Amid ongoing power outages and the “Iran-only” accessibility of certain websites and platforms, which have severely limited internet access for citizens, the government has introduced a new “Governed Internet” policy under the guise of “lifting restrictions.”

Governed Internet Instead of Lifting Filtering

*Masoud Pezeshkian, the president who campaigned on the promise of “lifting filtering,” has merged the ideas of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace, the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, and proponents of open internet access into a new proposal for internet accessibility: “Governed and Lawful Internet under the Name of Lifting Filtering.”

Over the past month, all government officials, alongside using the key phrase “lifting filtering” to appease civil society activists, have consistently employed the term “internet governance.” A closer examination of the details reveals that this initiative has little to do with freedom of internet access. This report delves into the specifics of this concept.

While the government and other officials emphasize the necessity of internet governance, Iran’s network continues to experience widespread disruptions. Scheduled power outages, an annual occurrence attributed to “energy imbalance,” have once again led to mobile phone outages in certain regions of the country this year. However, data centers, equipped with backup generators, have faced fewer disruptions.

Since October 2, following Iran’s attack on Israel, Iranian banks have limited their accessibility to an “Iran-Access” network in a bid to prevent DDoS attacks. This restriction remains in place and has led to disruptions in the country’s banking network. Past experiences, such as the year-long internet shutdown in Zahedan on Fridays, and the continued silence from officials on such issues, indicate that this restricted Iran-Access network for banks is likely to remain in place.

The disruption of European connectivity routes has significantly hindered Iranian citizens’ access to the internet. This issue stems from the monopolistic policies of the Islamic Republic regarding internet access, which delegates the provision of internet services exclusively to the Telecommunication Infrastructure Company. Under this centralized approach, the severance of a single route can lead to substantial disruptions in internet functionality.

The Repeated Promise of Lifting Filtering: A Code Name for Governed Internet

In recent days, officials of the Islamic Republic have repeatedly promised the lifting of internet filtering, while effectively advocating for the imposition of governance over cyberspace.

Last month, Pezeshkian emphasized that lifting filtering does not equate to abandoning control over cyberspace. Similarly, the Minister of Communications reiterated a long-standing claim, stating that the unblocking of foreign platforms is conditional upon their compliance with the laws of the Islamic Republic.

The most revealing statement on this topic came from Fatemeh Mohajerani, the government spokesperson. In an interview with the Islamic Republic’s official news agency, IRNA, she claimed that during a session of the Supreme Council, there was a consensus on the need to “lift filtering,” yet no agreement was reached on the manner of its implementation.

The traces of this “lack of agreement” mentioned by Mohajerani can be found in quotes from members of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace published over the past month.

Members of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace have consistently emphasized the necessity of “governing cyberspace.” This culminated on November 12, 2024, when the council approved the formation of a committee within the National Cyberspace Center to deliberate on what Mohammad Amin Aghamiri, the Secretary of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace, referred to as “internet blocking policies.”

Analyzing Governed Internet Instead of Lifting Filtering

On November 4, 2024, a conference titled “Moving Beyond the Openness-Control Dichotomy” was held at the Research Institute for Islamic Culture and Thought, organized by the Cyberspace Studies Center and the Governance Think Tank. The event focused on the ideal vision of the ruling political establishment regarding internet governance. The participation of three prominent figures in internet policymaking in Iran added significance to the discussion.

The attendees included Arash Vakilian, a doctoral candidate in social policy at Baqir al-Olum University; Mohammad Keshvari, an expert in internet accessibility; and Mohammad Ehsan Kharamid, the former head of public relations at the Ministry of Communications.

The conference emphasized that, ideally, filtering should transition into governed internet systems, where users unknowingly operate within the national internet infrastructure and internal platforms. In this scenario, censored content is delivered to Iranian users through simulated shells that filter out “inappropriate” material. The government has previously tested these concepts on a smaller scale through shell program initiatives like Telegram Talaei and pilot projects like “intelligent filtering.”

Moreover, it was stressed that the identity of internet users must always be identifiable to the government, even if they appear to use pseudonyms on social media platforms.

A day after the conference, Arash Vakilian shared a post on the domestic messaging platform Baleh, detailing the government’s envisioned model for a governed internet.

His explanation outlined three main components:

- Social Responsibility in Using Domestic and International Platforms: The idea of user identity transparency was first introduced in 2018 by Abolhassan Firouzabadi, then head of the National Cyberspace Center. He argued that the government should implement such a policy, acknowledging even then that they were behind schedule in its execution.

- Engagement and Negotiation with International Platforms: Efforts to persuade foreign platforms to establish offices in Iran date back to the presidency of Hassan Rouhani. There is evidence of negotiations between Telegram and the Islamic Republic from this period.

- Traffic Management of Domestic and Foreign Platforms: Traffic differentiation between domestic and international platforms began under the Ministry of Mohammad Javad Azari Jahromi, using techniques such as white, black, and gray lists to control speed and disrupt specific sites or platforms. Under Issa Zarepour’s tenure as Minister, this policy escalated significantly: bandwidth for international platforms was reduced, and foreign traffic became several times more expensive, making access to international internet services considerably slower and costlier for Iranian users.

On November 20, 2024, Rasoul Jalili, a member of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace, stated that the public is satisfied with domestic platforms, and there is no need to lift filtering. His remarks sparked strong criticism, particularly from Neshan, a domestic platform, and Mohammad Javad Shokri-Moghaddam, CEO of “Saba Idea”, the parent company of Aparat and Filimo. They argued that Iran’s internet infrastructure, including local platforms, has suffered significant harm due to sanctions and imposed restrictions.

“Governed Internet” as the Unified Voice of Security Institutions

In Iran’s judiciary, from the Chief Justice to the spokesperson, officials have consistently emphasized that cyberspace must be managed. They argue that “internet governance” is a standard practice worldwide. The Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, Ali Khamenei, has reiterated the necessity of curbing a “free-for-all” environment in cyberspace, calling for strict control to ensure its governance.

While most technology and internet-focused media outlets, such as Peyvast, Digiato, Fanzi, and Hammihan, have published content promoting the removal of filtering, Hamshahri Newspaper, known for its alignment with hardliner views, took an opposing stance.

In a report published on November 21, 2024, Hamshahri cited Khamenei’s remarks on the “lawlessness of cyberspace” and the Chief Justice’s advocacy for “internet governance in all countries.” The report presented examples of laws in democratic nations targeting child abuse, animal cruelty, and terrorism, alongside cases of internet shutdowns and restrictions in authoritarian regimes, to argue in favor of Iran’s right to regulate cyberspace.

Despite these justifications, Iran’s history in this regard is telling. The government has a well-documented record of long-term and deliberate internet shutdowns, systematic disruptions, and harsh security measures against users. Critics argue that the push for “governed internet” is not about ensuring order but rather about imposing severe restrictions on internet access, censoring information, and making it easier to identify and target civil activists and ordinary users.

Power Outages Impacting Mobile Networks and Data Centers

Power outages have been a recurring issue in recent years, causing widespread disruptions to citizens’ access to the internet. These disruptions are primarily due to power cuts at data centers and the depletion of backup power for mobile antennas. Last month, it appears that the widespread use of generators and shorter outage durations helped manage these disruptions to some extent. However, mobile antennas continued to cause interruptions in citizens’ access to the internet and mobile services.In response to this issue, Iran’s Communications Regulatory Authority issued a directive on November 20, 2024, requiring mobile operators to maintain and upgrade their equipment to ensure uninterrupted services.

Continuation of Iran-Access for the Banking Network

The Iran-Access restriction on the country’s banking network, which began on October 2, coinciding with Iran’s attack on Israel, remains in place. Reports of disruptions in Bank Mellat’s systems on November 10 and November 21 indicated issues affecting payment systems at fuel stations and the bank’s mobile banking services. Bank Mellat’s public relations office attributed the disruptions to “infrastructural issues” without explicitly mentioning the Iran-Access restriction.

Disruption of European Routes

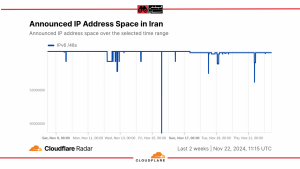

On Thursday, November 14, starting around 12:00 PM local time, major internet providers—Pars Online (AS16322), the Telecommunication Company of Iran (AS58224), Afranet (AS25184), and Respina (AS42337)—experienced severe disruptions, impacting Tehran and at least 10 other provinces. Additionally, sources monitoring filtering reported a 60% reduction in bandwidth during this time, and the IPv6 protocol faced significant disruptions.

Behzad Akbari, CEO of the Telecommunication Infrastructure Company, announced on Twitter that the recent issue was caused by a disruption in the internet supply routes in Europe. Data from filtering monitors, showing a significant drop in transit traffic through Iran’s routes, confirms this claim.