministry of Guidance, the Supreme Council of Cyberspace, and the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (through the Audiovisual Media Regulatory Organization) are to collaborate in monitoring and controlling content related to marriage, family, and procreation on the internet.

Furthermore, according to the addendum to Article 37 of the “Family Support and Youth Population” Law, the issuance of licenses for “spouse-finding” centers must be carried out in cooperation with the Islamic Propagation Organization and the Ministry of Sports and Youth.

Following the enactment of this law, there was a significant increase in the number of active “spouse-finding” platforms. By early 2025, approximately 205 licensed matchmaking websites or platforms were operating in the country.

Prior to the publication of profiles belonging to underage users on the “Adam va Hava” platform, at least those websites boasting “official licensing” upheld a minimum age requirement of 18 for registration.

To register on any of these platforms, users are required to upload several documents: pages from their birth certificate (personal details and marriage/divorce status), both sides of their national ID card, educational and employment records, military service completion card (for men), and proof of residence (e.g., a utility bill containing a postal code). Given these stringent requirements, none of these platforms can credibly claim ignorance regarding the registration of underage users.

The registration of underage users generates significant revenue for these platforms. According to the Law on Family Support and Youth Population, the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Sports and Youth, the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, the Islamic Propagation Organization, and related bodies are obligated to allocate at least 30% of their financial support for NGOs to programs aimed at reducing the age of marriage, facilitating youth marriage, encouraging procreation, and strengthening families with a religious approach. Based on the budget bill for 2025, this specific line item alone will amount to 180 billion tomans (approximately 3.6 million USD).

Maryam Sadri explained to Filterwatch how this budget is allocated:

“Spouse-finding platforms submit monthly reports to the Ministry of Sports and Youth concerning new registrations, marriages facilitated through the platform, and the age of the applicants.”

According to Sadri, in March 2025 alone, the Adam va Hava platform received 17,000,000,000 tomans (Approximately equivalent to 200,000 USD) based on registrations and marriages within the under-20 and under-15 age groups, justified under the pretexts of “promoting marriage” and “Islamic lifestyle education.”

The violation of children’s rights on “spouse-finding” platforms extends beyond simply allowing underage registrations. In addition to these breaches, from a gender sociology perspective, these platforms also contribute to the reproduction of traditional female roles from a young age, reinforcing restrictive gender patterns in the online sphere.

This perpetuation of gender stereotypes online is mirrored in policymaking and formal education. For instance, the Kowsar Jihadist Task Force – a subsidiary of the Educational Justice and Equal Educational Opportunity Headquarters within Iran’s Ministry of Education – openly focuses on “identity formation and preparing girls for the roles of wife and mother” through cultural, religious, and educational activities. This task force is currently active in 32 provinces across the country.

Since spring 2023, the Civil Registry has refused to provide statistics on child marriage. However, reports published by various media outlets over the past two years, primarily citing the Vice President’s Office for Women and Family Affairs, indicate that Razavi Khorasan, East Azerbaijan, and Sistan and Baluchestan have the highest rates of child marriage.

A review of online “spouse-finding” platforms, however, reveals a striking absence: virtually no applicants from Sistan and Baluchestan province are found on them. This lack of user presence from Sistan and Baluchestan, beyond cultural and traditional factors, may also be attributed to the province’s low internet penetration rate. A report published in 2024 showed that Sistan and Baluchestan ranks worst across all areas, including fixed and mobile broadband penetration.