Over the last few years, we’ve highlighted how President Rouhani and an empowered Supreme Council of Cyberspace (SCC) have together overseen the development of a coherent and dangerous policy agenda that seeks to downgrade Iranians’ digital rights. However, away from the limited transparency of policy papers and regulations, Iran’s Judiciary, Cyber Police (FATA), and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) also play significant roles in threatening citizens’ rights online.

Iran’s new Chief Justice (and Head of the Judiciary) Ebrahim Raisi previously went head-to-head with Rouhani on internet governance issues during the 2017 presidential election. During that campaign, Rouhani avoided proper scrutiny of his ICT policies by appearing as a moderate next to the hardline Raisi. Although Raisi ultimately lost that election, his appointment to the top of Iran’s Judiciary in March 2019 has seen him regain his position on the Supreme Council of Cyberspace (SCC), allowing him to exert his influence over internet governance debates in coordination with FATA and the IRGC.

In this article, we outline our strategy and justifications for stepping up our monitoring of the Judiciary’s interventions into internet governance in Iran. We will argue that the behaviour of Raisi over the last year suggests the reemergence of an interventionist Judiciary, and will explain why this trend merits greater attention and engagement from digital rights defenders.

The Judiciary Before 2013 — Influencers

Over the last few years, Iran’s ICT Ministry and the SCC have emerged as the most influential actors in shaping national ICT policy. In our past publications we have documented how these institutions have been able to reshape the landscape of digital rights in Iran through the development of the National Information Network (NIN).

However, before these two institutions consolidated their control over Iran’s policy-making and censorship apparatus it was the Judiciary that proved to be the most active in implementing a (largely ad-hoc) censorship regime.

Before the passage of the 2009 Cyber Crimes Law (CCL) and the creation of the Committee to Determine Incidences of Criminal Content (CDICC), Judiciary officials in Iran played an influential role in development of the restrictive censorship regime by issuing orders to ISPs to block access to specific websites and blogs. During this period, the Judiciary also made Iran a particularly unsafe place for bloggers and online activists by routinely arresting them on trumped up charges related to national security and morality.

The 2009 Cyber Crimes Law was co-written by Judiciary officials, and contained provisions entrenching the body’s influence over the development of censorship policies. The CDICC was created after the passage of the law, a body hosted by the Judiciary, and granted the power to decide which sites and services should be blocked in the event that they do not comply with Iranian law. The 12-member body has been hosted by the Judiciary since then. As the Judiciary holds the Secretariat of the body, it has been able to set the agenda for its meetings.

The CDICC’s grip over censorship policy was only weakened after the election of President Rouhani and an influx of pro-reform MPs into the Majles after the 2016 parliamentary elections. These elections robbed the Judiciary and its allies of a majority on the body, with government representatives less enthusiastic about blocking websites and services outright. Furthermore, the centralisation of policy-making power in the SCC has robbed the CDICC of some of its influence in shaping policy at the national level.

Although the CDICC appears to be somewhat diminished in influence compared to the early 2010s, it is entirely possible that — with the election of a new principlist-dominated Majles, and the appointment of Judiciary allies to the CDICC — the body will start to exercise its powers once again.

The Judiciary Since 2013 — Judicial Interventions

Even during the period where they lacked a working majority on the CDICC, the Judiciary never ceased to shape digital rights in Iran. Judiciary officials have routinely used their powers to bring forward charges against both well-known and low-profile social and political activists for their online activities, creating an environment of fear and self-censorship. For instance, in April 2017 a Judiciary spokesperson announced that it will bring forward security- and morality-related charges against a number of arrested channel administrators on the messaging app Telegram.

Perhaps the most notable Judiciary intervention in recent years was its imposition of a ban on Telegram on 30 April 2018. Judge Bijan Ghasemzadeh, the Tehran Special Prosecutor’s Officer for Media and Cultural Offences issued the order. The unilateral judicial ruling closed down months of high-profile political and public deliberation around the future of the app, and demonstrated the Judiciary’s power to intervene forcefully in the realm of ICT policy in spite of its comparative marginalisation within formalised policy-making bodies like the SCC.

At the same time as judges like Ghasemzadeh are intervening to exercise the judiciary’s powers over censorship, more senior officials are manoeuvring to exert more influence over longer-term policy discussions — none more so than Chief Justice Ebrahim Raisi.

The Chief Justice — Ebrahim Raisi and His Agenda

At the age of 59, Ebrahim Raisi is one of the youngest officials at the top of Iran’s political establishment. He is also one of the figures with the worst human rights records. Raisi played a central role in directing the mass execution of political prisoners in the late 1980s, sitting on the “death commissions” that sentenced thousands to death. Although he failed to dislodge Rouhani in the 2017 presidential elections, he was nonetheless appointed as Iran’s Chief Justice in March 2019, where he now heads the country’s Judiciary.

Raisi’s record on digital rights and his rhetoric on Internet governance leave no doubt that he remains determined to resist any elements of pluralism or an open society in Iran. As we highlighted at the time, Raisi’s presidential campaign openly sought to impose heavy-handed controls on the internet in Iran. On March 11 2016, while discussing the regulation of Telegram and other social networking sites in his capacity as Attorney General, he stated:

“If we do not control cyberspace, have no doubt that it will threaten society’s way of thinking, its good deeds, its mental state, and its morality. The whole world knows that these networks need to be controlled — sometimes you hear about the UK, or the EU, or some of the Asian countries filtering these networks.

Intelligent filtering is effective, but we must go beyond this. If these networks want to be active in Iran, they should bring their servers inside the country so the Intelligence Ministry can manage them. When you have a highway with no rules, then without a doubt there will be thousands of problems. Now these networks are invading families’ privacy — the complaints that Iran’s Cyber Police (FATA) have to deal with are demonstrations of this.”

Raisi’s appointment as Chief Justice (and thereby as the formal head of the Judiciary) by Iran’s Supreme Leader has meant that he has now returned to the SCC. On the evidence of his first year in-post, it seems apparent that Raisi remains committed to downgrading digital rights in Iran by consolidating his power, and deploying the Judiciary in interventionist ways to influence ICT policy at the national level.

On 22 June 2019, only a few months after his appointment, he released a statement in which he claimed he hopes to use the Internet to establish a “two-way conversation” with the public in order to “hear their thoughts”. He started his statement by saying that the “damage” caused by cyberspace should not deter Iranian officials from using the internet for their strategic goals, and that authorities should respond to this perceived “damage” within the appropriate venues. The implicit meaning of his statement is that the Judiciary (and other bodies) should take a more active role in regulating and policing online spaces in Iran

Although in the statement Raisi did not outline what steps he may be taking in changing the status quo in Iran, but the statement was a clear and public indication that his criticisms of Rouhani’s ICT policies have not been forgotten. One area that disagreements have already surfaced is in the licensing of IPTV and Video-on-Demand services.

On 18 January 2020, Chief Justice Seyyed Ebrahim Raisi signed a notice that was sent to regional Judiciary officers, notifying them that the responsibility for issuing licences and regulations relating to audio and visuals in cyberspace falls to Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), citing commentary provided by the Guardian Council on 1st October 2000, Articles 44 and 175 of the Constitution, and the Supreme Leader’s declaration addressed to the President dated 13 September 2015. IRIB holds a monopoly over domestic TV and radio broadcasting in Iran. Raisi’s notice states that any IPTV and VoD services that are not licensed by the IRIB are to be considered illegal. This is an issue that we have written about in the past, we have highlighted how such a notice is about consolidating the IRIB’s power gibe over online media, and suppressing voices which disagree with its conservative leadership.

Although Rouhani’s government has protested the notice from the Judiciary, This move by Raisi, seeking to directly confront the executive branch on an issue of internet governance is a good indication of the things to come.

There have been other clear indications that the Judiciary is seeking to take a more interventionist approach in proposing and shaping laws under Raisi’s leadership. On 4 February 2020 Javad Javidnia, the Public Prosecutor’s Deputy for Cyberspace Affairs, hosted the first meeting of the “Working Group on Cybercrime and Cyberspace”. The group, which is composed of Judiciary-appointed academics and experts, has been set up to propose regulatory solutions to what the Judiciary perceives to be the current challenges of cyber crime and digital rights in Iran. It is likely that this is the first step by Raisi’s judiciary to propose repressive legislative measures on issues such as data protection and promotion of domestic messaging apps.

Enforcement — FATA and the IRGC

Much to its displeasure, Iran’s Judiciary does not have the requisite level of influence over internet governance in Iran to introduce legislation, policies, and regulations to further limit the online freedom of Iranian citizens, journalists, and activists. However as the examples above demonstrate, through arrest and intimidations by the law enforcement organisations, the Judiciary in Iran has been a significant force in creating the environment of fear and damaging the online security of internet users.

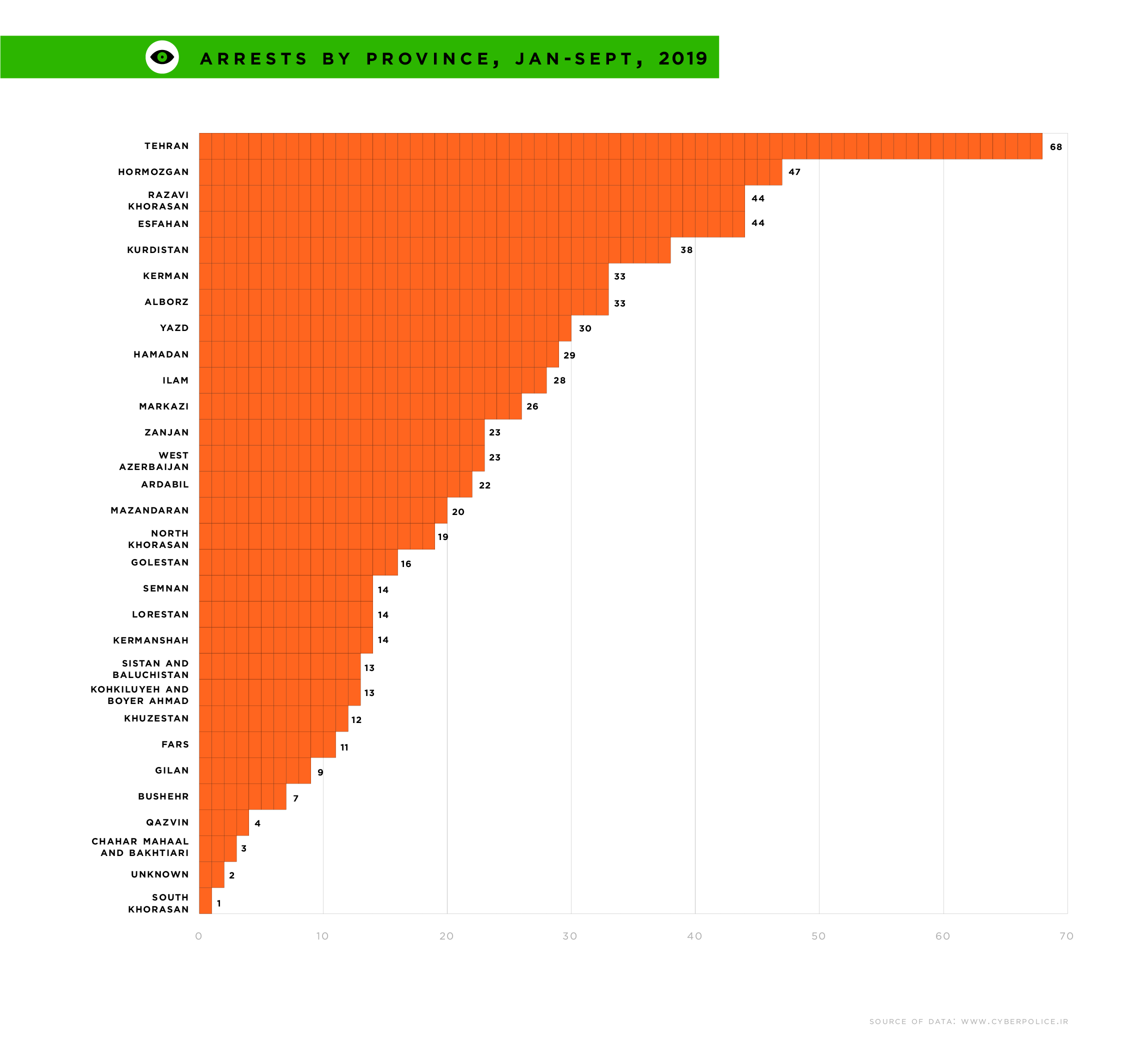

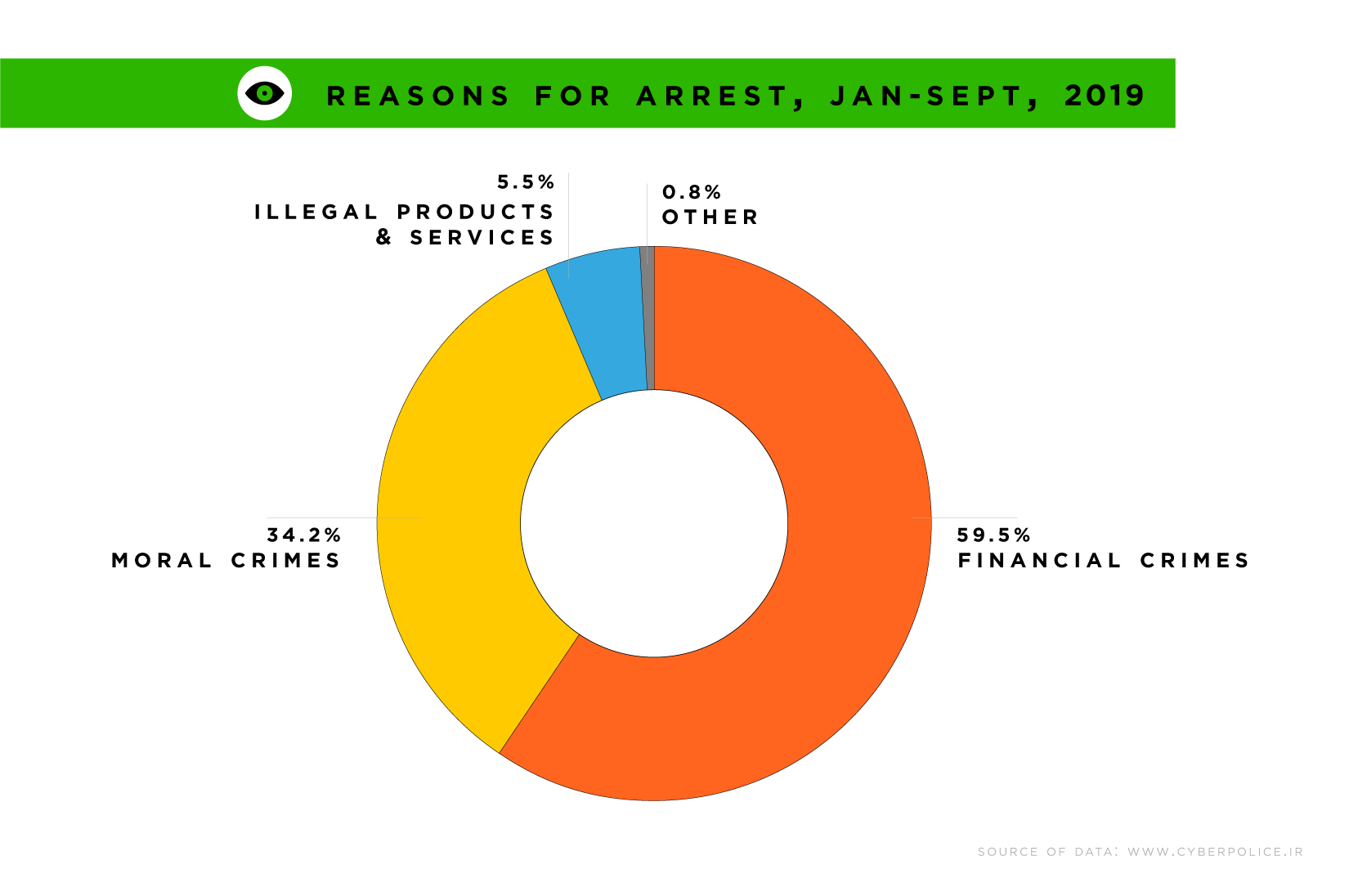

Over the first three quarters of the 2019 we monitored every arrest made by FATA and publicized it on their website. In total we recorded 497 arrests which 208 many of in our assessment were related to moral crime charges.

Similarly, the IRGC has been involved in high profile cases that through invasion of digital privacy have collaborated with the Judiciary. For example in the case of Ruhollah Zam a famous exiled journalist and founder of Amad News, IRGC publicly has claimed that in 2019, lured him out of France and arrested him. Zam is currently on trial at the hands of Iran’s Judiciary.

It is because of the reach and resources of the IRGC and FATA that any small step or vague statement by the Judiciary can lead to a series of arrests and imprisonments, even without any new policies or regulations being formally introduced.

Our Next Steps

Over the last few years we have been focusing on monitoring the policies and protocols that have shaped Iran’s internet infrastructure and the daily use of the internet by the Iranians, and in doing so we have highlighted a number of urgent digital rights threats. However, such an approach also needs to take into account the actions of Iran’s judges and security forces, which have played a major part in the degrading of digital rights in Iran.

The actions of these bodies often place the privacy and security of marginalised groups, activists and journalists at risk. This is why, moving forward we will be publishing regular reports documenting actions of these organisations and the effect that they have on freedom of information and privacy in Iran.

In these quarterly reports we will use the same sources which we formerly used for our FATAwatch reports, as well as the sources that we use for our monthly Policy Monitor reports.

We will also work closely with other human rights organisations with more access to stories of human rights abuses in Iran, to ensure that FATA’s role in enforcing arbitrary detentions does not go unnoticed.

In this way, these reports will demonstrate how Iran’s Judiciary, FATA and IRGC are able to work in tandem to downgrade digital rights in Iran, and expose their activities to much-needed scrutiny.