On 13 September 2022, Iran’s so-called “morality police” arrested Mahsa Amini (Jina in Kurdish), a 22 year old Kurdish woman in Tehran for wearing “improper” hijab according to the authorities. Within a few hours, authorities informed Mahsa’s family that she had been taken to a hospital, where she died later the same week.

While authorities denied any wrongdoing, Mahsa’s death sparked a wave of protests across the country, with women at the forefront, calling for accountability for Mahsa’s death and for freedom for women inside Iran. Protests eventually drew in larger crowds, morphing into wider anti-government protests. As protests began to escalate, Iranian authorities followed their usual pattern of crackdown on protests: internet disruptions, censorship, shutdowns, and use of force against protesters.

It is difficult to give accurate figures of arrests and deaths inside Iran during the protests, however, according to a report published by the Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA) on 12 October, at least 200 people have been killed – including 18 children- and an estimated 5,500 people have been arrested though actual figures may be much higher.

As the death toll and arrest numbers continue to rise from a deadly crackdown, we have observed worrying developments around internet restrictions in Iran from the early days of the protests, designed to restrict communication on the ground and to prevent the flow of information into and out of the country. While internet disruptions and censorship during protests is not a new development in Iran, this time the government’s approach is different to the last major protest in November 2019 which saw a near-total nationwide internet shutdown imposed for around a week.

Some of the key developments and observations are detailed below:

Key Events:

- For the first time since the 2009 “Green Movement” protests we are seeing the Iranian government use an aggressive targeted approach to restrict every single channel of communication instead of resorting to the costly option of a total-internet shutdown which was used during the November 2019 protests:

- Authorities blocked WhatsApp and Instagram around 21 September, which were two of the very few international platforms not blocked in Iran, both of which have large numbers of users inside the country.

- Authorities blocked nearly all email providers with the exception of Gmail, iCloud and ProtonMail. Gmail and iCloud are essential for Android and iPhone devices, and Gmail is the most popular email service used by some Iranian officials which could explain why they were not blocked.

- Authorities blocked chat functions on video games. All games with chat functions were either forced to disable their chats in accordance with the order of Iran’s Computer & Video Games Foundation, or they would be blocked. As a result many games including Clash of Clans and Xbox games were blocked.

- Messaging apps such as Viber, IMO, and others were blocked as soon as users moved to use them following the blocking of popular communication platforms such as Instagram and WhatsApp.

- Google Play Store, the Apple App store were also blocked

- All international search engines apart from Google have been blocked

- As those inside Iran scrambled to gain access to remain connected to the international internet, Iranian authorities attempted to block a number of circumvention tools. According to Top10VPN, unsurprisingly, demand for VPNs has surged in Iran following the protests, especially following the blocking of Instagram and WhatsApp, with the demand increasing by 3,082% on 26 September, which was at its highest to date since the start of the protests.

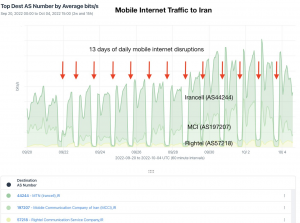

- In contrast to the November 2019 protests, which authorities responded to by implementing a nationwide shutdown, we have not yet observed a total internet shutdown in response to the current protests. Instead, despite around a month of protests, we have only seen localized shutdowns from 21 September until 10 October, targeting protest areas, especially in the evenings. These shutdowns have mostly targeted mobile internet access. On a few occasions during the localized shutdowns, network connectivity was restricted to domestic internet services only via the National Information Network (NIN).

- On 18 September, a major mobile internet provider, Hamrah-e-Aval (MCI) began blocking text messages containing “Mahsa Amini” in Persian, so that the recipients of these texts never received these messages. Keyword censorship has not been widely observed since the 2009 protests.

- We observed severe internet disruptions and total internet shutdowns in the city of Sanandaj in Kurdistan province from 10 October until 11 October. Major protests have been taking place in the city of Sanandaj, with reports of use of lethal force by authorities and heavy crackdowns against protestors.

- An Iranian official revealed facial recognition technology to identify any “failures to observe hijab laws” or unusual “movements” which cross-checks images against government ID databases. Though limited details are available about the type of technology used and the developers behind it, in December 2021 IPVM, a surveillance research group, reported on a contract between Tiandy, a Chinese video surveillance company, and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), police, and the military. Our latest report has more details on how digital services in public spaces in Iran have been used to further the Iranian government’s surveillance efforts to further curtail freedom of expression and erode the privacy of those inside Iran.

- While fixed broadband networks remained mostly connected, they were severely disrupted at times. It should be noted that fixed broadband penetration rates in Iran is less than 20% according to official figures.

- Since the death of Mahsa Amini and the start of protests a month ago, there are now over 274 million tweets with the hashtag Mahsa Amini in Persian according to reports, though exact figures for inauthentic content and users are not currently available.

Timeline of internet shutdowns

As large crowds took to the streets in Mahsa’s hometown of Saqqez, Kurdistan Province on 16 September to mourn and protest her death, authorities cut off access to mobile data and reportedly disrupted access to Instagram and WhatsApp. The order for the internet disruption was issued by Kurdistan’s Provincial Security Council (Persian: شورای تامین استان) — the provincial-level division of the National Security Council chaired by the governor.

On 18 September, a major mobile internet providers, Hamrah-e-Aval (MCI) and Irancell began to block text messages containing “Mahsa Amini” in Persian, so that the recipients of these texts never received these messages. Key word censorship has not been widely observed since the 2009 protests.

On 19 September, as protests began to intensify across Iran, internet shutdowns and disruptions – especially on mobile networks – similarly spread across the country. In some parts internet speeds were throttled, resulting in very low to no connectivity.

Another trend was also observed amid some of the internet disruptions in Iran, as users were given ‘layered’ or ‘tiered’ access to the internet via the National Information Network (NIN). This meant that while individual internet users’ access to the international internet was severed, local data centers, and in turn, local businesses were able to have access to local services via the NIN, which lessened the economic impact of these internet shutdowns, compared to a total internet shutdown, similar to November 2019.

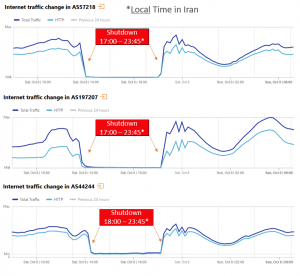

Between 21 September to 4 October, we have been observing a pattern of mobile data shutdown across Iran, usually beginning at around 4pm local time (UTC +3:30) until midnight. The timing of these shutdowns usually coincided with the most active periods for protests and gatherings.

Data provided by Kentik

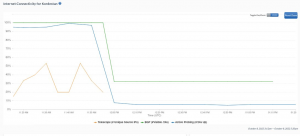

On 8 October a near-total mobile internet shutdown was observed in the western province of Kurdistan – a major site for protests – especially as the crackdown against protests began to intensify, including the use of live ammunition and tear gas, including into people’s homes, according to reports received by Amnesty International. Local services via the NIN were available during this time.

On 9 October, a mobile internet shutdown was observed in Kurdistan once again.

Data provided by CloudFlare

Data provided by CloudFlare

From 10-11 October, a total internet shutdown was implemented in the city of Sanandaj, the provincial capital of Kurdistan, during which even the NIN was not available. During this time, other parts of Kurdistan province were being cut off from international services while remaining connected to local services via the NIN, as a violent crackdown against protests continued in the province.